I flew back to Seattle this week to help settle my father’s affairs. Sorting through his books I kept an eye out for anything out of the ordinary but didn’t find much. When I was a kid, the mainstays of the living room bookshelves were titles from the Book of the Month Club. There were a few exceptions, most notably several Grove Press hardback editions of Henry Miller–the Tropics and Black Spring, which were probably considered hot stuff and discussed with arched eyebrows in the mess.

Then I happened to glance up at the cookbooks over the fridge and spotted the distinctive metallic gold spines of Herter’s Bull Cook books and knew I’d struck gold (pardon the pun).

books and knew I’d struck gold (pardon the pun).

My dad went through a big huntin’ and fishin’ period in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and one thing you could always find in the reading basket next to his chair was a copy of the latest Herter’s catalog.Herter’s was a big mail-order hunting and fishing goods store in Minnesota, and every single item in the catalog had some hyperbolic write-up. There was something of a formula to these things. First there would be some dismissive mention of popular assumptions (“Carborundum is widely believed to be the finest material for sharpening the blade of a knife”). Then this notion would be tossed aside as poppycock in favor of some alternate theory that was far-fetched on average and downright absurd on occasion (“In truth, you will find no sharper edge than can be obtained from vigorous application of duck fat”). I’m making these examples up, but I’m really not far off the mark. Finally, there would be the pitch to convince you that buying an 8 oz. tin of Herter’s rendered duck fat was not merely the smartest choice you could make but the least that could be expected to demonstrate your fitness to remain walking the streets instead of bouncing off the walls of some rubber room.

Herter’s also sold a few books in the catalog, and somewhere along the way my Dad ordered two volumes of their most famous title: Bull Cook and Authentic Historical Recipes and Practices (Volume Two added the subtitle, “Plus Famous Restaurants and Night Clubs of the World”).

(Volume Two added the subtitle, “Plus Famous Restaurants and Night Clubs of the World”).

These were not at all like my mom’s cookbooks. These were cookbooks written for men by a guy without a shred of doubt about his studliness. What cookbook written by a woman would put “Meat” at the front, on the very first page? And lead off with, “How to Make Real Corned Venison, Antelope, Moose, Bear and Beef”? The last is just a concession to the little ladies, I’m sure. The author, George Leonard Herter, provides a short preface explaining the public service he is about to perform:

These were not at all like my mom’s cookbooks. These were cookbooks written for men by a guy without a shred of doubt about his studliness. What cookbook written by a woman would put “Meat” at the front, on the very first page? And lead off with, “How to Make Real Corned Venison, Antelope, Moose, Bear and Beef”? The last is just a concession to the little ladies, I’m sure. The author, George Leonard Herter, provides a short preface explaining the public service he is about to perform:

I am putting down some of these recipes that you will not find in cook books plus many other historical recipes. Each recipe here is a real cooking secret. I am also publishing for the first time authentic historical recipes of great importance.

For your convenience, I will start with meats, fish, eggs, soup and sauces, sandwiches, vegetables, the art of French frying, desserts, how to dress game, how to properly sharpen a knife, how to make wines and beer, what to do in case of hydrogen or cobalt bomb attack. Keeping as much in alphabetical order as possible.

I know I for one am relieved that someone finally thought to include nuclear attack survival tips just after the recipes for Prunes Maxim’s and “How to Make Puff Pastry or Flaky Pastry Dough.”

For the record, the first tip for surviving an attack is to “Get in any kind of cave, ditch, or valley as far away from buildings as you can and lie on the ground face down.” In case you missed the point, Herter adds, “If at all possible get in a cave.” Staying in your house means “the water pipes will burst and flood the basement drowning you like rats in a trap.” So find that cave–got it?

Helpfully, two pages before the list of H-bomb tips is a short article on the “Norwegian Method of Getting Rid of Rats.” The recipe? Simple and lethal–plain white bread, spread with lye, then topped with syrup. Just make sure the kids know not to confuse it with French toast. Serves 4-6.

