Men of Henry Preston Standish’s class did not go around falling off ships in the middle of the ocean; it just was not done, that was all. It was a stupid, childish, unmannerly thing to do, and if there had been anybody’s pardon to beg, Standish would have begged it. People back in New York knew Standish was smooth. His upbringing and education had stressed smoothness. Even as an adolescent Standish had always done the right things. Without being at all snobbish or making a cult of manners Standish was really a gentleman, the good kind, the unobtrusive kind. Falling off a ship caused people a lot of bother. They had to throw out life preservers. The captain and chief engineer had to stop the ship and turn it around. A lifeboat had to be lowered; and then there would the spectacle of Standish, all wet and bedraggled, being returned to the safety of the ship, with all the passengers lining the rail, smiling their encouragement and undoubtedly, later on, offering him innumerable anecdotes about similar mishaps. Falling off a ship was much worse than knocking over a waiter’s tray or stepping on a lady’s train. It was even more embarrassing than the fate of that unfortunate society girl in New York who tripped and fell down a whole flight of stairs while making her grand entrance on the night of her debut. It was humiliating, mortifying. You cursed yourself for being such a fool; you wanted to kick yourself. When you saw other men committing these wretched buffoon’s mistakes you could not find it in your heart to forgive them; you had no pity on their discomfort.

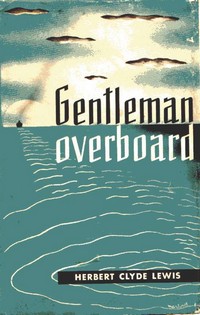

In Gentleman Overboard

In Gentleman Overboard, Herbert Clyde Lewis takes no pity whatsoever on his character’s discomfort. While taking a leisurely cruise from Honolulu to Panama aboard the freighter Arabella, Henry Preston Standish of Central Park West–partner of Pym, Bingley and Standish, member of the Finance, Athletic, and Yale Clubs, father of two–slips on a bit of kitchen grease and tumbles into the Pacific Ocean as he takes an early morning stroll around the ship.

No one notices. Several passengers and crew members think they see him, and what with the rush of the day’s tasks and a general inclination not to bring up unpleasant issues, no one says a thing about his absence until over ten hours later. Grumbling about the loss of time and fuel and the unlikelihood of ever finding a lone man floating in the middle of the ocean, the Captain turns the ship around to search.

Meanwhile, Standish treads water. He takes pride in his mastery of the dead man’s float, something he learned as a boy at the club. After a while, he kicks off his shoes and jacket. A bit later, the shirt and pants go. Finally, he slips off his shorts. This, he realizes, is the first time since childhood he’s been naked in the water.

Overall, Standish does quite well for the first few hours. His spirit is high. He has the self-possession to keep his head in the face of a seemingly hopeless situation. The ship will return for him, after all.

Gradually, though, confidence fades into frustration. It is quite tedious that the ship is taking so long to come back. It does say something about the quality of the Captain and his crew.

He grows hungry and desparately thirsty. “… [N]ever once before in his life had he gone hungry or thisty…. the real meaning of hunger and thirst, to be hungry for bread and thirsty for water, had not existed for him.” He grows tired. Every once in a while he forgets that “he was a doomed man and it was damned annoying when he had to remind himself.”

Night falls. There is still no sign of the ship. Standish grows weaker.

Is he rescued? In a sense, we never really know. Lewis leaves us as Standish’s thoughts grow hazy and dreamy. Perhaps the ship finds him. Perhaps it doesn’t. It’s not really the point. What Lewis does is to take a simple situation–a man falls overboard–and play it out with no fuss or dramatics. So deftly and elegantly that when we begin to feel Standish’s growing fear it comes like a shock, like a plunge into icy waters. What might go through one’s mind? What kinds of emotions would one feel? This is one way it might transpire.

It’s something of an experiment, then. What matters is not whether it succeeds or fails but simply to see what happens. Lewis puts his subject into the experiment and observes. This novel holds his notes. Few scientists could have recorded the results with such an elegant and light touch. It’s been said that a true artist knows when to stop … and does. By this criterion alone, Herbert Clyde Lewis proves himself a true artist with Gentleman Overboard

Locate a Copy

- Find it at Amazon.com: Gentleman Overboard

- Find it at Amazon.co.uk: Gentleman Overboard

- Find it at AddAll.com: Gentleman Overboard

Andrea — Thanks for your comment. I’m greatly indebted to Diego D’Onofrio of La bestia equilateral for arranging to the Spanish translation and publishing Gentleman Overboard as El caballero que cayó al mar back in 2010. Since then, he’s also published Harry Kressing’s sinister little masterpiece, The Cook, as El cocinero. Both of these books are brief, precise, and quietly devastating in their impact–as good as or better than a fair number of much-better known short novels.

Hi! I´m writing from Argentina, where this wonderful novel was rescued by La bestia equilátera, publishing house. I enjoyed reading the book and value all the opinions listed above. It makes one think about the importance (or lack of it) of so many things. And it also made me look further about shipwrecked in literature. Best regards!

Love the book. In addition to themes such as mid-life crisis and illness, mentioned above, I would add that it is very much an example of the proletarian literature of the 1930s. It is not so strange that is has been ignored as an example of this movement, as it does not feature a worker protagonist or show the working class struggles. But read through this lens, it seems clear that it is a post great depression view of the 1900-1920s lifestyle. The view of the “gentleman” who stumbles into a great predicament and adventure reads like classic Jeeves & Wooster in the early parts of the book, but Lewis slowly strips away layers to show how useless this gentleman and all his manners are. Standish is also constantly contrasted with good honest working men such as Nat Adams or the sailor Bjorgström.

Other clear allusions to the class issues of the 1930s are Standish’s role as a stock broker, connecting him to the crash of 1929. Lewis describes him and his Central Park West-lifestyle as having never known hunger or thirst. Seen through the lens of the 1930s literature, this definitely reads as an indictment of the upper class.

Lewis was also active in the leftist cultural group called the Popular Front, and was investigated by the FBI for “communist or otherwise subversive associations” and so I would argue that a reading of Gentleman Overboard as an example of proletariat literature is not far-fetched.

The very theme of falling from the luxury of a cruise ship, into the wildness of nature, is something which in times of economic struggles tend to take on class connotations, as in the case of the movie Overboard. And so Standish’s trials are a sort of “trial by nature” for the upper middle class and for Wall Street in the time of great depression. Just look at how all the other passengers immediately react to the news of Standish being missing, by placing him in class related narratives, such as the suicidal stock broker.

What makes the book great is the same thing which might obscure its political aspects; Lewis does not simply debase Standish as a political comment, but combines the view of the weakness of the gentleman with an honest sympathy for the character, and a real ambition to explore his inner life while showing how the unconscious life-style he has led is destructive.

Thanks for passing this along. That’s a very interesting observation. I hadn’t considered it at all when I read the book, but now that you point it out, I want to slap my forehead and cry out, “Of course!” It makes me want to go back and read it again.

The novel has fallen into the Public Domain – failed to register after 28 years – freely available at Hathi Trust: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b301132 .. use the “Page by Page” view icon for best reading results (can only be viewed on the website, can’t download).

I read it “cover” to cover in under 2 hours, it’s really more of a novella or long short story. Well worthwhile. It seemed to be about confronting ones own mortality and death ie. “mid life crisis”, however it’s equally about confronting disease and terminal illness. When one is diagnosed with, say, cancer, it’s much like being abandoned and alone, all energy into keeping head above water from moment to moment, every trapping of life stripped away and left with the only desire to simply live. Great little book.

I hope I didn’t make the book sound too gloomy, for it’s quite lively and entertaining, despite the grim situation it depicts. Like Marquand’s H. M. Pulham meets “Building a Fire.”

Wow, that sounds like quite a book, like a gentlemanly version of German novelist Jens Rehn’s Nothing in Sight. I may have to try to track it down, though it sounds like I ought to read it on a day when I’m in a very good mood, for it sounds far from cheerful.