When he was a young man with aspirations to become a writer, William Saroyan set himself a daily task to write for at least an hour and produce at least a few pages, no matter how good, bad, or irrelevant the results. It established a discipline that served him well for over fifty years, helping produce dozens of books and plays and over a hundred short stories. It also, unfortunately, established a habit of writing whatever came to mind and calling it work. As Bob Secter wrote in his Los Angeles Times obituary, Saroyan approached writing and life in the same way–“spontaneously, impetuously and sometimes sloppily.”

When he was a young man with aspirations to become a writer, William Saroyan set himself a daily task to write for at least an hour and produce at least a few pages, no matter how good, bad, or irrelevant the results. It established a discipline that served him well for over fifty years, helping produce dozens of books and plays and over a hundred short stories. It also, unfortunately, established a habit of writing whatever came to mind and calling it work. As Bob Secter wrote in his Los Angeles Times obituary, Saroyan approached writing and life in the same way–“spontaneously, impetuously and sometimes sloppily.”

As the decades past, this led to an increasing tendency of Saroyan’s writing to read like a random walk through his thoughts, particularly as his output shifted from fiction to autobiography. Between 1962 and 1978, he published ten books that were either memoirs or journals or a combination of both. A constant theme through many of them was death–the death of family and friends, and the approach of his own death (viz. Not Dying (1963)).

So it was not entirely unexpected that he would decide, in early 1977, to set death as the subject for his daily writing assignment. Specifically, he chose the “Necrology” list in the January 5, 1977 issue of Variety for his inspiration:

I am a subscriber to a weekly paper called Variety. The 71st Anniversary Edition, dated January 5, 1977, arrived a few days ago, and I examined with fascination–on the last page, 164–the names in alphabetical order in the annual feature entitled Necrology. I had predicted that among those listed would be 34 men or women that I had met. I was not far off the mark: there were 28. But many of the 200 or more others listed were of course people I knew about, for Variety is the paper, the Bible, as they say, of show business, celebrated in song by Irving Berlin. Well, I thought, I’m very well along into my 68th year, hadn’t I better write about the people I know in Variety’s Necrology of 1976? So that is what I am doing.

Saroyan proceeded to produce 135 pieces, each about 2-3 pages long, running through the list from Alessandro (Victor) to Zukor (Adolph). Names he recognized and those of acquaintances fortunately outnumbered those he didn’t know, but fairly often he had to admit ignorance and plow on regardless, hoping his thoughts might lead somewhere interesting:

The first name on the list is Victor Alessandro, but I never had the honor. I never met him, never saw him, and therefore cannot say anything about him that might be possible had I met him. What might that have been? Well, the fact of him, the reality of him, the reality of the substance of him, or if you choose the myth, his appearance, his face, his voice, his eyes, and anything else that was there.

In this case, it was a false hope. Saroyan wanders off into the thickets, stumbles across a memory that he was in the Army when Stalin met with Churchill and Roosevelt at Yalta, speculates “Perhaps everybody is everybody, no matter who,” and ends by noting, “The third name is Geza Anda, a fine name for a fine variety of reasons, but I have no idea who Geza Anda was, male or female, actor, clown, or what.”

Remembering Saroyan in a 2008 article in the San Francisco Chronicle, his long-time friend, the novelist Herbert Gold wrote of Obituaries:

For me, three short pages, Chapter 106 … the rhythm, sly humor and shrugged-off grief, the sad recapitulation of the pleasures of simple existence, the exalted awareness of mortality, an offhand but measured conviction of moral responsibility are a peak of Saroyan’s long meditation on the sense and responsibility of life. These three pages, which I’ve sometimes read aloud to would-be writers, remind me of “Euthyphro,” Plato’s dialogue on the responsibility of fathers and sons – but with Saroyan’s unique, wise-ass sideswipes at the whole deal. “Reader, take my advice, don’t die, just don’t die, that’s all, it doesn’t pay.”