A few readers will recognize this oddball classic, a genuine “pure product of America,” as Fitzgerald would put it. Among the cognoscenti, George Leonard Herter is treasured as one of the great American nutcases of all time, a man who never let nonsense like facts or objective sources tarnish the immaculate lunacy of his notions.

And who managed to turn his ravings into a fairly profitable business, at least for a couple of decades or more. Herter’s catalog copy went from three-ring binders passed from hand to hand in the early 1960s to editions of 3-400,000 copies by the time my dad got into them. And the Bull Cook went through something like fifteen editions between 1960 and 1970. The little business George Herter started in 1937 was on a par with L. L. Bean (which also, somewhere back in the dark ages, was mostly a supplier for hunters and fishermen) before the whole thing went bust in 1981 and Herter was forced to file for bankruptcy.

Recall that Herter promised to keep things in these cookbooks “as much in alphabetical order as possible.” It doesn’t take more than a few pages of the Bull Cook to make it clear that Herter’s sense of order is on a par with Joyce’s ability to tell a story in straightforward manner. Had Herter lived about 200 years earlier, he might have produced Tristram Shandy ahead of Sterne.

By the way, to pop back to nuclear holocaust for a sec, make sure to note the item on page 337 explaining that, “Red Pepper Good for Radiation and Upset Stomach.”

“Everything you know is wrong”, declared the Firesign Theatre on an early album. Their inspiration was, of course, George Leonard Herter:

- • Never Use Charcoal for Broiling

- The “fumes given off as the briquets burn are extremely toxic.” The right answer: hard coal. “The use of hard coal instead of charcoal in Minnesota for broiling has always been the accepted practice.” Which is why, of course, Minnesota ranks #1 among the states for fine restaurants.

- • A real old buck past the sexual urge stage makes the best eating venison

- However, Herter does admit that, “I have never known an Indian who would not trade ten times the weight in deer meat for either beef or pork or for that matter, although this may seem strange to you, dog meat, which is also good meat.” And you thought they were pets. Bonehead!

- • Avonnaise–“the only new sauce invented since mayonnaise was invented”

- You take mayonnaise and mash it up with an avocado. You should use it on “fruit salads, lettuce salads, and on baked potatoes instead of sour cream sauce, on roast beef instead of gracy or Bernaise sauce, on hamburgers use lettuce, pickles, and avonnaise.” It “was invented by famed Belgian cook, Berthe E. Gramme.” “Once you have tried this sauce you will be using it often.” You may now invent your excuses for not knowing this.

- • The Swedish Method of Preparing Rutabagas is “the only correct way ever invented to prepare them”

- Mash two thirds boiled rutabagas with one third boiled potatoes. “Served in this manner they are one of the finest vegetables you can serve with any meal.” And how have you been fixing them? In shoestring fries, I suppose. Sad.

If one volume of Herter’s ramblings on food is not enough, you need to locate volume two, which weighs in at over 750 pages and includes meditations on restaurants throughout the world and anecdotes of world history I’ll bet you’ll never find in any textbook. Herter sticks to his proven formula. The first page is, of course, “Meats.” This time, however, he adds a half-page grayscale of the Toulouse-Lautrec painting, “Two Friends”.

Herter misnames the painting as “Friendship,” then adds a sly comment that, “The name of this painting is probably one of the greatest understatements ever made.”

You fellas all get it, right?

This to introduce “Toulouse Lautrec Chicken,” which Herter claims was something ol’ Henri often pined for. I won’t bother to summarize it: the fact that it involves a chicken breast cooked for one and a half hours, one quarter pound hamburger, and six strips of bacon is enough to suggest that we’re not exactly in Eric Ripert territory.

