Forgotten Treasures: A Symposium

The Los Angeles Times, 26 December 1999

Editor’s note from the original article:

“With the turn of the millennial odometer now hard upon us, we asked a number of writers to share with us their neglected classics of the century, books they love but which, for one reason or another, have yet to find the readers they so richly deserve.”

- Anthony Bailey

- From August 1914 to January 1915, a 28-year-old French historian of middle-class upbringing and Jewish ancestry named Marc Bloch was an infantry sergeant in the hastily dug trenches of the muddy Marne valley, 30 yards from the Germans. He kept a journal. In the spring and early summer of 1940, Bloch–by then 54 and the author of several celebrated works of medieval history–was once again in uniform. He was a captain, the oldest (so he claimed) in the French forces, and in charge of fuel supplies at the northern end of the French line. When the Germans broke though in May, he witnessed the disintegration of the French positions at close hand. He was evacuated from Dunkirk on a British paddle-steamer, spent two days in England and returned across the Channel to Normandy to rejoin the French army. When Petain capitulated, Bloch put on civilian clothes and went to Lyons, his birthplace. There he wrote, taught and became one of the leaders of the Resistance. In 1944 he was captured by the Gestapo, tortured and, 10 days after D-Day, executed; his last words to the firing squad, “Vive La France!”

Bloch’s short journal of World War I, Souvenirs de Guerre 1914- 15, was published in Paris in 1969 and in English by Cornell University Press in 1980. Bloch’s account of the French collapse in 1940 was written in the late summer of that appalling year, “when the fate of the French no longer depended on the French.” L’etrange defaite was brought out in Paris in 1946 and as Strange Defeat by Oxford University Press in 1949. The two books are complementary: the first full of battlefield chaos, discomfort and courage, seen at ground level; the second, also full of chaos, seen somewhat more professorially, from a higher level at headquarters, albeit often under fire, and with a historian’s eye for a larger picture. Bloch realized in 1940 that the flabby and sluggish French general staff was still fighting World War I, but the Germans were not. They rarely did what the French expected them to do. They understood speed. They had grasped a 20th century “idea of distance” and didn’t mean to get bogged down again in static confrontation. Their blitzkreig worked, the Maginot Line was turned and the Third Republic was finished.

Bloch’s short journal of World War I, Souvenirs de Guerre 1914- 15, was published in Paris in 1969 and in English by Cornell University Press in 1980. Bloch’s account of the French collapse in 1940 was written in the late summer of that appalling year, “when the fate of the French no longer depended on the French.” L’etrange defaite was brought out in Paris in 1946 and as Strange Defeat by Oxford University Press in 1949. The two books are complementary: the first full of battlefield chaos, discomfort and courage, seen at ground level; the second, also full of chaos, seen somewhat more professorially, from a higher level at headquarters, albeit often under fire, and with a historian’s eye for a larger picture. Bloch realized in 1940 that the flabby and sluggish French general staff was still fighting World War I, but the Germans were not. They rarely did what the French expected them to do. They understood speed. They had grasped a 20th century “idea of distance” and didn’t mean to get bogged down again in static confrontation. Their blitzkreig worked, the Maginot Line was turned and the Third Republic was finished.Bloch is well known as a great historian of the Middle Ages, but I recommend these two personal “testimonies” of his that remind us that he was also a born fighter, a patriot and a robust thinker in his own time–a great man who, when things were at their worst in 1940, when the fate of France was no longer in its own hands, wrote that he found it impossible to despair for the French people.

- Gary Indiana

- It would be easy enough, and relatively accurate, to say that literature itself is the “most neglected” art form in our overwhelmingly visual culture, though almost everything we see starts from writing of some kind and the visual media are word-dependent in ways that are more or less invisible to the cultural consumer. To talk only of the literary canon and what the elite that cares about it tends to ignore or give short weight to, at least 30 books readily come to mind.

The two I think of first are Stefan Zweig’s Beware of Pity and Witold Gombrowicz’s Ferdydurke. They could hardly be more dissimilar in sensibility, yet both are about the radical changes in consciousness wrought by World War I and the attendant collapse of the Old World Order. Zweig’s novel mainly describes the world that disappeared during this century’s first apocalypse. Gombrowicz’s addresses the queasy and doomed “modernity” that followed it. Both are important to me as narratives that demonstrate that all great stories have a posthumous quality and that as a writer, one is always a dead person whispering into the ear of the present.

- John Lukacs

-

It is a truth not–well, not yet–universally acknowledged that the novel, as such, is in terminal decline. It had a fabulous run for about 150 years but for the last 50 years–no, longer. Other hybrids appear in its wakes: but the “classic” novel, written in the third- person singular, is passe.

But there are exceptions. And a stunning exception is the French Jean Dutourd’s Les horreurs d’amour (1962, I think; American edition: The Horrors of Love (1965?). One oddity about it is that it is written in the second-person singular; it is a long dialogue between two super-intelligent Frenchmen (both sides of Dutourd’s own character) walking through Paris, ambling in and out restaurants, reconstructing the pride and fall of a Parisian politician who gradually falls in love with his younger mistress and ends up in jail. It is a delicious and profound work of art, from beginning to end. Andre Maurois likened it to Proust; but in some ways it is better than Proust, sprightlier and more imaginative. The language itself is superb. Dutourd, now in his 70s, writes many books; of course some are better than others; he is also a columnist and dabbles in politics, sometimes unnecessarily, but no matter. But The Horrors of Love and another, entirely different Dutourd masterpiece, Bon Beurre (1952?) (Best Butter, also available in English), a satire, have a stunning recognition in common. This is that, yes, ideas count more than does matter; but (contrary to Hegel or Dostoevski or Nietzsche, whom Dutourd of course does not deign to mention) what men do to ideas is infinitely more important–and complex–than what ideas do to men. The villain of Bon Beurre— and, in a way, the protagonist of The Horrors of Love–are opportunists: but opportunities well beyond (and beneath) the Machiavellian prototype. They change their ideas constantly, which comes to them naturally. (In this way Dutourd, especially in Best Butter, is a more subtle satirist than Waugh: his villains wear and discard and change their ideas from time to time whereas Waugh’s villains are incarnations of the very same, usually stupid, ideas).

