Excerpt

July 19, 1967

Another long day sloshing around inside that space capsule, gargling my lines through torrents of water spraying in from off camera. It occurs to me that there’s hardly been a scene in this bloody film [“Planet of the Apes“] in which I’ve not been dragged, choked, netted, chased, doused, whipped, poked, shot, gagged, stoned, leaped on, or generally mistreated. As Joe Canutt[son of the legendary Yakima Canutt–Ed.] said, setting up one of the fight shots, “You know, Chuck, I can remember when we used to win these things.”

Editor’s Comments

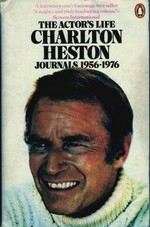

This book has stuck in my head ever since I heard Wallace Shawn (the character, not the actor) say, in the 1981 film “My Dinner with Andre”,

This book has stuck in my head ever since I heard Wallace Shawn (the character, not the actor) say, in the 1981 film “My Dinner with Andre”,

I’m just trying to survive, you know. I mean, I’m just trying to earn a living, just trying to pay my rents and my bills. I mean, uh…ahhh. I live my life, I enjoy staying home with Debby. I’m reading Charlton Heston’s autobiography, and that’s that! I mean, you know, I mean, occasionally maybe Debby and I will step outside, we’ll go to a party or something, and if I can occasionally get my little talent together and write a little play, well then that’s just wonderful. And I mean, I enjoy reading about other little plays that other people have written, and reading the reviews of those plays, and what people said about them, and what people said about what people said, and…. And I mean, I have a list of errands and responsibilities that I keep in a notebook; I enjoy going through the notebook, carrying out the responsibilities, doing the errands, then crossing them off the list!

I just don’t know how anybody could enjoy anything more than I enjoy reading Charlton Heston’s autobiography, or, you know, getting up in the morning and having the cup of cold coffee that’s been waiting for me all night, still there for me to drink in the morning!

If Charlton Heston’s autobiography (or journal, to get picky about it) was worth mentioning in “My Dinner with Andre”, I figured, it must be worth checking out. So when Heston died earlier this year, I decided it was time to give it a try.

By the time he died, Charlton Heston had become a figure it was tough to take a truly objective look at. Although a vocal and visible supporter of civil rights and other liberal causes in the early 1960s, he came out as in favor of Richard Nixon in 1968, and for this and other political stands, especially his stint as president and chairman of the National Rifle Association, Heston got dragged, choked, netted, chased, doused, whipped, poked, shot, gagged, stoned, leaped on, or generally mistreated all the way to his grave. Or, if you were of a different political viewpoint, he got exactly what he deserved.

Whether you agreed with his politics or not, however, credit is due to his body of work as a serious film actor. For some, his seriousness can get a bit relentless at times. Imagine sitting through a marathon of “Ben Hur”, “El Cid”, “The War Lord”, “The Agony and the Ecstacy”, “Khartoum”, “55 Days in Peking”, and “Soylent Green”, just to name a few of his big movies. In all of these and more, Charlton Heston was the archetypal Stoic hero. Heston’s character never trembled in fear, screamed in pain, or whined about his hardships. Hell, he almost never smiled or laughed–a serious man didn’t lighten up. When your Dad told you to, “Be a man!”, this is what he meant.

The Actor’s Life is a generous selection of entries from the journals Heston kept through his most active and successful years as a major star. As he explains in his introduction, Heston began keeping a journal because a yearly agenda book his wife gave him had space at the bottom of each page for a hundred words of diary notes for the day. Heston stuck with these books and this regime for at least twenty years, publishing this collection in 1978, as his career was beginning to wane.

The constraint of space at the bottom of the agenda page gives this book a somewhat odd feeling. There are no long, introspective entries or rambling meditations or verbose descriptions. Rather, this is a collection of 480 pages of life-bites. To be perfectly crude, this is an excellent bathroom book. Just leave a copy by the fixture, catch up on progress toward getting a backer for “The War Lord” or the many Roman dinner parties held during “Ben Hur” or “Agony”. Read about Charlton playing tennis with Rod Laver. Or dining at the White House. Or taking innumerable flights between L.A., London, Rome, or New York–all in first class, of course.

Heston makes no great bones about the trappings of celebrity, of course–it came with the job, in his view. If you enjoy reading about lifestyles of the rich and famous, The Actor’s Life provides plenty of material.

But there is also a wealth of information about all the details and steps involved in getting a movie conceived, produced, and distributed. And about the problems and considerations of acting on film (and on stage–Heston kept up a steady stream of stage work throughout this period). Shooting “The Greatest Story Ever Told” at Cinecitta in Rome, Heston recognizes costumes from “Ben Hur” among the extras. Days are lost on “Hur” thanks to Stephen Boyd’s blue contact lenses (because, as we all know, real Romans had blue eyes). A scriptwriter comes in and makes a hash of things; another (Robert Ardrey) hands in a first draft that proves to be almost verbatim what they end up shooting on “Khartoum”. You learn about some heroic stuntmen, some asinine producers, and, yes, some temperamental actresses.

And you learn that Charlton Heston truly was a serious actor–meaning, an actor serious about his craft, his profession, his technical and artistic skills. The one consistent motif throughout his entries about film-making is his analysis of his own work.He criticizes himself for not achieving the effect he wanted, or for forcing a shot to taken and retaken. He considers what he might have done better. He gives himself credit for getting it right sometimes.

The Actor’s Life could never be considered great literature. A hundred words or so a day cannot lead to art unless you’ve been trained in haiku. But it is a book of undeniable interest and merit if you want to know something about acting, film-making, and life in the public eye. And if you don’t come away from reading it without some measure of respect for Charlton Heston as a man who took his work and his life seriously–well, then I’d have to say that you’re better off sticking with comic books. There are certainly worse role models if you’re trying to “Be a man.”

In Commentary magazine

In Commentary magazine  Bourjaily’s is among the names most often mentioned in the emails I receive from site visitors. Dronamraju covers the two Bourjaily novels I’ve always been most intrigued by:

Bourjaily’s is among the names most often mentioned in the emails I receive from site visitors. Dronamraju covers the two Bourjaily novels I’ve always been most intrigued by:

The title story

The title story  The sculptor Jean Marais paid tribute to this story with a statue that can be found in the Place Marcel Aymé in Montmartre. The statue captures Aymé emerging from the wall just like his character.

The sculptor Jean Marais paid tribute to this story with a statue that can be found in the Place Marcel Aymé in Montmartre. The statue captures Aymé emerging from the wall just like his character.

Gary Smailes invited me to nominate a neglected book for his

Gary Smailes invited me to nominate a neglected book for his