Yet a thousand-plus pages on food did not begin to exhaust George Leonard Herter’s capacity for airing his crazy ideas. There are at least five other Herter books to be found, including such irresistable titles as Herter’s Professional Course in the Science of Modern Taxidermy (which failed to spark a wave of D-I-Y critter stuffing); Secret Fresh and Salt Water Fishing Tricks of the World’s Fifty Best Professional Fishermen Plus the Professional Secrets of Fishing Rods and How Fishing Rods Are Made (Revised Fourth Edition)

(which failed to spark a wave of D-I-Y critter stuffing); Secret Fresh and Salt Water Fishing Tricks of the World’s Fifty Best Professional Fishermen Plus the Professional Secrets of Fishing Rods and How Fishing Rods Are Made (Revised Fourth Edition) ; How to Get Out of the Rat Race and Live on $10 a Month

; How to Get Out of the Rat Race and Live on $10 a Month (move to Alaska; zap fish with car batteries or bags of quicklime); George the Housewife

(move to Alaska; zap fish with car batteries or bags of quicklime); George the Housewife (with such handy tips as, “Be Careful to Avoid Touching Synthetic Cothing with a Gasoline Lantern”); and the ode to marital bliss, How to Live with a Bitch

(with such handy tips as, “Be Careful to Avoid Touching Synthetic Cothing with a Gasoline Lantern”); and the ode to marital bliss, How to Live with a Bitch . Although his catalog business went bust in 1981, he kept beavering away for over ten more years, mostly inventing inventions such as a Rube Goldberg-esque process for refining petroleum, before hitting his last carriage return in 1994.

. Although his catalog business went bust in 1981, he kept beavering away for over ten more years, mostly inventing inventions such as a Rube Goldberg-esque process for refining petroleum, before hitting his last carriage return in 1994.

Paul Collins brought Herter’s work back into the spotlight in late 2008 with a fond tribute to “The Oddball Know-It-All” in the New York Times. But don’t settle for second-hand Herter. Get the pure product in all its insanity, uncut and unashamed:

IF YOU TAKE TRANQUILIZERS OR SEDATIVES BE CAREFUL OF THE KINDS OF CHEESE THAT YOU EAT. THE WRONG KIND OF CHEESE CAN KILL YOU. Bull Cook and Authentic Historical Recipes and Practices, volume two, page 733

You’ll thank me when the Big One drops.

Bull Cook and Authentic Historical Recipes and Practices, by George Leonard Herter and Berthe E. Herter

Waseca, Minnesota: Herter’s, 1960

dreamed about Bokhara, a fabulous city that was then more difficult to access than Tibet. I opened my eyes upon the end of not only the nineteenth century but of a second Puritan age. An epoch passed away while I was learning to speak and walk. Its influence remains as the start of memory and as a measuring rod for progress that even Edwardian survivors lack.

I couldn’t resist starting in with the most ridiculous title in the bunch:

I couldn’t resist starting in with the most ridiculous title in the bunch:  Donald Schon’s

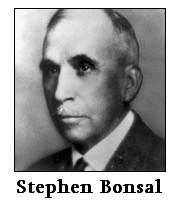

Donald Schon’s  Being selected for the Pulitzer Prize is no guarantee of that anyone will remember your work–at least not more than ten years afterward. Take

Being selected for the Pulitzer Prize is no guarantee of that anyone will remember your work–at least not more than ten years afterward. Take  Bonsal’s book opens on the eve of the Armistice and ends a little over a year later, with the Senate’s rejection of the Treaty. He worked alongside House, and later Wilson, through the preparations and initial sessions of the Conference. A veteran foreign correspondent fluent in a number of European tongues, he acted as an emissary to many of the other delegations and as a personal advisor to House and Wilson. He remained at the negotiating tables throughout most of the Conference, taking only a break of a few weeks to accompany South African General Jan Christian Smuts on a mission to Austria, Hungary, and Serbia in March and April 1919.

