This is a guest post by Stephen Bloomfield

Edwin Brock only wrote one novel.

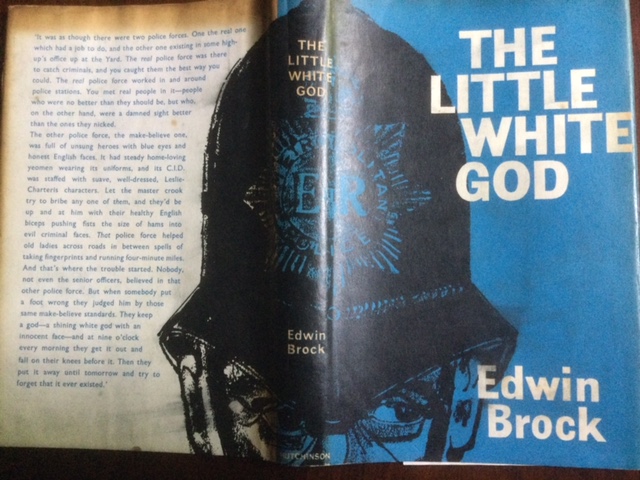

In 1962, after eight years as a Police Constable 258 of the Metropolitan Police between 1951 and 1959, he published The Little White God, an early example of what later came to be called a ‘police procedural’ novel.

Why then, if he only published one novel, is he of any interest?

First, because Brock went on to publish some very good poetry – quite a lot of it – and two of his poems are among the most anthologized of the twentieth century. So, the novel is an interesting waystation on the path of his development.

Second, because the novel is worth something in its own right. After a shaky few opening paragraphs, it develops strongly and gives an intriguing view of an unusual episode in an ordinary copper’s life in a suburban division of ‘the Met’ during the post-war years. It describes the perpetual battle between an efficient police force and a justice system striving for fairness; it lays bare, very vividly, the universal battle between the ‘doers’ and the paper-shufflers in any organisation; and it analyses, softly and subtly as it goes along, some deep moral issues about right and wrong.

Brock was born in 1927 to a working-class family in the middle-class suburb of Dulwich in South London. Books were apparently few in the Brock household and the atmosphere was occasionally ‘turbulent’. Brock won a scholarship to the local grammar school but left after completing his school certificate, the family lacking the funds or ambition to push his education any further.

Too young to be ‘called up’ in the war years, he completed his National Service in the Royal Navy and ended up in Hong Kong waiting to be “demobbed’ in 1947. Listless and bored, Brock began to read anything he could get his hands on at the NAAFI (the British servicemen’s welfare organisation) library and, finally, was reduced to borrowing a book of poetry.

This proved to be the opening of a door. After reading the paperback poems, Brock knew he wanted to write. As his fellow poet, obituarist and friend, Anthony Thwaite, would put it later, Brock thought that most activity is a means of defining oneself; and for Brock, poetry was the best means, of doing that.

After leaving the Royal Navy, Brock secured a job as a trade journalist and used the free time it afforded to write poetry, most unpublished, as a way of developing his proficiency and style. He gradually accumulated publication credits in small, literary poetry magazines of the time. He married in 1949 and, with a young family needing the regularity and the prospect of increasing income, two years later he joined the Met. He continued to write poetry.

His break came when the editor of the Times Literary Supplement published a few of his poems, accepted on their merits, without any knowledge of who or what the author was. The TLS is famously intellectual, so publication caused quite a stir in literary circles, when his identity as a working policeman with no more than a grammar school education became known.

This led to a brief flash of celebrity. when a journalist from the Daily Express interviewed him and the paper’s editor gave the resulting piece a full-page splash. Far from the reprimand expected for giving an unauthorised interview,– which appeared in the Daily Express as ‘PC258 CONFESSES I’M A POET –THE THINGS HE THINKS UP AS HE POUNDS THE BEAT’ – Brock’s revelation was received tolerantly.

In 1959, he left the police and joined the advertising firm of Mather and Crowther as a copywriter. It was here that he mined his experiences “pounding the beat”, as the Express had it, and produced The Little White God. The novel was published by the prestigious firm of Hutchinson (no, unfortunately not Constable). The Little White God was never published in the USA, despite the American readerships’ appetite for police novels (although British readers were happy to lap up American crime fiction in all its forms) possibly because of some of the unfamiliarity of the context and the commercial risk associated with a first novel.