And now in what–not very accurately–is still called nonfiction (that boundary between what is fiction and nonfiction is corroding fast, like the Iron Curtain decades before its ultimate demise) something at least similar is the principal, and great contribution of the English thinker Owen Barfield (d. 1998) about whom C.S. Lewis, his friend, once said that “Owen is the greater thinker of us two.” T.S. Eliot about Barfield: His thought “is very far from the ordinary routes of intellectual shipping.” It may be summed up simply: Mind Precedes Matter. Reading Barfield all those massive mountains of materialism crumble to a smoking hulk. He hardly wrote anything before he was 50; his books are available without much difficulty. History in English Words; Speaker’s Meaning and Saving the Appearances are the first three to read.

- Andre Aciman

- Count d’Orgel’s Ball came out scarcely a few months after its author, Raymond Radiguet, died at the age of 20 in 1923. Edited by Jean Cocteau, his lover, Radiguet’s second novel was an instant success.

His first novel, published when he was only 16, draws from his own teenage love affair with a married woman whose husband was away fighting the Germans in the trenches. That too had been an instant success. Count d’Orgel’s Ball, far tamer, is the story of the platonic love of a young man for a young married woman, who, like the Princess de Cleves of the eponymous 17th century novel, is equally in love with him. Their love is chaste, and everyone’s bashful, and scruples spin about each like light from a ballroom sphere; but in the minefield of the human heart, it is shame, not lovesickness, that knows exactly where to hurt.

His first novel, published when he was only 16, draws from his own teenage love affair with a married woman whose husband was away fighting the Germans in the trenches. That too had been an instant success. Count d’Orgel’s Ball, far tamer, is the story of the platonic love of a young man for a young married woman, who, like the Princess de Cleves of the eponymous 17th century novel, is equally in love with him. Their love is chaste, and everyone’s bashful, and scruples spin about each like light from a ballroom sphere; but in the minefield of the human heart, it is shame, not lovesickness, that knows exactly where to hurt.

Neither he nor she ever speaks of their love to each other but, one night, at the end of the novel, the wife does tell her husband of her guilty crush for the young bachelor. The urbane, world-wise husband would like nothing better than to dismiss the whole affair and blame her overstrained nerves. He orders her to go to sleep and promises to discuss the matter with her in the morning. But the reader knows–and the spouses know it too–they won’t.

With the exception of Proust, no author in the 20th century had cut into the insidious mechanisms of the human heart with so unsparing or so wicked a scalpel as Radiguet. His clipped sentences unsaddle all of our soulful high-minded stirrings. No one is acquitted; and everyone, as in every good French tale from Les Liaisons dangereuses to “Claire’s Knee,” turns out to be an accomplished liar. Some may be reluctant to lie to others, but no one thinks twice about lying to himself. As we all know but never wish to admit, the true seat of love is not desire; it is repression.

- Wendy Lesser

- If Arnold Bennett is the most unfairly neglected of 20th century writers, then Riceyman Steps is probably his most unduly neglected work. Published in 1923, it describes–no, conveys–in fascinating and pathetic and at the same time humorous detail the life of a London miser, his overly loyal wife and their valiantly practical servant. Perhaps because the miser is a used-book seller, this novel is a favorite with the secondhand book dealers, which is a lucky thing, since they are virtually the only source for it: Riceyman Steps has been out of print for most of the last 75 years.

- Robert Conquest

- It’s hard to think of a really fine book that is totally neglected. Still, I seldom come across anyone who has read Norman Cohn’s The Pursuit of the Millennium doubtless because its theme is chiliastic sects of 500 years ago. But (especially in its expanded later edition), it is uniquely wise and informative about the nature, recruitment and delusions of such movements–then and now.

- Carlos Fuentes

-

Paradiso, a grand baroque evocation of Havana by the Cuban poet Jose

Lezama Lima, is one of the half-dozen greatest novels in the Spanish language this century. Grande Sertao, Veredas [published in English as The Devil to Pay in the Backlands by the Brazilian Joao Guimaraes Rosa is the greatest novel of his country–and one of the most extraordinary attempts to render simultaneity of time and space in the modern novel. In the United States, I believe that the work of Glenway Wescott has been notoriously overlooked. Also, I find it hard to obtain contemporary editions of a great journalist, Vincent Sheean, and of the superb work of historical criticism, Van Wyck Brooks’ The Flowering of New England. - Pico Iyer

-

Every traveler journeys to a place not shown on a map and reports back from a location known only to himself. That is one reason, and one, why the most deply involving travel-book I can remember reading, and one of the most hypnotic detective stories, too, throwing off its excitement like an incandescent flare, is, in fact, a work of literary criticism: The Road to Xanadu by John Livingston Lowes. Brought back to life by Picador Books in London in the mid-’70s but too often forgotten, it is the tale of a professor of Chaucer burrowing for a reference to Purchas in the British Museum, soon after World War I, who suddenly stumbles upon a notebook of Coleridge’s printed only in an obscure periodical about German philology. In it he finds a phrase that reminds him of “Kubla Khan,” a fragment that evokes the Ancient Mariner, and before he knows it, with an explorer’s sense of serendipity, he is being led through the subterranean passageways, down into the corners and past the half- formed stalagmites of the poet’s haunted imagination, seeing how this phrase of Bartram’s and that book of Erasmus’ somehow coalesced in the sleeping man’s mind to make something utterly his own.