It’s worth excerpting the closing passage of Chapter 106 to give a sense of just what Gold meant:

And then Johnny Mercer died, and I know him. I knew Johnny Mercer, I saw him sometimes at parties in Hollywood, and sometimes at Stanley Rose’s bookstore, and sometimes at various other places. He wrote the lyrics, the words, to many great songs, but he also sang those songs, and he sang them well. He made good money, but his father died broke and in debt, somewhere in the South, possibly in Atlanta, and quietly Johnny Mercer went to work and paid every one of his father’s debts, even though legally he was in no way obliged to do so, it was a simple matter of pride, of a son not wanting his father to have left anybody holding the bag, and once at a party I told him that I thought he was one of the great writers of words for songs, one of the really good singers of songs, but I had lately heard about what he had done for his father, and that was the thing I now admired about him above all other things, and I was glad that he had not been able to suppress the news of his devotion to his father, and to his own sense of family, as he had wanted to do, for it is necessary for all of us to hear about such news, and Johnny Mercer in his shy way smiled and thanked me, and we talked about the stuff people always talk about at parties, especially Hollywood parties, and that stuff is never without its comedy, that is the best thing about all talk at all parties, perhaps on account of the booze, and the fact that everybody is free again for a little while, and it is permissible and in order to talk about the funny stuff in the world, what somebody said to somebody else at a time when something else was expected of him traditionally har har har har har har. Christ, reader, take my advice, don’t die, Johnny Mercer died, but don’t you, and don’t get the kind of headaches that made Johnny Mercer agree to go to the highest branch of the medical profession for the latest kind of examination and then don’t be told yes, yes sir, yes Johnny Mercer, we’ve found it, you have a brain tumor, it has to come out, because it may be benign but also may not be, and in any case, it appears to be the thing that is hurting your soul by way of pain in your head, so Johnny Mercer agreed and they did their good work, and he died, a great artist, a great man, a great son, a great living member of the human race died, and he is gone, and don’t you do it, and don’t think you may have a brain tumor, too, because thinking about it may start a little one growing in your head, watch out for giving the mystery of cells any hint of fear, because those cells may be like dogs and if they sense you’re afraid of them, they’ll go to work and start multiplying in a kind of disorganized way and hurt you so badly you will risk dying on the operating table, and then lose your bet, and die. Don’t do it.

Not every page of Obituaries manages to squeeze so much into a few lines, but enough do to make it a surprisingly moving experience. Sometimes Saroyan wanders around aimlessly. Sometimes he wanders around and manages to sneak up on himself. And sometimes he manages to sneak up on us, too. I have moments when I have a sudden vision of contracting some devastating disease and shake it off with a shudder, but until I read this passage, I didn’t realize that I was afraid that these thoughts “may be like dogs and if they sense you’re afraid of them, they’ll go to work and start multiplying in a kind of disorganized way and hurt you so badly….”

“Why do I write? Why am I writing this book?” Saroyan asks at one point. His answer is simple: “To keep from dying, of course. That is why we get up in the morning.” And so he kept on getting up and working at his daily writing task, never quite knowing where it would lead but reassured by the thought that at least he was keeping death at bay. As Lawrence Lee and Barry Gifford relate in Saroyan: A Biography, In April 1981, just a few weeks before his death, Saroyan called the San Francisco bureau of the Associated Press to dictate what he wanted to appear in his obituary as his last words: “Everybody has got to die, but I have always believed an exception would be made in my case. Now what?”

Obituaries is available free in e-book formats on the Open Library: Link.

Obituaries, by William Saroyan

Berkeley, California: Creative Arts Book Company

Herbert Gold’s memoir of Saroyan in the San Francisco Chronicle from 2008

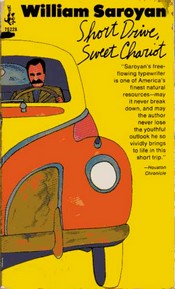

“In the summer of 1963 I bought a 1941 Lincoln limousine in New York, so that I might be chauffeur in California to the few remaining dignitaries in my family,” William Saroyan explains at the start of

“In the summer of 1963 I bought a 1941 Lincoln limousine in New York, so that I might be chauffeur in California to the few remaining dignitaries in my family,” William Saroyan explains at the start of