The Little White God describes the downfall of Detective Constable Mike Weller, a (generally) good and conscientious policemen, who, like most of his colleagues, is tuned in to the rhythms of the streets he patrols. He is an alpha male without being macho; aware that only a thin line of fate separates him as a policeman from many of the criminals he brushes up against, coming as they did from the same background. They drink at the same pubs, live in the same areas, marry women from the same background– and accept the rules that police, crooks, the courts and prison dance to in the game of justice in post-war Britain. But the men who join the police become “Little White Gods” and their downfall, if it comes, is even harder.

‘Like most of his colleagues’ does not mean all of them, though. Weller has the misfortune to report to a superior officer who does not have the tolerance Brock himself experienced as a PC. Although happily married, Weller cannot resist having an affair with the wife of a small-time criminal he has arrested for ‘sus” — suspicion of attempting to break into a locked shop. The relative triviality of this offence and the three-month sentence it attracts is crucial to the timing of Mike and Rosie’s affair. It is a criticism later levelled at Weller that he could have “fitted him up” better by charging him with by going equipped for breaking and entering.

The affair develops into much more than Weller anticipates. The crook seeks revenge by putting stolen goods in the shed at the back of Weller’s house and then writing anonymously to the Station Sergeant at Weller’s police station. Through force of circumstances, the sergeant is forced to report the anonymous letter to the new senior officer in charge of the station who is out to make an impact. The officer, in turn, outwits his divisional chief in a trial of procedural strength and Weller is the victim of the struggle.

The Little White God is structured in two parts, the first being the development of the affair and the receipt of the letter, the second what happens afterwards. It is very definitely a book of two halves in terms of writing style, as well. While the second half is tight and falls very much into the category of a ‘police procedural’ the first half is, initially, slightly over-written:

Outside the Court, the sun was doing its best but making heavy weather of it. It would look out of the clouds for a minute or two and then the sky would shut up to give the wind a chance. Round the corner it blew as though it were coming straight from Siberia. It was the kind of wind that seemed to make your clothing feel transparent.

And later:

On top of the bus the wind came at them like a four-ale bar pug – all rush and no science – until they turned a corner and it retired out of breath.

“Transparent”? “Four-ale bar pug”? Apart from the confusing analogies, Brock is obviously in poet mode in starting the book.

But the narrative soon gathers its stride. The descriptions of South London suburbia and its residents becomes more fluent and less contrived, more based in the reality of Brock’s experience — and Mike Weller’s fate:

It was as if there were two police forces. One was the real one which caught criminals and the other was the one that existed in some high-up’s office at the Yard. The real force was there to catch criminals and you caught them the best way you could. You knew who they were and if you couldn’t get them down according to Judge’s Rules, you got them down in your own way. Mike could see nothing wrong with that. He was paid to catch thieves and he bloody-well caught them.

But it is this attitude that proves to be Mike’s undoing. His ambitious station commander has aspirations for a position at the Yard and has the mindset to go with it. In his eyes, Weller’s having an affair with a criminal’s wife is the greater crime and, thwarted at not being able to take Mike out ‘fairly’, he ensures that Weller pays for his indiscretion. Brock keeps the reader uncertain about Weller’s fate almost to the end of the book.

Weller is demoted from detective to beat policeman and subjected to all the petty and largely mindless administrative procedures that the lowest on the pecking order have to put up with. He loses his wife and his marriage, probably keeps the love of Rosie but certainly loses his livelihood in a grand gesture of resignation.

To the British reading public at the time, this unsentimental insider’s view of the police would have been a marked change from the prevailing conventions. At the time, the most famous fictitious British policemen was Dixon of Dock Green — an avuncular sergeant close to retirement age who had seen it all and who recounted police-station stories of the “it’s a fair cop, guv” type on television on Saturday evenings. The revolutionary and grittier Z Cars (which influenced many later British police series) was just about entering its stride but the cynical tone of Line of Duty and its Chief Inspector Hastings of AC12 (who would become a British cultural icon in his own right), with its unremitting focus on internal corruption, would have to wait a generation or more of profound social change.

Despite his upbringing and background, Brock is only hit-and-miss when it came to the novel’s dialogue. Conversations in the workplace and between policemen are clear, unstilted, direct but with the necessary amount of ellipsis of ordinary dialogue between people with shared conventions and background. Conversations between the male and female characters are less convincing. Aside from using the word “gel” (hard ‘g’) to stand for the South Londoner’s catch-all term for a woman, Brock offers few other stylistic clues to accent or educational background in the male-female exchanges. The 1950s lower classes in Peckham are suspiciously precise about grammar and syntax — especially Weller’s paramour Rosie.