The poems themselves, steeped in opium and talismanic in their cadences, have long cast a spell over every kind of reader–Bruce Chatwin, in Patagonia, claimed to find another source for the Mariner in an old Elizabethan journey. And Coleridge, of course, was the British poet most responsible for bringing over formal theories of the Imagination and the Fancy from German Romanticism. But just as the bard tended to live out his ideas more compellingly than he formulated them, so a professor a hundred years later got waylaid from his ostensible theme and tumbled down a trap door into the subconscious. The Road to Xanadu begins to outline the contours of the mind–to show how the imagination works (in both subject and author)–more vividly than anything in Freud; but what makes it ultimately enduring is that it performs an act we usually associate with religious texts: It casts a light upon mystery while respecting the fact that the essence of the sublime will always remain far beyond our reckoning.

- Nadine Gordimer

-

More than forty years ago a boy of nineteen working in a country store in Zululand began to write a novel. He finished it when he ‘was 21 and sent it to Leonard and Virginia Woolf, who published it in 1926. Turbott Wolfe was the work of an angry young man, but it was no tantrum; events have shown his voice to be prophetic, echoing louder and louder from legislation to bloodshed, down the years. The boy of 19 understood what the world, from Alabama to Johannesburg, has come to realize only recently: that the impact of Western materialism on Africa was not a one-way process. In the words of one of his characters–‘Native question indeed. . . .’ It isn’t a question. It’s an answer.”

I wrote the above in 1965, and during the years since then, while the century has approached its end, the prophesy has been fulfilled– not only for Africa, but for the “native” populations of many countries. The 19-year-old was William Plomer, an Englishman born in South Africa, who lived there as a child, went back as a young man, lived and wrote in Japan, became a wonderful poet at home in England. The novel is recounted Conrad-style, as a narrative told to Plomer by Turbott Wolfe dying in old age. Its obvious autobiographical elements become revelatory, in passion, satire, as Wolfe experiences the colonial world in microcosm: from behind the counter of a general store. Everything is vividly there, larger than the compass of the scene, marvelously recognizable but not one-dimensional: the sanctimonious priest, the well-meaning missionary, the home-grown coarseness of the settler convinced of his God-given superiority to the local population, even the beginnings of a liberation movement in the person of a young woman afire with her discovery of communism. And there is Wolfe’s iconoclastic assault on the Western conception of beauty in his vision of it as exemplified in a black peasant girl. The novel is a unique attack on vulgarity, personal, social, political–everywhere you care to place its lens. Plomer, aged, remained Plomer under a gentle and courtly exterior. Asked why he hadn’t written more than a handful of books, he once answered: “Literature has its battery hens; I was a wilder fowl.” And that’s what he is to me.

- Simon Leys

-

I wish I could have replied to the interesting question put by the Los Angeles Times Book Review, but it seemed to present (at least for me) an insoluble contradiction: considering the books which I treasure most, I realize that all of them are already well-known. This, after all, is quite natural; for, when a piece of writing has genuine value or beauty, it is unlikely that it will remain ignored for long or that it may ever fall into oblivion.

Still, here is my little selection–even though it does not abide by the rules of the game (since these books are justly famous already; yet, for various reasons, they are perhaps not reaching now the wider readership they obviously deserve). In chronological order:

* G.K. Chesterton: The Man Who Was Thursday (1908): The only novel in the entire history of fiction which ever managed to introduce God as a plausible character!

* Natsume Soseki: Kokoro (1914) (in E. McClellan’s translation): I know of no other novel written in our century that possesses such mysterious simplicity–such subtle and heartrending purity.

* F.A. Worsley: Shackleton’s Boat Journey (1931?): An extraordinary narrative of survival. There are desperate physical trials which can be overcome only by the will of man–no animal would survive them!

* C.S. Lewis: The Abolition of Man (1943): A less-known essay by an otherwise famous author, yet perhaps his most important work. In a sense, it also deals with survival (a theme worth pondering as we enter the new millennium): Can modern man survive the moral collapse of his culture?

- Eugen Weber

- If you will not read Proust about the Dreyfus Affair because Proust is about so many other things (including finger food), your next best bet would be Roger Martin du Gard’s Jean Barois, which etches the ideological atmosphere in which the Affair played itself out and also the broader context of civil and religious war not just in the streets but within families too. Theatrical in construction, intellectual in substance, the novel, published in 1913, deals with conflicts of science and religion, reason and faith, in fin de siecle terms that retain their freshness and make du Gard, as Camus once called him, our perpetual contemporary. The author received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1937, but Jean Barois in English has long been out of print–perhaps because it features less sex and more thought than our age can stomach.

- Jacques Barzun

- The writings of John Jay Chapman deserve a place in public esteem and have not received it, even though Edmund Wilson proclaimed that he is a figure of importance. From Practical Agitation in 1900, which deals astutely with American politics, to the volumes of collected essays about American culture and world literature, Chapman contributed a vision of life and letters not found elsewhere. That in 1912 he went to the scene of a lynching in Pennsylvania to hold, alone on the spot and at the risk of his life, what he called a prayer meeting in atonement should have drawn attention to the existence of an uncommon mind. As a critic, his studies, ranging from the Greeks to Shakespeare, Shaw and William James, show what learning free of professionalism, either academic or journalistic, can do to make literature something other than propaganda or a pastime.

- Julius Lester

-

Two books come to mind: Mojo Hand by Jane Phillips is a novel about a light-skinned young black woman who goes in search of an old blues singer whom she knows only through his old records. The only novel I know of by a very talented young black woman writer who preceded the black literary renaissance.

