Men of Henry Preston Standish’s class did not go around falling off ships in the middle of the ocean; it just was not done, that was all. It was a stupid, childish, unmannerly thing to do, and if there had been anybody’s pardon to beg, Standish would have begged it. People back in New York knew Standish was smooth. His upbringing and education had stressed smoothness. Even as an adolescent Standish had always done the right things. Without being at all snobbish or making a cult of manners Standish was really a gentleman, the good kind, the unobtrusive kind. Falling off a ship caused people a lot of bother. They had to throw out life preservers. The captain and chief engineer had to stop the ship and turn it around. A lifeboat had to be lowered; and then there would the spectacle of Standish, all wet and bedraggled, being returned to the safety of the ship, with all the passengers lining the rail, smiling their encouragement and undoubtedly, later on, offering him innumerable anecdotes about similar mishaps. Falling off a ship was much worse than knocking over a waiter’s tray or stepping on a lady’s train. It was even more embarrassing than the fate of that unfortunate society girl in New York who tripped and fell down a whole flight of stairs while making her grand entrance on the night of her debut. It was humiliating, mortifying. You cursed yourself for being such a fool; you wanted to kick yourself. When you saw other men committing these wretched buffoon’s mistakes you could not find it in your heart to forgive them; you had no pity on their discomfort.

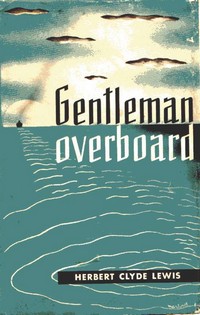

In Gentleman Overboard

In Gentleman Overboard , Herbert Clyde Lewis takes no pity whatsoever on his character’s discomfort. While taking a leisurely cruise from Honolulu to Panama aboard the freighter Arabella, Henry Preston Standish of Central Park West–partner of Pym, Bingley and Standish, member of the Finance, Athletic, and Yale Clubs, father of two–slips on a bit of kitchen grease and tumbles into the Pacific Ocean as he takes an early morning stroll around the ship.

, Herbert Clyde Lewis takes no pity whatsoever on his character’s discomfort. While taking a leisurely cruise from Honolulu to Panama aboard the freighter Arabella, Henry Preston Standish of Central Park West–partner of Pym, Bingley and Standish, member of the Finance, Athletic, and Yale Clubs, father of two–slips on a bit of kitchen grease and tumbles into the Pacific Ocean as he takes an early morning stroll around the ship.

No one notices. Several passengers and crew members think they see him, and what with the rush of the day’s tasks and a general inclination not to bring up unpleasant issues, no one says a thing about his absence until over ten hours later. Grumbling about the loss of time and fuel and the unlikelihood of ever finding a lone man floating in the middle of the ocean, the Captain turns the ship around to search.

Meanwhile, Standish treads water. He takes pride in his mastery of the dead man’s float, something he learned as a boy at the club. After a while, he kicks off his shoes and jacket. A bit later, the shirt and pants go. Finally, he slips off his shorts. This, he realizes, is the first time since childhood he’s been naked in the water.

Overall, Standish does quite well for the first few hours. His spirit is high. He has the self-possession to keep his head in the face of a seemingly hopeless situation. The ship will return for him, after all.

Gradually, though, confidence fades into frustration. It is quite tedious that the ship is taking so long to come back. It does say something about the quality of the Captain and his crew.

He grows hungry and desparately thirsty. “… [N]ever once before in his life had he gone hungry or thisty…. the real meaning of hunger and thirst, to be hungry for bread and thirsty for water, had not existed for him.” He grows tired. Every once in a while he forgets that “he was a doomed man and it was damned annoying when he had to remind himself.”

Night falls. There is still no sign of the ship. Standish grows weaker.

Is he rescued? In a sense, we never really know. Lewis leaves us as Standish’s thoughts grow hazy and dreamy. Perhaps the ship finds him. Perhaps it doesn’t. It’s not really the point. What Lewis does is to take a simple situation–a man falls overboard–and play it out with no fuss or dramatics. So deftly and elegantly that when we begin to feel Standish’s growing fear it comes like a shock, like a plunge into icy waters. What might go through one’s mind? What kinds of emotions would one feel? This is one way it might transpire.

It’s something of an experiment, then. What matters is not whether it succeeds or fails but simply to see what happens. Lewis puts his subject into the experiment and observes. This novel holds his notes. Few scientists could have recorded the results with such an elegant and light touch. It’s been said that a true artist knows when to stop … and does. By this criterion alone, Herbert Clyde Lewis proves himself a true artist with Gentleman Overboard

Locate a Copy

Gentleman Overboard, by Herbert Clyde Lewis

New York: Viking, 1937

and Circus Parade

.

. The book was adapted for the screen as “Harry and Son” in 1984 by Paul Newman, who wrote, directed, and acted in the film. DeCapite’s most recent books are still available from Sparkle Street Press. DeCapite passed away just a few days ago at the age of 84, having lived in Cleveland, in which most of his stories are set, all his life.

movie star of the 1920’s and ’30’s (he’s like Lon Chaney Sr. to the nth degree.) We learn of his fall from fame, and his attempted comeback in the phantasmagorical year of 1968. In his prime he made “Ghoulgantua”, the most terrifying film ever made (about a combination Frankenstein’s monster/vampire.) He created the famous monster “Gila Man” (a sort of werewolf lizard) during the war. Later he was blacklisted for political reasons, went to Germany to make a legendary, unreleased horror movie about the Nazi concentration camps that was supressed by both West and East Germany, and gradually sank into obscurity. Then low-budget Hollywood came calling with an offer to make a cheap Roger Corman-style Edgar Allen Poe rip-off titled “Raven!”

movie star of the 1920’s and ’30’s (he’s like Lon Chaney Sr. to the nth degree.) We learn of his fall from fame, and his attempted comeback in the phantasmagorical year of 1968. In his prime he made “Ghoulgantua”, the most terrifying film ever made (about a combination Frankenstein’s monster/vampire.) He created the famous monster “Gila Man” (a sort of werewolf lizard) during the war. Later he was blacklisted for political reasons, went to Germany to make a legendary, unreleased horror movie about the Nazi concentration camps that was supressed by both West and East Germany, and gradually sank into obscurity. Then low-budget Hollywood came calling with an offer to make a cheap Roger Corman-style Edgar Allen Poe rip-off titled “Raven!” book, Gardner attempts to hold the high ground against contemporaries such as Bellow, Mailer, and the fearsome nouveau romans of

book, Gardner attempts to hold the high ground against contemporaries such as Bellow, Mailer, and the fearsome nouveau romans of  Morley Callaghan is my favorite 20th-century novelist. His

Morley Callaghan is my favorite 20th-century novelist. His  In

In