But this is carping criticism. The novel is not dialogue-dependent for its momentum, being as much an examination of social ideas, cultural customs and a dissection of moral attitudes.

What then of Brock after The Little White God? In his first collection published in the US, Invisibility is the Art of Survival, the jacket biographical sketch states:

Born in London in 1927, Brock says he has spent the subsequent years waiting for something to happen, occupying his time as a sailor, journalist, policeman, and adman, in that order. Yet none of this, he feels, has touched him, “except with a fine patina of invisibility.” Poetry, however, is for him an act of self-definition “which sometimes goes so deep that you become what you have defined. And this,” he adds, “is the nearest thing to an activity I have yet found.” Thus in addition to being poetry editor of Ambit, Brock has published several volumes of his own. His first, An Attempt at Exorcism, was brought out in 1959, and was followed over the next decade by A Family Affair, With Love from Judas, a large selection in Penguin Modern Poets 8, and A Cold Day at the Zoo. Confronted with his work, American readers will agree with the critic Alan Pryce-Jones that Brock has written “some of the most observant and compassionate poems of our time–poems, moreover, in which the poet keeps his feet on the ground as skilfully as his head in the air.”

(Alan Pryce-Jones was the editor of the TLS who first spotted Brock’s poetry.)

The reviews that the Little White God received may also have contributed to Brock not writing another novel. The Times reviewer praised the novel’s “blatantly unvarnished authenticity” but Simon Raven (another now-neglected novelist) in The Spectator damned it with faint praise by saying that the documentary account was “smartly done in its way”. An anonymous reviewer in the TLS said that “the documentary element is the most valuable … but does not go deep…” while having “… sufficient vitality to complement the other more important side of the novel”. But perhaps what might have sealed the fate of further novelistic adventures was Anthony Burgess’s (rather unkind) conclusion in The Observer that “Brock is capable of better than” a documentary.

Brock probably got something out of his system with The Little White God. It was written at the same time as James Barlow, Allan Sillitoe, Stan Barstow, John Braine, John Osborne, and the loose grouping that became known as the ‘Angry Young Men’ were active. So it was in good radical company. But Brock maintained that it was poetry that helped him to define himself, so the success he began to have with that – he joined the editorial staff of the quarterly literary magazine Ambit in 1960 – probably meant he chose to concentrate on the strong suit of poetry rather than risk further half-hearted praise with novels.

Like most poets – and many prose authors – Brock could not make a living out of his writing alone, so for 30 years he stayed in advertising at Mather and Crowther, rising up the company, through its mergers, to end as a director and originating the famous “No FT. No comment.” slogan along the way. He edited the poetry section of Ambit for nearly four decades (1960-97), rubbing shoulders with the likes of J. G. Ballard, Eduardo Paolozzi and Carol Ann Duffy.

The Little White God was an early starter in the field of the British police procedural. The description of the investigation by the ‘rubber-heelers’ –Scotland Yard’s internal affairs men, who are the catalysts of Weller’s demise – is, as the publisher noted, documentary in style and as different from the aristocratic, amateur detective novels beloved of the Golden Age as chalk from cheese. Changing social attitudes from the war and then post-war austerity did away with that.

Those who only know Brock’s poetry will find it an interesting read since it fits well with his early poetical works and fills a gap, demonstrating the importance of experience in his writing. It is a deceptively angry book — angry at the frustration of advancement because of artificial barriers; impatient with rule-bound satraps who value mindless procedure above sensible outcome: hinting at the beginnings of rebellion.

Those who are fresh to Brock may well find that the novel is an enticing stepping stone to a poet of considerable talent in encapsulating the significance to the individual of common hurts. It was only as he got older that he got mellower. His initial works were partly autobiographical, coloured by the unhappiness of his first marriage. Later they became broader and less personal – more infused, paradoxically, like The Little White God –with the experience of ordinary people of the hurts inflicted by the world. Two of his poems– “Five Ways to Kill a Man” and “Song of the Battery Hen” — were particularly popular with compilers of anthologies.

As an ex-journalist and writer of academic texts, Stephen Bloomfield is baffled why so many excellent books become neglected.