And Joseph and His Brothers by Thomas Mann, one of the most stunning literary achievements of this or any century. With his extraordinary command of language and his vision of the place of myth in human lives, Mann’s tetralogy still amazes.

- Thomas Flanagan

-

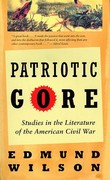

The Civil War lives within the American imagination as a chief shaper of our cultural and social identities. The North, victors in what had become total war waged against an entire society, emerged as a giant of the new industrial world culture. The South survived as the one part of the country to have experienced conquest and defeat. To that war, and to the cultures it would transform, there is no surer guide than Edmund Wilson’s Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the Civil War.Wilson uses the word “literature” to embrace a wide range of expression–the responses to the war of our major artists, Melville, Whitman, Hawthorne, Twain; a host of genuine if lesser artists like Lanier and Cable; diarists and songwriters; the memoirs of Union and Confederate generals and politicians, of slave-owners and abolitionists, novelists and writers of patriotic romances; the recollections of citizens whose loyalties and subversions are less easily named. Only one segment is underrepresented–the African- Americans whose enslaved condition was, after all, what the war was all about. Perhaps. Historians are still arguing the point.

In one sense, Wilson was ahead of his time: like some current historicists, he excludes nothing which provides him, and us, imaginative insight into the conflict. But unlike them, he knows and honors high literature and distinguishes it from low. To get to the low, he hauls from the dustbin such popular romancers as Thomas Nelson Page; to honor the high, he writes with eloquence about Abraham Lincoln’s prose and the perplexed and perplexing figures of Melville and Bierce.

Edmund Wilson was himself a figure of consequence in the history of American culture–a belated Atlantic seaboard aristocrat, well- read beyond the farthest shores of erudition, cantankerous, companionable, rock-solid in a shaking world. His college friend, F. Scott Fitzgerald, called him his “literary conscience.” We all should.

- Dave Hickey

- My vote goes to Christina Stead’s The Man Who Loved Children. It’s a great icy novel, a combat-dream inducing experience for the reader and a truly horrendous disquisition on what goes wrong with families. The reasons for its neglect are simple enough. It was written by a tough-minded lefty Aussie lassie and published on the verge of World War II. This constitutes bad luck in spades, but The Man Who Loved Children remains a spectacular and spectacularly adult book. One for the century.

- Robert Giroux

- The Enormous Room by E.E. Cummings, a neglected American masterpiece, written in the author’s early 20s, his first book and a true story, was published by Boni & Liveright in 1922. John V.A. Weaver praised the book as “a literary achievement of the highest order . . . the most interesting book the war (WWI) has produced.” Cummings, who had earned his Harvard M.A. in 1916, volunteered a year later for the Red Cross ambulance corps in France with his friend, “W.S.B.” Censors intercepted B.’s wild letters, critical of stupid French bureaucracy, whereupon he and Cummings–guilty by association- -were carted off, without being charged or tried, to the camp at Orne called Forte de la Triage de la Ferte. All kinds of suspects were herded into one enormous “oblong room, about 80 by 40” feet, with a vaulted ceiling. Cummings, an innovative writer who became a celebrated poet, kept his sanity by observing how the hundreds of inmates, ranging from one artist who knew Cezanne to the lowest dregs of humanity, were viciously treated by guards. They come alive in the book as individual characters–Jean le Negre, Apollyn, Mexique, One- Eyed Dahveed, Garibaldi, Judas, Rockyfeller, Young Pole, the Zulu and so on–from the admirable to the swinish. The author and W.S.B. escape after brutal months only because Cumming’s father, the Rev. Edward Cummings, a Unitarian minister, could not learn from French authorities where his son was located, after which the U.S. embassy in Paris cabled that his son had left France on a ship that had sunk and a week later that they were mistaken, until his memorable letters to President Wilson, quoted in the preface, effected their release. T.E. Lawrence of Arabia brought about the book’s publication in London (Cape) in 1928, with a preface by Robert Graves extolling its “truthfulness” and calling it “modern in feeling” and “new-world in pedigree.” Both editions are out of print. I was Cummings’ editor in the 1950s and edited his Poems: 1923-1954 and couldn’t acquire the rights to The Enormous Room. This 20th century classic deserves to be republished.

- John Banville

- I first read James Gould Cozzens’ By Love Possessed when I was a teenager and therefore too young to know that I was making a bad fashion blunder. By that time, which was the beginning of the 1960s, Cozzens’s reputation had been thoroughly rubbed out by one of the hit- men at Partisan Review–Dwight McDonald, perhaps, or Philip Rahv, one of the mighty who are themselves by now half forgotten–and it was safe to read only Mailer or Roth or Bellow. But I thought then, and I still think, that Cozzens’ tragic portrait of small-town WASP America was accurate, elegant and in its way as tough as, or tougher than, any of the work of the New York-Chicago school. The spectacle of the ironically named Arthur Winner, a decent man in a mean time, being tarnished by life’s petty falsehoods is deeply affecting, yet bracing too, in the subtle but relentless way it is described. Cozzens was no genius, but this novel (and yes, the title does not help) deserves to live.

- Benjamin Schwarz

-

Far too many Americans who admire Evelyn Waugh’s novels know only the farcical, satiric ones–Scoop, Black Mischief, The Loved One and, inevitably, Brideshead Revisited. They’ve never heard of his masterpiece, his trilogy Sword of Honour, whose subject is the public and personal reverberations of the Second World War.

