I want to veer off topic for a moment to take note of a remarkable accomplishment that seems to have gone largely without notice.

I’ve been a big fan of audiobooks ever since I discovered they’re a great way to make short work of a long drive. Nowadays, thanks to the convenience of MP3 players, I tend to have one going for workouts and commutes all the time.

When scrolling through Audible’s new releases about a month ago, I was astonished to see listings for William Gaddis’ The Recognitions and JR. I would never have expected to see these titles released as audiobooks. Together, the two books represent nearly 1700 pages of challenging prose. Neither was written with the slightest expectation of ever becoming widely read, and it took Gaddis nearly twenty years after publishing JR to finally gain acceptance as one of the finest American writers of the second half of the 20th century. The Recognitions is a thick book of dense prose telling a story made up of many layers of symbolism and artifice, but it still generally conforms to the structure of a straight-forward narrative.

When scrolling through Audible’s new releases about a month ago, I was astonished to see listings for William Gaddis’ The Recognitions and JR. I would never have expected to see these titles released as audiobooks. Together, the two books represent nearly 1700 pages of challenging prose. Neither was written with the slightest expectation of ever becoming widely read, and it took Gaddis nearly twenty years after publishing JR to finally gain acceptance as one of the finest American writers of the second half of the 20th century. The Recognitions is a thick book of dense prose telling a story made up of many layers of symbolism and artifice, but it still generally conforms to the structure of a straight-forward narrative.

JR, on the other hand, is one continuous tapestry woven of snatches of conversation linked by brief descriptions of landscapes and cityscapes, with almost nothing in the way of landmarks to help the reader find his way through the story. And most of the conversations take place in schools, offices, train stations, restaurants that make the stateroom in the Marx Brothers’ A Night at the Opera seem sedate. Here’s a small sample:

–What’s that?

–The American flag, said Mister Pecci joining them, glittering at the cuff.

–Oh, the film. It’s on film, a resource film on ahm, natural resources, Mister Hyde’s company was kind enough to provide …

–What America is all about, said Hyde, standing away from the set with a proprietary air. –What we have to …

–To use, or rather utilize …

–like the iceberg, rising to a glittering peak above the surface. For like the iceberg, we see only a small fraction of modern industry. Hidden from our eyes is the vast …

–Gibbs? Is that you? Come in, come in.

–No, don’t let me disturb you …

I tried reading JR a few years after it was first published and had to give up short of 100 pages because I just couldn’t make sense of what was happening in the midst of all that chatter. And even though it’s now earned a place in the modern canon by way of publication as a Penguin Modern Classic, it remains one of the most intimidating texts of the last 50 years.

So, from curiosity alone I decided to make it my month’s selection and give it a listen.

Within the first fifteen minutes, I knew that this recording of JR was a work of audiobook narration in a class of its own, a tour-de-force of interpretive skills that represents a real landmark in this medium. Nick Sullivan, the reader, manages to create distinct and convincing voices for the characters in the book’s first scene–the two elderly Bast sisters, one a bit dotty and the other a bit catty, the lawyer Cohen–and to make sense of a collage of dialogue among three people, none of whom is really listening to the others and none of whom manages to finish any of their statements. Then he goes on to tackle a cast of at least ten different characters riccocheting in and out of a principal’s office, including phone calls and in-house televised classes playing on monitors. By the time the book is over, Sullivan has to deal with over 100 (123, to be precise) different characters and easily as many scenes. He manages to be convincing as everyone from an eighty year-old spinster to a twelve year-old boy, as well as lawyers, bankers, brokers, teachers, politicians, low lifes, secretaries, salesmen, artists and ad men.

Within the first fifteen minutes, I knew that this recording of JR was a work of audiobook narration in a class of its own, a tour-de-force of interpretive skills that represents a real landmark in this medium. Nick Sullivan, the reader, manages to create distinct and convincing voices for the characters in the book’s first scene–the two elderly Bast sisters, one a bit dotty and the other a bit catty, the lawyer Cohen–and to make sense of a collage of dialogue among three people, none of whom is really listening to the others and none of whom manages to finish any of their statements. Then he goes on to tackle a cast of at least ten different characters riccocheting in and out of a principal’s office, including phone calls and in-house televised classes playing on monitors. By the time the book is over, Sullivan has to deal with over 100 (123, to be precise) different characters and easily as many scenes. He manages to be convincing as everyone from an eighty year-old spinster to a twelve year-old boy, as well as lawyers, bankers, brokers, teachers, politicians, low lifes, secretaries, salesmen, artists and ad men.

And not only does Sullivan juggle this huge cast and the many abrupt leaps from scene to scene and viewpoint to viewpoint, but he brings out the powerful moods and emotions to be found in JR–the comedy, satire, anger, pathos, and pessimism. JR is a pretty bleak view of the corrupting effect of capitalism, but Gaddis filters that view through a manic style of comedy that operates at times at the speed of an old Fred Allen routine. This is a very funny book, and, at points, a deeply sad and affecting one. What I recalled from reading it as a somewhat incoherent barrage of words proves, through Sullivan’s interpretation, to be a rich and affecting story.

