Excerpt

I had been sitting all afternoon in the office alone, with my feet on the desk, reading The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Building up a law practice in a depression is a slow way to get rich, but it’s a fine chance to improve the mind, learn card tricks or take up the five-string banjo. Well, here I was with my mind on red hair and high heels, and I went down the elevator in the Santa Fe Building and came out into Commerce Street. I was passing the Waldorf Hotel Bar. This bar was usually full of whores, horse players, and the vendors of razor blades and rubber goods who made the offices in those days. I saw Gail Lindquist at one of the tables just inside the door; she had a tall brew in front of her and was looking out into the street with the enraptured stare seen commonly on the faces of seasoned beer drinkers and Botticelli madonnas. Gail was not the redhead. In fact, I had thought very little of Gail Lindquist up to that time; and if I had just walked off into the Commerce Street traffic and broken a leg or two, or gone upstairs and picked up a dose–anyhow, I looked in and there was Gail.

Gail Lindquist, college graduate, only not of Texas University, but of some place in Southern California, some hick school you never heard of, one of those places where the head of the English department coaches girls’ basketball, heads up dramatics (As You Like It and Charley’s Aunt), and spends his summer vacations on his father-in-law’s farm. A rangy, limed-oak blonde, negligently dressed, sometimes with a delicate white pimple or two on her face (when she had had a fighting letter from her mother as I was later to find out), a small pointed chin, not much jaw to speak of, but with (as I was also to find out) knots of formidable Calvinist muscles along the jaw line, a small wart on one cheek, the loveliest gray eyes you have ever seen, and a fine mind. All this, together with a light, soaring, I’ve-saved-the-last-dance-for-you voice, if you can still say that sort of thing without having people compare you to F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Editor’s Comments

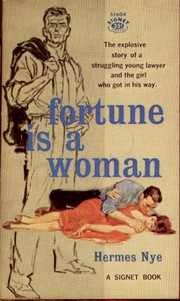

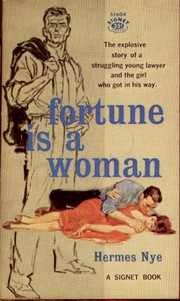

Hermes Nye was born in Chicago, but became a legendary East Texas character: a lawyer, folksinger, folklorist, novelist, humorist, and local liberal activist. Nye clearly never took anything, including himself, too seriously. When, in the midst of the 1960s folk boom, he published a guide to folk songs, he gave it a triply-redundant title that included its own punchline: How to be a folksinger; How to sing and present folksongs; or, The folksinger’s guide; or, Eggs I have laid.

Hermes Nye was born in Chicago, but became a legendary East Texas character: a lawyer, folksinger, folklorist, novelist, humorist, and local liberal activist. Nye clearly never took anything, including himself, too seriously. When, in the midst of the 1960s folk boom, he published a guide to folk songs, he gave it a triply-redundant title that included its own punchline: How to be a folksinger; How to sing and present folksongs; or, The folksinger’s guide; or, Eggs I have laid.

Fortune is a Woman is a genuinely neglected book. First published as a paperback original in 1958, it passed unreviewed out of print and most copies have long since disappeared. The half-dozen or so copies to be found for sale on the Internet run as high as $50 a copy. About its only notice in the last 50 years was its inclusion in James Ward Lee’s 1987 survey, Classics of Texas Fiction.

The novel is narrated by Paul Cotton, a young lawyer getting his start under the wing of a wise and patient veteran of Dallas courts, Harry Alderson, known as “the Chief.” He’s living on an allowance from his father, sharing a room at the YMCA, lusting after a cute waitress at his usual diner, and hoping to hang out his own shingle in a year or two. And he’s depressed: too educated not to have ambitions and too lazy to hold out much hope of realizing them. For him to make a fortune, it will have to land in his lap.

Which is what happens, in a very roundabout and unexpected way–rather as Nye approaches the story himself. Paul and Gail agree to pair up with his roommate on a double date, only to find out the fourth party is the coveted waitress. Paul finds consolation of a sort in Gail’s company and over the next week or so, becomes convinced he’s deeply in love with her.