With apologies to Messrs. Mailer, Heller and even Pynchon, this is the finest work of fiction about that conflict. Following the wartime career of its sadly quixotic hero Guy Crouchback amid the antics of assorted brigadiers, rankers, politicians, socialites, partisans, wives and mistresses, Sword of Honour is a work whose scale and seriousness are offset by a remarkable lightness of texture. Its humor is both hard–it depicts the war as, among other things, a sordid jamboree of the smart set–and compassionate–the solemnly absurd Apthorpe is one of the richest and, in the end, most touching, comic characters in modern literature. As with his earlier works, Waugh’s jaundiced eye is trained on the flat detail of human folly, vanity and hypocrisy, but in this, his last novel, his scorn is modulated. Sword of Honour starts as a high comedy of army discipline and chicanery and maintains its ironic control even as it descends into a purgatorial world of military disaster–Waugh’s portrayal of the rout of the British forces on Crete is the finest depiction I’ve read of what Clausewitz called the fog of war–and of murderous and political treachery–Britain’s too-easy accommodation with communism, in both high government circles in Westminster and in the field in Yugoslavia represents for Waugh the final abandonment of honor. By its close, Sword of Honour has become a novel of formal melancholy. Rarely have comedy of manners and pathos been so artfully juxtaposed as in this ultimately elegiac, haunting, heartbreaking book.

With apologies to Messrs. Mailer, Heller and even Pynchon, this is the finest work of fiction about that conflict. Following the wartime career of its sadly quixotic hero Guy Crouchback amid the antics of assorted brigadiers, rankers, politicians, socialites, partisans, wives and mistresses, Sword of Honour is a work whose scale and seriousness are offset by a remarkable lightness of texture. Its humor is both hard–it depicts the war as, among other things, a sordid jamboree of the smart set–and compassionate–the solemnly absurd Apthorpe is one of the richest and, in the end, most touching, comic characters in modern literature. As with his earlier works, Waugh’s jaundiced eye is trained on the flat detail of human folly, vanity and hypocrisy, but in this, his last novel, his scorn is modulated. Sword of Honour starts as a high comedy of army discipline and chicanery and maintains its ironic control even as it descends into a purgatorial world of military disaster–Waugh’s portrayal of the rout of the British forces on Crete is the finest depiction I’ve read of what Clausewitz called the fog of war–and of murderous and political treachery–Britain’s too-easy accommodation with communism, in both high government circles in Westminster and in the field in Yugoslavia represents for Waugh the final abandonment of honor. By its close, Sword of Honour has become a novel of formal melancholy. Rarely have comedy of manners and pathos been so artfully juxtaposed as in this ultimately elegiac, haunting, heartbreaking book.

I’ll Take My Stand is a collection of essays written in 1930 by “Twelve Southerners,” including Allen Tate, John Crowe Ransom, Robert Penn Warren, Donald Davidson, Andrew Lytle and Stark Young, collectively known as the Agrarians. Its neglect is understandable– by contemporary standards its contributors’ attitudes toward black Southerners are at best paternalistic, and it excoriates a political economy and attendant culture that are now unassailable–but regrettable. The Agrarians’ is this century’s most eloquent home- grown condemnation of the destructive power of capitalism and the perils of unfettered individualism, of the separation of ownership from the control of property and of the destructive exploitation of nature. A plea to resist the allure of the market, I’ll Take My Stand defines and defends a tradition that is at once conservative and radical against the nationwide creation of a wage-dependent working class and of an atomistic, individualistic and impersonal society. Its cause–what Young characterized as “social existence rather than production, competition and barter”–was, of course, futile. It nevertheless constitutes, as such admirers as Christopher Basch and Wendell Berry have recognized, America’s most impressive critique of our national development, of liberalism and of the more disquieting features of the modern world. Only the most shallow reader can finish I’ll Take My Stand without a poignant sense of loss. *

- Juan Goytisolo

- Someone asked Nabokov the three novels of this century he preferred. His answer was: Ulysses, A la Recherche du Temps Perdu, and Petersburg by Andrei Bely. I agree with him. But whereas everyone knows the first two, Bely’s masterpiece is almost forgotten both in Russia and in the West.

- Noel Annan

-

E.M. Forster was a novelist in line from Jane Austen and George Eliot. Before World War I he wrote four novels pulverizing the assumptions of the genteel upper classes, their snobbery, their imperialism, the insensitivity and coarseness of the so-called public school code of manners. Then after the war he visited India and discovered that the tidy scheme of morality he had set against the narrow values of the English professional classes was inadequate. It could not take in the multitudinous life of the East. His moral vision no longer made any sense. Until then he believed that passion and money were the two things that moved people to act as they did. Now he saw that religion was as important. He still thought personal relations the most real things on the surface of the Earth, but rationality and affliction are not enough: loneliness–getting away from friends–is needed to deepen intimacy.

Today the stage is held by a generation of dazzling Indian novelists–Salman Rushdie, Vikram Seth, Anita Desai, Arundhati Roy– who have pushed A Passage To India into the wings. But it remains not merely a remarkable critique of imperialism but startling in its honesty. Forster declared that however enlightened, even affectionate, Englishmen might be, Indians would never accept them as equals until they got out of India. If he does not spare has own countrymen, neither does he sentimentalize Indians. India taught Forster that rationality is not the only key to life’s mystery.

- G. Cabrera Infante

-

The novella, rather than the novel, is a Spanish invention by the same man who wrote Don Quixote: Miguel de Cervantes. He called his novellas “exemplary novels” and claimed to be the first writer who wrote novellas in Spanish. Though the novella has not been widely cultivated in Spain, there are two examples written in this century that are more masterful than exemplary. They are two novellas of impossible love: Morel’s Invention by Adolfo Bioy Casares, and Valentin by Juan Gil-Albert. Bioy Casares is an Argentine writer; Gil-Albert is a Spaniard from Valencia.

Morel’s Invention (published in 1940) is the fantastic tale of a castaway who lands on an uncharted island, where he falls in love with a strange, beautiful woman he sees from afar until he discovers that she is a phantasm created by an amazing machine: the invention of the title. It is the best love story written in Spanish in this century, of which none other than Jorge Luis Borges said: “To classify it as perfect is neither an imprecision nor a hyperbole.”

Valentin is a story of homosexual love in Shakespeare’s time–on his stage even. Written underground in 1964 but published in Spain in 1974, it has never been translated into English, though it does for the Shakespearean stage more, much more than the spurious “Shakespeare in Love” about a heterosexual Shakespeare. Gil-Albert in his masterpiece shows that he knows all about Shakespeare and his stage and the so-called real life in the Elizabethan era.

Both books are tragedies of unrequited love.

- Marina Warner

- The imaginative enterprise of the Surrealists goes without saying. Though Andre Breton or Louis Aragon may not be widely read, they’re accepted as profoundly influencing a 20th century way of thinking and writing. Ideas about tapping into the unconscious, transfiguring ordinary life through dreaming and fantasy, accepting the happenstance of chance and coincidence have had far-reaching effects that are still with us (Paul Auster for one is unthinkable without them). The Surrealists’ fascination and praise of “primitive” cultures, of tribal masks, sculpture, costumes and customs–from Oceania, Africa and the Americas–famously helped direct the aesthetic of modern art. Yet Benjamin Peret, one of the founding members of the movement, is all but forgotten. An oracular poet, a militant who fought in the Spanish Civil War and was imprisoned by the Vichy government in 1940, he accepted the Mexican offer of sanctuary for political refugees in 1941; there, he attempted to do for Pre-Columbian literature what Picasso and others had done for the artifacts (the masks and the sculpture). He began collecting the scattered stories and beliefs of indigenous American peoples. The resulting Anthologie des mythes, legendes, et conles populaires d’Amerique (Anthology of Myths, Legends, and Popular Tales of America, Paris, 1960) was published after Peret’s death in 1959. It’s a vast, rich, surprising collection, which reconstitutes (re- members) a huge body of oral tales from Jesuit reports, explorers’ descriptions, ethnographic journals, in a dozen languages. Peret wrote that he had entered, as it were, the mind of a Hopi doll and found himself inside a marvelous chamber, whose walls gave way before him “like tall grasses parting at the passage of a wary wild beast . . . and I am inside, drawing down gleams of aurora borealis.”

- Paul Muldoon

- A book now almost forgotten, even in Ireland, is Heinrich Boll’s Irish Journal (Irisches Tagebuch), the German writer’s hilarious and heartwarming account of a visit to the country in the mid-1950s, when the Celtic Tiger looked more like a moth-eaten tabby. Boll recounts how, on the steamer across the Irish Sea, “the safety pin, that ancient Celtic clasp, had come into its own again,” which is just what one would hope for this sharp-witted little book.

- Ben Sonnenberg

-

A book I should like to see back in print is The Selected Works of Cesare Pavese (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1968). It comprises four of his nine novels in excellent translations by R.W. Flint: The Beach (a novella, 1942), The House on the Hill, Among Women Only, and The Devil in the Hills (all 1949). The book is a good introduction to an important writer of postwar Italy. Once internationally famous, now mostly overlooked, Pavese was the peer (and friend) of Natalia Ginzburg, Alberto Moravia and Elsa Morante. Their society had been destroyed by fascism, imprisonment, exile, poverty and war. Pavese was a prolific “neo-realist” for much of his short career. He gave us his native Turin and its environs during and after the war much as Leonardo Sciascia gave us his Palermo. Pavese’s work shows the influence of the English and American authors he translated (superbly, I understand): Defoe, Dickens and Melville, Joyce, Gertrude Stein and Faulkner.The works in Flint’s selection are romantic satires. They owe much to Pirandello in their tragicomic suspense, and in their intellectual fun they foreshadow Italo Calvino. Their recurrent images of rural roads and taverns and towns, all of them lonely and haunted, of the Piedmontese hills and rivers form a suitable background for Pavese’s characters. His typical protagonist, whether male or female, is almost always an image of Pavese himself: heartbroken, voluble, stubborn and tortured by philosophical doubts. His character, heartbreak, torture and doubts are unforgettably expressed in his posthumous diaries, The Burning Brand (1961), translated by A.E. Murch.

Pavese ended his life in 1950 at the age of 42. 1 started reading him soon after that when I was in my 20s. I remember a different Pavese from the one I find today. His novels seem deeper to me now and much more interesting. Among Women Only and The House on the Hill are magnificent entertainments. Together with his last novel, Moon and the Bonfire (1950), they reward being read again at the turn of the century.

- Frederic Morton

- For me the most neglected work by a well-known author is Arthur Schnitzler’s novella Leutnant Guetl published at the very start of our century in 1900. The story uses the stream-of-consciousness technique (years before Joyce) to light up through a lieutenant’s psyche Austria’s troubled fin de siecle. Also suffering from what is to me outrageous neglect is Dudley Young’s Origins of the Sacred, a marvelously imaginative and ecumenically knowledgeable meditation on the religious instinct, published in the United States in 1991.

- J.D. McClatchy

- Our century has forgotten many writers, and ambushed a few as well. Take Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, for instance. The 11 volumes of his Collected Works published in 1886 and read devotedly through the early decades of this century, were a monument to an extraordinary career. At the time of his death, he was the most widely read and beloved poet in the world. His 75th birthday was a national holiday. Lincoln’s eyes welled with tears when a Longfellow poem was recited. Queen Victoria invited him to tea. His dates (1807- 1882) virtually span the 19th century. His father had been a friend of George Washington; one of the last visitors to Craigie House–Longfellow’s home in Cambridge, long since a pilgrimage site–was Oscar Wilde. But for all his fame, the Modernist braves shot him down like a dazed buffalo. They despised his moralizing sentimentality and smooth, hearthside authority. Their triumph was our loss. No, he was not a great poet–not a Whitman or Dickinson. But more often than you’d think, he can be an astonishing one. He made American poetry less naive and local by incorporating European models. His prosodic innovations were virtuosic. And he created a kind of American mythology–Evangeline in the forest primeval, Hiawatha by the shores of Gitchee Gumee, the midnight ride of Paul Revere, the wreck of the Hesperus, the village blacksmith under the spreading chestnut tree, the strange courtship of Miles Standish, the maiden Priscilla and the hesitant John Alden. Was my generation of schoolchildren the last who memorized these poems? They had–like poems by Robert Frost in his day–sunk deep into the national subconscious. Though today his name goes unmentioned and his poems unread, I suspect they are still there, on a back shelf of every reader’s memory. Dusted off, they would surprise you: Their images can still startle, their narratives still enthrall.