Bonsal’s book opens on the eve of the Armistice and ends a little over a year later, with the Senate’s rejection of the Treaty. He worked alongside House, and later Wilson, through the preparations and initial sessions of the Conference. A veteran foreign correspondent fluent in a number of European tongues, he acted as an emissary to many of the other delegations and as a personal advisor to House and Wilson. He remained at the negotiating tables throughout most of the Conference, taking only a break of a few weeks to accompany South African General Jan Christian Smuts on a mission to Austria, Hungary, and Serbia in March and April 1919. I think it was in the long-gone Filippi’s Books in Seattle that I came across the

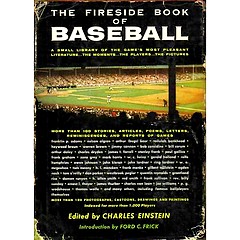

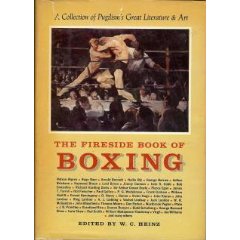

I think it was in the long-gone Filippi’s Books in Seattle that I came across the  Simon and Schuster published at least seven other Fireside books on sports and games, including:

Simon and Schuster published at least seven other Fireside books on sports and games, including: These were not at all like my mom’s cookbooks. These were cookbooks written for men by a guy without a shred of doubt about his studliness. What cookbook written by a woman would put “Meat” at the front, on the very first page? And lead off with, “How to Make Real Corned Venison, Antelope, Moose, Bear and Beef”? The last is just a concession to the little ladies, I’m sure. The author,

These were not at all like my mom’s cookbooks. These were cookbooks written for men by a guy without a shred of doubt about his studliness. What cookbook written by a woman would put “Meat” at the front, on the very first page? And lead off with, “How to Make Real Corned Venison, Antelope, Moose, Bear and Beef”? The last is just a concession to the little ladies, I’m sure. The author,

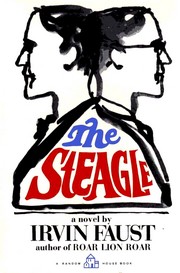

“Opening this book is like clicking on a switch: at once we hear the electric hum of talent,” Stanley Kauffmann wrote in his New Republic review of Irvin Faust’s first book of fiction,

“Opening this book is like clicking on a switch: at once we hear the electric hum of talent,” Stanley Kauffmann wrote in his New Republic review of Irvin Faust’s first book of fiction,  As he told Don Swaim in a 1985 interview (available on the

As he told Don Swaim in a 1985 interview (available on the  In the title story of

In the title story of  It pains me to start 2010 with two pans in a row, but few books have disappointed me as much as Vance Bourjaily’s little-known 1986 novel,

It pains me to start 2010 with two pans in a row, but few books have disappointed me as much as Vance Bourjaily’s little-known 1986 novel,  The last shows that Walton’s kept a discriminating filter on her list. Of Steig Larson’s novels, which someone nominated, she writes, “These are a stupendously successful non-genre best sellers. The opposite of obscure.” I’ve seen them on the end caps of airport bookstores in Belgium, Spain, the U.K., and the U.S. in the last two months: definitely NOT neglected.

The last shows that Walton’s kept a discriminating filter on her list. Of Steig Larson’s novels, which someone nominated, she writes, “These are a stupendously successful non-genre best sellers. The opposite of obscure.” I’ve seen them on the end caps of airport bookstores in Belgium, Spain, the U.K., and the U.S. in the last two months: definitely NOT neglected.

Although he began by calling the book “one of his [Bromfield’s] most remarkable achievements,” after devoting about four times as much text to a recap of the novel’s plot with only an occasional dig, Wilson then dismissed it as, “a small masterpiece of pointlessness and banality.”

Although he began by calling the book “one of his [Bromfield’s] most remarkable achievements,” after devoting about four times as much text to a recap of the novel’s plot with only an occasional dig, Wilson then dismissed it as, “a small masterpiece of pointlessness and banality.”