Gail, unfortunately, is not. She seems to have a complicated relationship or two going in addition to her bemused flirtation with Paul. She also has a taste for exotic forms of rot-gut:

“At the apartment, she had some Mexican liqueur made up out of one part brimstone, eight parts of alcohol and two parts crankcase drippings from Monterrey taxi cabs.” A former lover shows up, as do Gail’s parents, and eventually she’s found, smoking gun in hand, over a man’s body.

In the meantime, Paul has a real case or two, and before he knows it, this boy has more complications going on than his poor little soul can handle. Heart-broken, afraid his short-lived legal career is about to go down in flames, he finds himself leaning out the window of his 11th story office, contemplating a quick way out.

Fortunately for Paul and the reader, Nye is far too amused by life’s comedy to let things get too far out of hand. Most of the loose threads get wound in and haphazardly fastened, leaving Paul with his suddenly-deceased boss’ practice, a win or two under his belt, and enough perspective not to head for the window again.

Frankly, though, the story is the least of this book. What makes this novel a delight to read is Nye’s wry, knowing, and unpretentious voice:

We had a settlement pending in a will case with his firm, Bamberg and Callahan. It was a bastard of a case, the legatees as contentious and stiff-necked as a group of Lutheran schismatics, and money as thick as flies around a boarding-house syrup pitcher. I went up to the sixteenth floor, and into the door with all the names on it; it was a big firm, they had enough lawyers around to make up two football teams including the line coaches and waterboys. The receptionists here had sculptured hair and big breasts and sat at electric typewriters that double-spaced whenever you cleared your throat. Some senior member on his Grand Tour had paid too much money for a lot of seventeenth century Neapolitan oils and these were on every wall, softly lighted; and with the wine-colored carpets and deep leather divans, the place looked like a fifty-dollar whorehouse. Except for the library. The library had everything but the original Magna Carta and the stone tablets of Hammurabi. “Looking up the law at Bam and Call” was a favorite expression among the young lawyers, since it saved you a trip to the courthouse; and there were always those typewriters to look at….

You can tell that Nye must have been a hell of a guy to while away a night in a Dallas bar in. He knows all the town’s streets, offices, taverns, and all its characters–the old money, the new money, the just-getting-by, and the down-and-out. And as the novel takes place in the midst of the Depression, not much separates any of them:

An air swept over me, sour with the smell of home dry-cleaning; the worst air in the world, the air of failure. And not just spiritual or moral failure; but financial failure. There was a secondhand reek to it, blowing off used-car lots and across seas of dependency. You may recognize this failure, amigo, it has its own signature: the eyes of the brave little woman who has to “make do”; the seven o’clock bus; the whiff of rubber cement as you stick the dime shoe-soles onto your Thom McAns, the ping of twelve-year-old Chevrolet doors; the voice that will let you know when there is an opening, or that the truck will be around at three for the bedroom suite.

Another writer gifted with Nye’s narrative voice might have invented a wise-cracking detective like Gregory Macdonald’s Fletch. But I suspect that would have required more design than Nye cared to put into this book. Instead, he manages to pull off two worthy feats. First, he writes a gently comic ballad celebrating his beloved city without glossing over any of her flaws or vices. And second, he manages to take on the Bildungsroman–a form that has been the ruin of many a more ambitious writer–without leaving the reader ready to wring the writer’s or protagonist’s neck–or both–by the book’s end. In its own way, Fortune is a Woman has a lot in common with that now-canonized 20th century masterpiece, The Adventures of Augie March. I have a feeling, though, that if he’d ever found himself sharing a drink with Hermes Nye, Bellow would be the one doing the listening.

Find Out More

Locate a Copy

Fortune is a Woman, by Hermes Nye

New York: Signet Books, December 1958

Hermes Nye was born in Chicago, but became a legendary East Texas character: a lawyer, folksinger, folklorist, novelist, humorist, and local liberal activist. Nye clearly never took anything, including himself, too seriously. When, in the midst of the 1960s folk boom, he published a guide to folk songs, he gave it a triply-redundant title that included its own punchline:

Hermes Nye was born in Chicago, but became a legendary East Texas character: a lawyer, folksinger, folklorist, novelist, humorist, and local liberal activist. Nye clearly never took anything, including himself, too seriously. When, in the midst of the 1960s folk boom, he published a guide to folk songs, he gave it a triply-redundant title that included its own punchline: