|

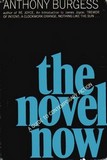

The Novel Now: A Guide to Contemporary Fiction

|

99 Novels: The Best in English Since 1939

|

“Take this little study,” Anthony Burgess writes in his introduction to The Novel Now, “as a beginner’s handbook, no more. It is not, despite the limitations of its author’s taste and knowledge, meant to be a daring or idiosyncratic book: it seeks to instruct, not to inflame.” Focusing primarily on novels written since 1940, Burgess covered many of the English-language (and a few of the foreign) novelists then (and still) considered noteworthy, but in the breadth of his survey, he also highlights a number of books then (and still) underestimated or too-quickly forgotten.

“Take this little study,” Anthony Burgess writes in his introduction to The Novel Now, “as a beginner’s handbook, no more. It is not, despite the limitations of its author’s taste and knowledge, meant to be a daring or idiosyncratic book: it seeks to instruct, not to inflame.” Focusing primarily on novels written since 1940, Burgess covered many of the English-language (and a few of the foreign) novelists then (and still) considered noteworthy, but in the breadth of his survey, he also highlights a number of books then (and still) underestimated or too-quickly forgotten.

Burgess plagiarized The Novel Now liberally in the first half of his 99 Novels: The Best in English Since 1939, published in 1984. “You have here,” he writes in the introduction, “brief accounts of ninety-nine fine novels produced between 1939 and now.”

“In my time I have read a lot of novels in the way of duty; I have read a great number for pleasure as well. I am, I think, qualified to compile a list like the one that awaits you a few pages ahead. The ninety-nine novels I have chosen I have chosen with some, though not with total, confidence. Reading pleasure has not been the sole criterion. I have concentrated mainly on works which have brought something new–in technique or view of the world–to the form.

As with The Novel Now, Burgess principally concerns himself with well-known and critically recognized books but also features a number of novels–some already mentioned in the earlier book–that would not have come to the mind of another reader less widely-read and eclectic.

- The Aerodrome, Rex Warner

- This is a novel which many of us sought during the war (in which books were published, snapped up and then disappeared) but for the most part only read or heard about…. Going home from Gibraltar by troopship in 1945 I found three copies in the ship’s library and at once devoured one of them.

- At Swim-Two-Birds, Flann O’Brien

- It owes a great deal to Joyce, but it is not massive and its touch is light; it even approaches the whimsical. The narrator is an Irish student who, in the intervals of lying in bed and pub-crawling, is writing a novel about a man named Trellis who is writing a book about his enemies who, in revenge, are writing a book about a man named Trellis. In a way, then, the book is a book about writing a book about writing a book.

- The Birthday King, Gabriel Fielding

- … an imaginative penetration into the Germany of 1939-45. It is pre-occupation with ‘the innocent malevolence of the Teutonic mind’, it reads like some exceptionally brilliant translation of a great unkown liberal survivor of the Nazi regime…. it is the sinking of individuality, the turning of himself into an anonymous German, that makes The Birthday King not only his best work but one of the most remarkable novels of the post-war era.

- The Blood of the Lambs, Peter de Vries

- … a joyful masterpiece made out of great personal pain….

- The Body, William Sansom

- … a superb book, perhaps his best. It is a book on a very old theme–that of jealousy. A middle-aged hairdresser comes to believe that his wife, equally mature though still ripely attractive, is having an affair with a hearty, convivial, practical-joking neighbour. His jealousy, like Othello’s, he is driven not into madness but to an obsession with seeing his cuckoldry confirmed. He watches closely and his eyes are sharpened; the details of the external world come through with a clarity which is abnormal but, I think, no hallucinatory. Sansom’s ear, matching his eye, renders the idiom and rhythms of post-war lower-middle class English with a terrible exactness…. By a paradox, Sansom mines into the human spirit by staying on the surface.

- A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight (sequence of 15 novels), Henry Williamson

- The novels that make up this sequence are The Dark Lantern, Donkey Boy, Young Philip Maddison, How Dear Is Life, A Fox Under My Cloak, The Golden Virgin, Love and the Loveless, A Test to the Destruction, The Innocent Moon, It Was the Nightingale, The Power of the Dead, The Phoenix Generation, A Solitary War, Lucifer Before Sunrise and The Gate of the World. Few have read them all. In general, the sequence has failed to engage the critical and public attention it merits. This has something to do, undoubtedly, with Williamson’s political stance, as expressed through his hero Philip Maddison…. Williamson’s style is romantic, though rarely sentimental, and his sensuous response to nature is fresh and surprising. What the sequence lacks is a thematic unity which transcends a mere near-autobiographical record of life in this century.

- Creation, Gore Vidal

- It deals with the fifth century before Christ, the age of the Persian kings Darius and Xerxes and of Buddha, Confucius, Herodotus, Anaxagoras, Socrates and Pericles. Vidal has said that he wanted to read a novel in which Socrates, Buddha, and Confucius all made an appearance: lacking such a book, he had to write it himself…. It is an incredibly detailed and convincing picture of the ancient world. It is thoughtful as well as witty…. Vidal has one of the most interesting minds of all living writers, and he engages here the fundamental problems of humanity without allowing modern knowingness to intrude.

- Darconville’s Cat, Alexander Theroux

- This novel will be termed Joycean by some, specifically those who do not find in Ulysses the urgency of true fiction. It would be more fitting to relate it to such sports as Tristram Shandy and The Anatomy of Melancholy. There is also a strong reek of the dictionary, which may be no bad thing in an age when much fiction has a painfully pared vocabulary. Open arbitrarily and you find on one page: feebs-in overalls; donkeyphuckers; gnoofes; sowskins; ferox-faced oaves; bungpegs; low venereals; pioneeriana…. A word drunk book, but one needs an occasional break from fictional sobriety.

- The Disenchanted, Budd Schulberg

- The book is about Hollywood in the thirties, but it is also about a great decayed novelist, Manley Halliday, who is a thinly disguised Scott Fitzgerald…. This is a haunting novel. No fiction has ever done better at presenting the inner torments of a writer in decline, nor at suggesting the fundamental nobility of artistic dedication.

- The Doctor’s Wife, Brian Moore

- Sheila Redden, Irish Catholic, thirty-eight, a mother, married to a Catholic doctor in Belfast, falls in love with an American twelve years her junior on holiday in Villefranche. The situation is not uncommon in fiction. What is original in this novel is the manner in which the moral dimension of the situation is treated…. Sheila’s agonies are real, and the paradox of her seeming to be, for the first time in her life, in a state of grace when she is technically sinnin has a poignancy which the cool, simple, objective prose does not seek to poeticise. Moore has never written a bad novel, but the moral profundity of this one gives it a rare distinction.

- An Error in Judgment, Pamela Hansford Johnson

- No novel of any complexity can ever have the directness of a moral tract, but the virtue of Pamela Hansford Johnson’s work often lies in its power to present the great issues nakedly–forcing us not so much to a decision as to a realization of the hopelessness of decisions.

- Facial Justice, L.P. Hartley

- … a novel which lives in an area where the dystopian vision and the pure moral fable overlap…. his most imaginative work…. An attempt to build a moral world has resulted in an outlawing of envy and the competitive urge. There must be no great beauty, neither in body (which sackcloth covers, anyway) nor in face. A girl who feels herself ‘facially underprivileged’ can be fitted with a standard Beta face, neither ugly nor beautiful…. One sees a great deal of our own age in Hartley’s fantastic future….

- Farewell Companions, James Plunkett

- This is an ambitious panorama of Dublin life in a time of change and the resistance of change. It is difficult to write a long Dublin novel since Ulysses, but Plunkett has produced an unjoycean work of great architectonic skill which encapsulates vividly the era when Ireland opted out of the world. This is quite an achievement.

- Fowler’s End, Gerald Kersh

- … one of the funniest of post-war novels, and strangely neglected….

- The Fox in the Attic, Richard Hughes

- … a masterpiece in its own right…. Mastery of narrative, management of situation, rendering of time and place are exceptionally powerful: the atmosphere of the Welsh town is wonderfully caught, and the corrupt adult world is marvellously symbolized in, for instance, the foyer of the big German hotel, with its subtle odours of dyspepsia. Hughes died with his scheme unrealized, but we must be grateful for what we have.

- Heartland, Wilson Harris

- In Heartland, with immense economy, he shows the confrontation between logic and magic. Stevenson comes with his machinery to exploit the natural resources of up-river Guiana and is profoundly disturbed by an ancient world he cannot understand and so fears…. Harris has the courage to realize the impossibility of conveying, with the ordinary devices of the prose-novel, states of mind corresponding to the horror and grandeur of primeval nature…. He is probably the best of the Caribbean novelists.

- The Image Men, J.B. Priestley

- Acknowledged as a competent popular playwright and a decidedly lowbrow novelist, Priestley has been unfairly treated by the “intellectual” critics. Lively, humane, picaresque, he has been sneered at as “the gasfire Dickens.” It seems to me dangerous to ignore a novel like The Image Men, a two-volume extravaganze longer than Bleak House and not less crammed with characters. Priestley, like Dickens, has a social message: we are living more and more in a world of facile images and less and less in our blood, guts, and intelligence…. It lacks ambiguity, fine writing, the poetic touch, but it is honest, vital, even thoughtful. It is also, which too many admired novels are not, vastly entertaining.

- Late Call, Angus Wilson

- This may be considered, among other things, to be a study of the New Town…. This, whether we like it or not, is reality. It is the concern with the terrifying and exalting essences underlying the TV Times, the drama club committee meeting and the kitchen crammed with gadgets that gives this novel power. Wilson makes no judgments, but, frightening as life can be, he is on the side of life. His eye catches the surface of the contemporary world with marvellous accuracy, but he is not afraid to descend into the dark mines of the human spirit.

- Life in the West, Brian Aldiss

- … Life in the West is a finely crafted work with a wide social range and a large intellectual content. It conerns Thomas C. Squire, a successful specialist in media theory and practice, now in handsome early middle age and facing the collapse of his marriage, the abandonment of his Georgian mansion, the approaching dissolution of a great family name. We could call the book a novel of mid-life crisis, but it seems better to see Squire’s situation as emblematic of that of the West in an age of recession…. This is a rich book, though not afraid of thought, full of vital dialectic and rounded characters.

- Living, Henry Green

- Living comes out of Green’s own experience as a worker in the Midlands factory which belongs to the Green family, and it is perhaps the most piquant, exact, and heartening novel of industrial life we possess. After all, it is unusual to find an Eton and Oxford man with a large literary talent entering a milieu most often serving, so far as literature is concerned, anti-capitalist growls; this novel has to be unique. The point about Living is that it is about living: the workers are not statistics in an industrial report but people with their own concerns and aspirations. They are like the pigeons which they keep in their lofts–homebound and yet free-and which flutter and whirr throughout the novel as a unifying symbol.

- The Lockwood Concern, John O’Hara

- …The Lockwood Concern, which O’Hara called “an old-fashioned morality novel,” transcends both the author’s declared intetion and the somewhat melodramatic plot…. The book looks, on the surface, like a highly contrived melodrama, but there is a good deal of complexity in it. If George Lockwood is a monster, he is the kind of monster who exhibits the vitality without which America could hardly survive. The rise of the rich is emblematic of the forming of human values which, in America, depend on impulse and energy. O’Hara’s women characters are always credible: more than any writer of his time he knew the ruthlessness and the sexual appetites hidden under the show of softness.

- No Highway, Nevil Shute

- … No Highway must be looked on with awe as a rare novel that has changed not social thinking but aerodynamic doctrine. The courage of a dim disregarded theoretical engineer in sticking to convictions that are derided, his domestic life with his motherless daughter (who has the gift of extrasensory perception) and his bizarre relationship with a famous film star (one of the passengers on the fatigued plan he ruthlessly grounds) are presented with sharp humor and compassion. It is also good to have a novel so firmly based on the facts of the world of technology.

- Pavane, Keith Roberts

- This was probably the first full-length exercise in the fiction of hypothesis, or alternative history, and, with Kingsley Amis’s The Alteration (which I have no room to include), still the best. We have to imagine that Queen Elizabeth I was assassinated in 1588, that there was a massacre of English Catholics and Spanish invasion of a land torn and divided… The virtue of the book lies less in its ideas than in its invention of a modern England that is also medieval: it is a striking work of the imagination.

- Sabaria, Gusztav Rab

- He still awats recognition in the West and deserves it on the strength of one novel alone–Sabaria. This develops very skillfully a theme … the conflict of Christianity and Communism…. The conflict between Church and State is not delineated in the usual black-and-white of a puppet play. The tragedy of life lies in the fact that good and evil reside where they will, not where a uniform of an office leads us to expect; that a Church can contain selfish and corruptible priests and a Communist Party can show humanity…. This is a very interesting and disturbing book.

- Strangers and Brothers [sequence of 11 novels], C.P. Snow

- [The novels are: Time of Hope (1949);

Strangers and Brothers (1940);

The Conscience of the Rich (1958);

The Light and the Dark (1947);

The Masters (1951);

The New Men (1954);

Homecomings (1956);

The Affair (1960);

The Corridors of Power (1964);

The Sleep of Reason (1968); and

Last Things (1970).]

This sequence is a very considerable achievement, despite the flatness of the writing and the almost willful evasion of the mythic and poetic. It brings into the novel themes and locales never seen before (except perhaps in Trollope). Neglected since Snow’s death, it deserves to be reconsidered as a highly serious attempt to depict the British class system and the distribution of power. The work has authority: it is not the dream of a slippered recluse but of a man actively involved in the practical mechanics of high policy-making. - Sweet Dreams, Michael Frayn

- This is a fantasy presented with disarming lightness of touch and tone which is profounder than it looks…. But Frayn, who refrains from comment, who is altogether too charming–like his characters–with his easy-going colloquial prose, is fundamentally grim and sardonic. Cambridge cannot redesign the universe. The dream ends. Still, it might be a very pleasant if these awfully nice and intelligent Cantabrians of good family could replace blind chance or grumbling bloody bearded Jehovah. There is no sin here, only liberal errors. Frayn was trained as a philosopher. This is a philosophical novel. It is deceptively tough.

- Too Long in the West, Balachandra Rajan

- … witty, profound, and beautifully written…. a satirical study of modern Indian life as seen from the angle of Nalini, a girl who has returned to her remote muddy village from three years at Columbia University. She has, in fact, been too long in the West to take kindly to the throng of suitors who, in reply to her father’s newspaper advertisement, have come to compete for her hand. Rajan uses the Indian attitude to marriage as a focus for some good-humoured but telling attacks on a too-conservative way of life that must learn to come to terms with the West.

- The Vendor of Sweets, R.K. Narayan

- Narayan is the best of the Indian writers in English–graceful, economical, realistic but drawn to fantasy, gently humorous–and the fictional territory of Malgudi he has created is perhaps as important a contribution to modern literature as Patrick White’s Sarsaparilla or even Hardy’s Wessex. He writes so consistently well that it is painful to limit him to a single book, but The Vendor of Sweets can be taken as a way into the others.

3 thoughts on “Anthony Burgess”