Excerpt

The clock of world history showed October 14, 1904.

In order to celebrate the historic moment, the Czar had torn himself away from Tsarskoe Selo and from the cradle of his infant son, and had come to Libau to bid his fleet farewell. He was accompanied by a strange-looking, ascetic man, with clever eyes in a hard, cold, merciless face. The words that came from his thin lips were in strange contrast to his forbidding face; they were gentle and pious. He was one of the most powerful men in the empire, the Czar’s trusted adviser and the most hated man in all of Russian: Pobiedonostzeff, Chief Procurate of the Holy Synod. He had arrived to pray for the success of the expedition, and to assist the Czar, as supreme head of the church, in bestowing God’s blessings upon it.

There were flags in every window. People crowded the streets leading to the water front, climbed upon lantern poles, strained against the ropes. Galloping Cossacks cleared a path for exalted visitors, policemen shouted, women fainted, salutes were fired from the ships in the harbor and gaily-colored flags and pennants flew from every masthead.

It was an overcast, gray October day. The brassy strains of military bands cut sharply through the cold autumn air. The men who were lined up on board the ships to receive the Czar’s blessing stood motionless, filled with a numbing, speechless sorrow. The harbor was crowded with steam pinnaces and launches carrying relatives who were trying to get a last glimpse of their loved ones. But the blue-jackets who stood at attention high up on the armor-clad decks of the gray hulls avoided looking down at their wives and fathers and children. They did not wish to open up their hearts which they had sealed against further pain. They knew that they were going to their death. They wanted no tears, they did not wish to go again through the grief of parting. Life and hope were left behind. Thus they set ut — the men whom Russia had defeated.

At last the hour approached for which the whole world had been waiting. In every church throughout Russia prayers were offered up for the success of the expedition. The bells in Libau began to toll; and the emaciated ascetic in the black robes with the gold chain lifted his white claw-like hands to the forbidding sky to invoke the Lord’s blessing and protection upon this armada which was to bring defeat upon the unbelievers.

And beside him stood Czar Nicholas II, a pale, handsome man. His lips moved but no one could understand the words.

And finally a last greeting rumbled over the water as the guns fired their parting salute. Anchor chains rattled, hawsers were loosened and the screws began to turn. The bridges of the ships were lined with officers standing at salute, their eyes staring toward the land, toward the teeming masses of people, the cranes and houses and sheds and churches, and at the white face of the Czar who stood motionless, his hand raised to his cap, watching his fleet sail to make this dream come true. His figure was growing smaller and smaller, and became a tiny speck as the squadron moved out to sea.

Editor’s Comments

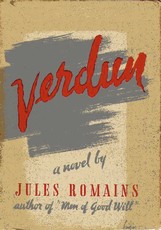

John Lukacs’ comment about The Voyage of Forgotten Men (titled Tsushima in the original German, led me to locate a copy and see how it compared with some of the other “nonfiction novels” he mentioned, including In Cold Blood and Ragtime. I must admit that I at first doubted Lukacs’ identification of the book as a novel. It reads as colorful history recounted by an omniscient narrator and has a bibliography of sources at the end. Nowhere in the U.S. edition is it called a novel, and the reviews of some U.S. critics at the time of its publication suggest that many readers of the English translation believed it was a work of history.

But the German edition clearly states right there in the title: Tsushima: Der Roman eines Seekrieges (The Novel of a Sea Battle). Knowing that this is a novel and not a strict work of history, one can accept more easily those aspects of the book that critics such as Lincoln Colcord complained about. For Thiess is a passionate writer who displays openly his loyalties and dislikes. The Czarist state is “lazy, corrupt, indolent”; the members of the growing revolutionary movements are “microbes,” “a malignant growth in the body of Russia.” His omniscience allows him to describe unrecorded scenes and conversations. He knows the thoughts of the leading figures and can even take a God’s eye view of the battle:

The truly terrifying character of a naval engagement lies in the fact that it is a clash of machine against machine. An airman flying high above the battle area would see only a seemingly calm procession of little ships, following one behind the other in accurately spaced distance, and emitting white puffs of smoke and darker clouds from belching funnels…. But he would not be able to see what is going on deep down in the bellies of the ships.

There the stokers are shoveling mountains of coal into the glowing furnaces, working as fast as they can — and yet they might be working thus on any peaceful day in May…. Fortunately they do not know what is going on above them. They cannot see the number of wounded carried to crowded sick-bays and improvised dressing stations.

Thiess begins his story with the onset of the Russo-Japanese War, the siege of Port Arthur and the entrapment and destruction of much of the Russian First Pacific Squadron. By a combination of general underestimation of Japanese military and naval strength and skills and a circle of advisers of dubious integrity, Czar Nicholas II rejects the obvious option of a negotiated settlement with Japan. Instead, he decides to assemble a Second Pacific Squadron, rushing new ships through the last stages of constructions and hastily patching up long-obsolete old ones, and to sent it on a twenty thousand mile voyage from the Baltic, down around the Cape of Good Hope, across the Indian Ocean, and up past the Philippines and into the Sea of Japan. There, his naval experts tell him, the superior military abilities of the Russian fleet will wipe out the Japanese force and restore Russian control over Korea and Manchuria.