- Thom Gunn

- The modernist attack on Arnold Bennett has been pretty successful. His books, which crowded the shelves of bookstores in my youth, are nowadays hard to find. Yet his best two novels are far more satisfactory as records of what it is to be human than Virginia Woolf’s best two, which seem snobbish and fluttery by comparison. She never retracted her attack on Bennett, but Ezra Pound, at least, later qualified his dismissal of Bennett when he “finally got round to reading” The Old Wives’ Tale which is surely a neglected masterpiece if ever there was one. To it I would add Bennett’s Riceyman Steps which I came to only this year. The great virtue of these two novels is in their detailed and sympathetic treatment of people who are largely unsympathetic: Bennett is humane and sturdy, witty and delicate, never boring, never condescending and never superficial. Read them!

- Michael Henry Heim

- If you’re interested in the mark that communism, especially its Russian variant, has left on the century, and if you’ve read Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago and Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita on the cataclysmic, all but cosmic aspects of the Russian Revolution, you might want to have a look at the down-to-earth anatomy of everyday Soviet-style intrigue in Yuri Trifonov’s House on the Embankment (1976). The plot centers on a denunciation, and because the denouncer is a graduate student and the denounced his advisor (and, to make matters more piquant, his potential father-in-law), the novel may at first glance seem analogous to a David Lodge campus novel. But Trifonov’s tale is a grim one–all the more so because 25 years earlier he had written an archetypal Socialist Realist novel called Students in which he depicts the denunciation of a professor as the most natural thing in the world. If you’ve read Solzhenitsyn’s naturalistic account of the Gulag, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, you might want to try Georgi Vladimov’s Faithful Ruslan (1974 in samizdat, but not published officially until the Soviet Union was in its death throes), which views the same labor camp world from the point of view of a guard dog. Clearly allegorical- -the Gulag stands for Soviet society ideally regulated, the dog for Soviet man ideally trained–the novel treats issues of obedience and responsibility that go beyond the time and place it evokes so powerfully. Both works are well represented in English by Michael Glenny’s fine translations.

- Cynthia Ozick

-

Rudyard Kipling, who died in 1937, is incontrovertibly one of the most renowned writers of the early 20th century. Paradoxically, despite his name’s irrepressible familiarity, he is also among the most eclipsed. There may still be imaginatively wise children who prefer the enchantments of any page of Just So Stories (adorned with Kipling’s own magical illustrations and whimsical verses) to the crude smatterings of the film cartoons–but Kipling is vastly more than a children’s treasure. All the same, serious readers long ago relinquished him: Who now speaks of Kipling? The reason is partly contemporary political condemnation–enlightened post-colonial disdain– and partly contemporary literary prejudice. Together with Joseph Conrad, Kipling carries the opprobrium of empire, “the white man’s burden,” though his lavish Indian stories are often sympathetically and vividly understanding of both Hindu and Muslim. And he is ignored on the literary side because in the period of Joyce’s blooming, Kipling’s prose declined to be tricked out with the obvious involutions of modernism. Unlike Joyce, James and Woolf, he gets at the interiors of his characters by boring inward from the rind. Yet he writes the most inventive, the most idiosyncratic, the most scrupulously surreal English sentences of the century (next to which Woolf’s are commonplace).Kipling’s late stories–“The Wish House” (in ingenious dialect), “Dayspring Mishandled,” “Mary Postgate,” “The Gardener,” “The Eye of Allah,” “Baa Baa Black Sheep” (an autobiographical revelation), “Mrs. Bathhurst” and others–form a compact body of some of the strongest fiction of the last hundred years. Kipling’s wizardry for setting language on its ear, his insight into every variety of humanity, his zest for science, for ghosts, for crowds, for countryside, cast him as the century’s master of what we nowadays call “diversity”; no strand of civilization escapes his worldly genius. Certainly the neglect of these sly, penetrating, ironically turned tales diminishes our legacy of Story.

- Margaret Atwood

-

Doctor Glas a short, astonishing novel by Hjalmar Soderberg, was first published in Sweden in 1905 and caused a scandal because of its handling of sex and death, not to mention abortion and euthanasia. The narrator is Doctor Glas, whose journal we read over his shoulder as he composes it. His is the unnervingly familiar voice we follow in its reflections, its lyrical praises or splenetic denunciations, its prevarications, its boredoms, its wistfulness. A romantic idealist afflicted with fin de siecle malaise, unable to fall in love except with women who love someone else, he offers both the candid transparency and the narcissism his surname suggests.

It’s no accident that his second name is Gabriel, for he’s tempted to play Angel of Life to a beautiful woman who begs for his help. Ignorant of the facts of marriage, she’s allowed herself to be pawned off on a “respectable” but loathsome clergyman. The help she wants from Glas is freedom from this troll’s sexual attentions, doubly repugnant because she’s having an affair with another man. Angels can of course be angels of death as well as of life, and doctors are conveniently situated for this role. The ensuing plot is a cunning triple-tied knot.