This is the audiobook equivalent of Wilt Chamberlain’s 100-point game. There won’t be another one like this for a long, long time.

I was so impressed by his work that I sent Nick Sullivan a fan email, which he promptly and generously responded to, offering some of his own reflections on the recording of JR and The Recognitions, which he agreed to let me quote for this post:

When I agreed to audition for a couple William Gaddis novels I had never heard of him but the two selections I auditioned with were beautifully written. I “booked” the books… and had no idea of the journey I was about to embark upon. The two books together took me nearly three months to complete.

I have never spent so much time preparing a book. You simply couldn’t record JR without carefully unraveling every scene, determining who was speaking solely by context, verbal tics, and other clues.

I’ll admit that at first I was annoyed at Gaddis for being so willfully obscure … but once I began to record it … well, the man was a genius. A bit of a pessimistic cynic with a dark vision of humanity, perhaps … but a genius. I don’t want to give anything away but I was surprised to find myself choked up a bit in several places. And many was the time I busted out laughing at a particular turn of phrase (usually from Jack Gibbs)….

In some respects Gaddis WAS neglected … at least initially. The Recognitions is an astonishing work as well and received very little consideration until after JR. (so maybe he could be considered a “previously-neglected-author-who-got-his-recogntion”). I’d love to hear his name come up when people talk about “uber-works” from Proust or Joyce.

Out of the 300-plus books I’ve recorded, these two are in a class by themselves. And something fans of Gaddis should know: Gaddis’ writing translates exceptionally well into an audio format.

I have to qualify Nick’s last statement: Gaddis’ writing translates exceptionally well into an audio format when read by a virtuoso.

I realize that audiobooks are not always considered much as media go, but Nick Sullivan’s work on these two polymathic novels deserves a standing ovation from anyone who appreciates the aural and mental pleasure of hearing a piece of fine writing read well. Gaddis’ books are probably still too obscure to gain an Audie nomination for his performances, but I encourage any of my readers who are fans of audiobooks to check out JR or The Recognitions and enjoy two of the finest examples of narrative art ever recorded. Bravo, Mr. Sullivan!

The Hesperus Press, a London-based small press, is celebrating its 10th year in business with a contest in which readers can nominate their candidates for the unknown classic most deserving of reissue.

In early 1934, Malcolm Cowley, then literary editor of

In early 1934, Malcolm Cowley, then literary editor of

BBC Radio 4’s program,

BBC Radio 4’s program,  Like millions of other viewers, my wife and I have been enjoying frequent plunges back into the early 1960s as we blast through the first two seasons of A&E’s “Mad Men” on DVD. I was born in 1958 and have remarkably strong memories from that period: the cars, kitchens, and clothes, in particular.

Like millions of other viewers, my wife and I have been enjoying frequent plunges back into the early 1960s as we blast through the first two seasons of A&E’s “Mad Men” on DVD. I was born in 1958 and have remarkably strong memories from that period: the cars, kitchens, and clothes, in particular.

Technically, this is a novel about getting ahead in the newspaper business, but it is set on Madison Avenue. Its hero, Henry Cade, decides that, “… you could no more want a little success than you could want a little love … To want less than everything was to get nothing.” “Mad Men”‘s Peter Campbell appears to share this philosophy.

Technically, this is a novel about getting ahead in the newspaper business, but it is set on Madison Avenue. Its hero, Henry Cade, decides that, “… you could no more want a little success than you could want a little love … To want less than everything was to get nothing.” “Mad Men”‘s Peter Campbell appears to share this philosophy.

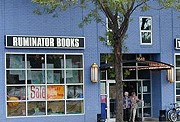

The story of Hungry Mind/Ruminator Books is a parable of how far a passion for books can take you … until simple economics kick in. David Unowsky, who founded his independent bookstore, Hungry Mind Books, near the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1970, and it acquired a reputation as one of a handful of truly great American bookstores. In the mid-1990s, he and his wife, Pearl Kilbride, along with other partners, started up an independent press, also known as Hungry Minds Books. Over the course of its nearly ten years’ existence, the press published 50 titles, with an emphasis on literary fiction, nonfiction and poetry, including a series of reissues of quality non-fiction under the rubrics of Hungry Mind Finds and Ruminator Finds.

The story of Hungry Mind/Ruminator Books is a parable of how far a passion for books can take you … until simple economics kick in. David Unowsky, who founded his independent bookstore, Hungry Mind Books, near the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1970, and it acquired a reputation as one of a handful of truly great American bookstores. In the mid-1990s, he and his wife, Pearl Kilbride, along with other partners, started up an independent press, also known as Hungry Minds Books. Over the course of its nearly ten years’ existence, the press published 50 titles, with an emphasis on literary fiction, nonfiction and poetry, including a series of reissues of quality non-fiction under the rubrics of Hungry Mind Finds and Ruminator Finds. Morley Callaghan is my favorite 20th-century novelist. His

Morley Callaghan is my favorite 20th-century novelist. His  Published in 2007,

Published in 2007,