It was a plan gigantic as the country in which it originated, exhilarating in its fantastic, utopian appeal. Whether it could be carried through no one could tell. There were immense obstacles in the way of its achievement. Many naval experts throughout the world considered the whole enterprise an unparalleled piece of lunacy.

In reality, despite its ambitions, Russia was a minor naval power with a force as riddled with inadequacies and corruptions as every other element of the Czarist regime. Few officers, let along sailors, had the experience of a long ocean voyage. The ships were masses of imperfections: armor too thin, drafts too deep, guns and radios too short of range. Their shells had little penetrating power, their torpedoes failed, and their gunners had precious little experience with live firing. Anything but the most rudimentary battle tactics was beyond the limited skills of the crews.

And, Thiess adds, “Then there was the food and supply problem for a fleet of some forty ships which represented a floating city of ten thousand inhabitants. Would it be possible to take along sufficient ammunition, in addition to the other huge stores which were required for a twenty-thousand-mil trip without bases? And lastly, where was the leader for such a gigantic venture?”

With this, in walks the hero of the story, as told by Thiess. From the moment he is given command, Admiral Zinovii Rozhestvensky finds he has to fight two battles. Before he can take on Admiral Togo and his fleet in the Pacific, Rozhestvensky must first overcome the politics and corruption within the Russian government and the limitations of his officers, crews, and ships. Just to muster up an adequate force was challenge enough, but he had also to lead that force on an epic voyage despite the lack of any logistics infrastructure to sustain the fleet.

When Rozhestvensky does manage to assemble and prepare a fleet, two or three key ships are forced to drop back for repairs within the first 24 hours of sailing. Thanks to the many holes in Russia’s patchwork set of alliances, he has to avoid more ports than not. Despite an international incident over an accident off the coast of England, constant breakdowns and repairs, and severe weather, the expedition gets as far as the tiny port of Nosi Be in Madagascar before things fall apart.

There, to the existing supply problems is added an unraveling of the arrangements for coal refueling. As the fleet festers in the tropical port, the situation tips from the difficult into the absurd. The scene resembles something from a novel by Garcia-Marquez:

As the days lengthened into weeks, and the weeks into a month, disease and decay began to attack the ships themselves. These armor-clad giants had been the last reality in the African nightmare, the last tangible link with Russia. And now they themselves became afflicted with tropical sores. Sea moss grew on the hulls, and barnacles, algae and a slimy underwater flora clung like parasites to the bottoms and sides of the ships. On the deck, too, alien creatures had taken possession, increasing with tropical fecundity, and turning the warships into an ill-kept menagerie. The officers had brought animals of every description on board to while away their time, but soon these animals became the real masters of the ships. Screeching monkeys scurried up the masts, swung from the tackle and jumped about in the rigging. Multi-colored parrots perched on the rails, croaking and furiously beating their wings when anyone tried to approach them. Shiny lizards crawled out of the gun barrels and sat on the armored turrets.

After weeks of delay, a series of coaling rendezvouses are set up and the fleet resumes its journey. It evades a Japanese trap as it passes through the narrow straits around Singapore, endures a daily round of expulsions from the French Indochina port of Cam Ranh Bay, and finally takes on its last stores of coal before steaming up the Chinese coast towards the Japanese fleet. Waiting in a line ranged around the island of Tsushima between Korea and Japan, the Japanese — repaired, reinforced, and ready for the fight — have virtually all factors in their favor. Defeat, Rozhestvensky and his crews know, is inevitable.

Yet, as Thiess describes in a riveting account of the battle, the Russians fare better than the Japanese — or they — expect. For a moment early on, before his fleet’s inexperience with battle manouevres leads to a fatal error, it even looks possible that some Rozhestvensky’s squadron might reach Vladivostok. In the end, however, the combination of superior forces and Russian mistakes results in the almost complete destruction of the squadron. Even the torpedo boats are chased down and destroyed or scuttle themselves to avoid capture.

As Thiess relates the story, the remaining command ship surrenders while Rozhestvensky lies aboard, unconscious. Imprisoned in a Japanese hospital, he is finally released after the completion of the Portsmouth peace conference, at which Russia agrees to terms no better than it might have achieved before the Second Pacific Squadron even set out. Rozhestvensky returns to St. Petersburg via the Trans-Siberian railway:

In Tula the train was again stopped by workers and soldiers who had heard that Rozhestvensky was on board and wanted to see him. A voice, a nameless voice, cried out from the throng: “Tell us, Zinovii Petrovich, was there any treason in this?” Rohestvensky called back in a firm voice: “No, there was not treason. We simply were not strong enough, and God did not send us luck.”

Again there was a deathly silence, and once more an unknown voice shouted: “Look at him! Here is one man who has sacrificed himself for our country!” … They were grateful to the one man in high position who had not betrayed them as the rest had done.