Doctor Glas is deeply unsettling, in the way certain dreams are- -or certain films by Ingmar Bergman, who must have read it. It moves from the sordid to the banal to the anxiously surreal to the visionary, with economy and impressive style. A few years earlier and it would never have been published; a few years later, and it would have been dubbed a forerunner of stream-of-consciousness. It occurs on the cusp of our century, opening doors we’ve been opening ever since.

- Susan Sontag

- Of forgotten classics of 20th century fiction, there is surely no end of candidates. Indeed, as a friend who may have spent too much time hanging out with French people used to exclaim, “Let me not commence!” But I will. May I mention three, maybe four, among many favorites? Two from the beginning of our century, Natsume Soseki’s And Then (1909) and Theodore Dreiser’s Jennie Gerhardt (1911), and one published (in Hungarian) at the start of the century’s last quarter, Imre Kertesz’ Fateless (1975). I’ve never understood how Soseki (1876-1916), the first great Japanese novelist, could be virtually unknown to English-language readers; all of his late books, with their splendidly self-aware protagonists overwhelmed by the paradoxes of modernity, are wonderful. (And Then was translated by Norma Field; I can’t resist also mentioning Light and Darkness, his last, never-completed novel, translated by V.H. Viglielmo.) Jennie Gerhardt Dreiser’s almost forgotten second novel about a long-term common-law marriage–it comes after Sister Carrie and before An American Tragedy–is the novel of his I most admire. (Try to read it as Dreiser wrote it; an unexpurgated Jennie Gerhardt had to wait until 1992 to be published, by the University of Pennsylvania Press.) Fateless by Kertesz (b. 1929), translated by Christopher C. and Katharina M. Wilson, is an astounding, utterly original, supremely upsetting short novel about the Holocaust. Books for grownups.

- Milan Kundera

- Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities evidences a penetrating, fascinating, entrancing intelligence. And withal a true novel: It is through his characters’ situations that Musil achieves a matchless existential diagnosis of our century. Everything is there: the rule of a technology beyond human control, turning mankind into statistical figures; omnipresent bureaucracy seizing hold of lives; speed, idolized as a supreme value; the previous century’s romanticism transformed into ubiquitous kitsch; exaggerated sympathy for criminals as a mystical expression of the religion of human rights (Clarisse’s passion for Moosbrugger); infantophilia and infantocracy, whose stupid smile casts light on the callousness of the technological era.

- Mindy Aloff

-

A classic: an efficient and timelessly interesting construction that lends an illusion of sense to an irrational world and leads its perpetually astonished audience both backward and forward within the tradition of its expressive medium.

A neglected classic: A book one wishes were still in print.

Example No. 1: The Reader Over Your Shoulder: A Handbook for Writers of English Prose, by Robert Graves and Alan Hodge. Second edition, revised and abridged by the authors (rare): New York: Random House, 1971. First edition (rarer and, by report, filled with even funnier examples of wayward writing): New York: Macmillan, 1943. Some strong medicine here; not recommended for artistes:

“As a rule, the best English is written by people without literary pretensions, who have responsible executive jobs in which the use of official language is not compulsory; and, as a rule, the better at their jobs they are, the better they write.”

Example No. 2: Ballet 104 photographs by Alexey Brodovitch, with a radiant introductory essay (never anthologized) by Edwin Denby, New York: J.J. Augustin, 1945. Blurry, urgent, wide, black- and-white performance photographs, shot from the wings, of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. In the midst of this battlefield reporting, apparently haphazard details–like the stage light that reads as the full moon over Danilova in “Swan Lake”–suggest a composure that does not meet the eye. Rarely has the theatrical dimension of ballet looked more glamorous or alive to a camera.

- Elmore Leonard

- I have to go with Richard Bissell (1913-1977) as an American writer who is sorely neglected–emphasis on American. He wrote High Water and A Stretch on the River among others, novels set on the Mississippi River. Bissell is the only American writer since Mark Twain, who wasn’t bad either, with a license to pilot river boats. He also wrote 7-1/2 Cents which was adapted as the musical “The Pajama Game.” I learned three-quarters of what I know about writing from reading Richard Bissell, God bless him.

- John Le Carre

-

If I had to name one 20th century novel that has somehow missed out on the popular acclaim it deserves, I’d go for Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier. It does for the fragile male psyche what Anna Karenina does for the women.

Lower down the literary ladder, let me single out Geoffrey Household’s Rogue Male the unsung precursor of such novels as The Day of the Jackal. It was published, I believe, on the day World War II broke out, which was in all senses bad luck, since it was about an English gent who thought it would be fun to assassinate Hitler. The film, with James Mason in the lead, did little.

- Alain de Botton

- My favorite forgotten book of the 20th century is Cyril Connolly’s The Unquiet Grave. It’s a seductive mixture of diary, common-place book, essay, travelogue and memoir–arranged in loose paragraphs, in which Connolly gives us his views on women, religion, death, seduction, infatuation and literature. The thoughts are wise, dark and beautifully modeled, with the balance of the best French aphorisms. For example: “There is no fury like an ex-wife searching for a new lover,” ‘No one over thirty-five is worth meeting who has not something to teach us–something more than we could learn from ourselves, from a book.” The charm of the book lies in the narrator’s mischievous, melancholy tone as he shifts between the sublime and the banal: “To sit late in a restaurant (especially when one has to pay the bill) is particularly conducive to angst, which does not affect us after snacks taken in an armchair with a book. Angst is an awareness of the waste of our time and ability, such as may be witnessed among people kept waiting by a hairdresser.”

The Unquiet Grave is a book about a thousand things, held together by the intelligence, candor and humor of the author. I’d find it hard to pursue a friendship with anyone who didn’t have any sympathy for it–and hard to hate someone who did.