In the 1951 reference book, American Novelists of Today, it says of Eric Hatch, “He writes entertaining popular novels which are enlivened by a pleasant vein of humor and by light, satirical characterizations.” This is a polite academic way of saying, “Eric Hatch writes screwball comedies.”

Screwball comedies such as “Bringing Up Baby” and “Mr. and Mrs. Smith” were staples of Hollywood film-making in the 1930s and 1940s and a few are now considered among the finest examples of the art. The situations of screwball comedies were usually ridiculous–mistaken identities, cross-dressing, assumed crimes (the same sort of things that worked for Aristophanes and Shakespeare)–but there is one constant: silly idle rich people.

Well, this is exactly the same raw material Eric Hatch mined in nearly 20 novels written between 1928 and the early 1970s–most of them in the first twenty years of that time. It’s no coincidence that the one novel for which Hatch is likely to be remembered today–My Man Godfrey–was made into one of the greatest of all Hollywood screwball comedies. Five Days (later retitled Five Nights

when issued as a Bantam paperback in 1948, mainly to play up the sex angle) is a perfect example.

As the book opens, Beadleston Preece, known in the papers as the “Millionaire Sportsman”, sits dejected on the terrace of his Long Island mansion as night falls. The auctioneers’ men haved just hauled off all his belongings. For reasons he little comprehends, his fortune, so his broker tells him, has evaporated in the stock market and he is now penniless. He begins to think his only recourse is to go up to his bedroom and hang himself when he turns to find a man holding a gun on him.

He turns out to be a burglar all set to rob the house. Preece breaks the bad news to him and soon Swazey (Lionel Stander, if Hollywood had gotten around to filming this) is commiserating alongside. “Say,” Swazey interjects, “did you beat up dis guy what lost your chink for you?” And soon, thanks to Swazey’s immoral leadership, the two are sneaking onto the stock broker’s estate and stealing his fifty-foot yacht.

Over the course of the next five days (or nights, depending on which edition you’re reading), Preece and Swazey manage to accumulate a small band of fellow runaways, including an Episcopalian bishop, a debutante, a girl from the Jersey waterfront, and the unhappy husband of patent-medicine heiress. Their ramblings around Long Island and New York City waters takes them to such fixtures of East Coast society as the Harvard-Yale Regatta and a lavish dinner dance in Newport. And there a few more crimes, such as a break-in at a fancy Newport dress shop, all pulled off with the lightest of excuses and consciences, and lots of hot and cold running booze.

As I read Five Days, I kept picturing the unmade film version. Preece would have to be played by someone with the right touch of naivete–Joel McCrea, probably. Mary from Jersey would have to be young and a bit street-smart–Ginger Roger would be too old, Betty Hutton too young. Bishop Hartley would have to someone with a nice balance of propriety and mischief–Edward Everett Horton, maybe. Lewis Stone, probably not–not mischievous enough.

“Move over, Wodehouse! Make room for Eric Hatch,” wrote a reviewer of one of Eric Hatch’s early novels, and there’s a lot of truth in that statement. P. G. Wodehouse’s reputation is now well-fixed in the literary firmament, despite the utterly frivolous nature of all his work and that bit of unpleasantness during his time in Nazi-occupied France. Yet one can easily argue that much of Hatch’s work shares the same characteristics that have enabled Wodehouse’s work to survive the test of time. The classic Wodehouse novel sits somewhere in the ambiguous zone between the end of the Great War and the start of the Great Depression. Hatch’s period sites about a decade or so later, between the end of Prohibition and the introduction of television. Both build on a solid bedrock of silly, idle, but fundamentally good-natured and tolerant rich people and working class characters with rough exteriors and hearts of gold.

Hatch’s characters aren’t quite as prim as Wodehouse’s. They drink and smoke and break a law or two along the way. And I can’t imagine a Wodehouse woman muttering “Itch-bay” to a shrewish wife, as one of Hatch’s does. But Hatch’s novels have the same sense of being fixed in a particular period while managing to seem timeless, and I have to say I did actually find myself chuckling at a number of points throughout the book. If things in the world were just, which they aren’t, we would see Five Days, Road Show, and Little Darling sitting a few feet down the shelves from The Inimitable Jeeves. But if the rest of the world can’t manage to figure this out, that won’t keep me from giving a few more of Eric Hatch’s novels a try.

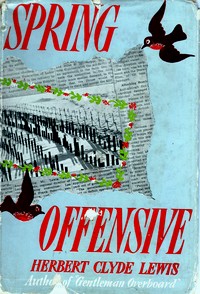

Of course, the Germans didn’t attack the French and British in April 1940, but two months later, in June, and when they did, they wisely bypassed the Maginot Line in favor of a blitzkrieg through the Ardennes and the Lowlands. This is a major reason why

Of course, the Germans didn’t attack the French and British in April 1940, but two months later, in June, and when they did, they wisely bypassed the Maginot Line in favor of a blitzkrieg through the Ardennes and the Lowlands. This is a major reason why