While Thiess’ characterization of Rozhestvensky never tips into hagiography, it’s clear that one reason he called this a novel instead of a history is that he deliberately develops the view of Rozhestvensky as the protagonist. Aside from a few arch-villains within the Russian political elite and military, most other figures in the book are enigmas. The men of the squadron are treated as a collective character — the simple, trusting, but lazy serf who proves, in the final test, to have reserves of resolution and sacrifice to outlast most opponents. Written before World War Two, The Voyage of Forgotten Men foreshadows the kind of suffering and resilience seen through four years to fighting on the Eastern Front.

The Voyage of Forgotten Men is perhaps a more subjective account than current tastes appreciate, but there’s no denying the dramatic worth of the story. It’s a gripping tale — even with the ultimate fate of the fleet known from the very beginning of the book, Thiess manages to achieve a remarkable degree of narrative tension — enough to lead one reader reviewing a recent account of the Battle of Tsushima to write, “Without doubt, the best book on this subject is one written by a German between the world wars, Frank Thiess….”

Other Comments

- Lincoln Colcord, Books, 7 November 1937

- The present work, denying once more the human aspects and going far beyond the question of exoneration, attempts at this late date to build Admiral Rozhestvensky up into a hero, a great naval commander, a strategist of superlative ability, the one-eyed public servant in a welter of bureaucratic confusion and national disaster. At times the author grows almost lyrical; faults of character are tossed aside with perfect ease, or turned into virtues by a swift rationalization; facts are cheerfully twisted or evaded. At other times he indulges in sheer fiction, quoting the admiral and others as if he had been present at the scene. The result is a curious hodge-podge of truth and falsehood, and all concerned with a matter so far removed from the present problems and relations of humanity that one can only wonder at it.

- Hanson Baldwin, New York Times, 5 December 1937

- This book has a peculiar topical timeliness in view of the undeclared war in China…. [It] helps to make the present intelligible, and it again pays homage skillfully to events that will never die. But although it describes a great epic, it is itself far from epic quality…. Nevertheless, The Voyage of Forgotten Men is a brave though hopeless tale, well worth the reading.

- Time, 1 November 1937

- Solidly dramatized history of the Russian navy’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, with background emphasis on the Tsarist corruption which led to the fleet’s annihilation at the battle of Tsushima after its epic 20,000-mi. voyage under command of much-maligned Admiral Rozhestvensky, whom Author Thiess attempts to vindicate.

- John Lukacs, Historical Consciousness: The Remembered Past

- … the protean manifestations of this kind of “semi-documentary” or “novelized history” or “documentary novel” or “nonfiction novel” (none of these terms is really satisfactory) is itself the strongest evidence that such a tendency is indeed in the making; and that others may come to create a more perfect model of a genre that may be the genre of the near future, perhaps eventually dominating all forms of narrative literature.

Here is a very random sample of these “new kinds of novels: Tsushima by Frank Thiess …

The Horrors of Love by Jean Dutourd….

What do these books very bad, perhaps only two of them very good (Tsushima and The Horrors of Love) — have in common?

… they represent attempts to construct or even to break through to a new genre — something of which some of their authors are more aware than are others.

Find Out More

Locate a Copy

The Voyage of Forgotten Men, Frank Thiess

Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill, 1937

For my own part, I have to admit that I’ve cracked

For my own part, I have to admit that I’ve cracked  It is true that I haven’t read every one of its 4,256 pages, having sometimes been overcome with yawns in the middle of Jerphanion’s arch and soulful letters to his fellow student Jallez. On the other hand, I have read every word of Vols. I, II, III, IV (in French and English), VIII, and the greater part of Vols. V, VI, and VII. The eight volumes stand before me as I write — 612 cubic inches of reading matter, fully indexed, with more than half again as much to follow. Yet I can’t convince myself that this is a work that belongs somewhere between the “Comedie Humaine” and “Remembrance of Things Past.” I can’t convince myself that it ranks much above ordinary novels in any quality except sheer size.

It is true that I haven’t read every one of its 4,256 pages, having sometimes been overcome with yawns in the middle of Jerphanion’s arch and soulful letters to his fellow student Jallez. On the other hand, I have read every word of Vols. I, II, III, IV (in French and English), VIII, and the greater part of Vols. V, VI, and VII. The eight volumes stand before me as I write — 612 cubic inches of reading matter, fully indexed, with more than half again as much to follow. Yet I can’t convince myself that this is a work that belongs somewhere between the “Comedie Humaine” and “Remembrance of Things Past.” I can’t convince myself that it ranks much above ordinary novels in any quality except sheer size.

Once I returned to Varsity after Christmas I lost no time in starting upon volume one. In this book alone I met about sixty characters, most of whom appeared throughout the series. On and on I went. I paused for the Easter exams; and then while I sought volume four, missing at

Once I returned to Varsity after Christmas I lost no time in starting upon volume one. In this book alone I met about sixty characters, most of whom appeared throughout the series. On and on I went. I paused for the Easter exams; and then while I sought volume four, missing at