· Excerpt

· Editor’s Comments

· Review

· Find Out More

· Locate a Copy

Excerpt

In the early years of his reign the King lived mainly at the Tuilleries in Paris, but in 1722 he moved to Versailles. Officially he occupied the gorgeous rooms which his great-grandfather had tenanted and slept in the monumental bed in which the Great King had died. But in fact these majestic apartments were too grand and cold for a man who, however promiscuous may have been his love-affairs, was essentially of a domestic temperament. He thus, with the help of ingenious architects, constructed a suite of private rooms communicating by a secret staircase with the state apartments. There were in the first place what were called les cabinets, namely, bedroom, bathroom, dining room, library, and study looking out into an interior courtyard. Above them was an even more private suite, known as les petits appartements, situated as a penthouse under the leads and surmounted by a private roof garden containing macaws, parrots, canaries, monkeys, and pleached trees of box, or myrtle or bay in blue and white tubs. It was here that the King would play with his children or exercise his fat angora cat.

The rigor and symbolism of court etiquette can be assessed by the strange fact that, although it was in his private flate that the King flirted and pretended to work, the state apartments below retained their old hierographical significance. Louis XV, like his great-grandfather, would undergo the slow, elaborate, and unbearably pompous parade of going to bed. Still would the dukes and marquises compete with each other to be accorded the honor of holding the candle or helping the King to get out of his shirt. When the last rites had been accomplished, when the carved and gilded barrier that separated the bed from the rest of the room had been ceremoniously closed, when the last courtier, bowing profoundly, had backed out of the bedroom into the adjoining oeil-de-boeuf, then Louis XV would leap out of bed again, put on his dressing gown, and, accompanied by a personal page carrying a light, would skip up the secret staircase and slip into his own comfortable bed in his own comfortable room. Then in the morning the ceremony had again to be performed in reverse. It never seems to have occurred, to either Louis XV, his family, or his courtiers that these cumbrous parades were absurdly unreal. The monarch was King by divine right, and his accustomed actions must be distinguished from those of ordinary mortals, as it were liturgically.

Editor’s Comments

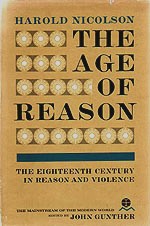

The Age of Reason was the first of a half-dozen or so books in a series published by Doubleday in the early 1960s. Edited by the veteran reporter John Gunther, author of the popular “Inside” books of the 1940s and 1950s, the series had the impressive title of “The Mainstream of the Modern World.” Although works of history, the books were all written by authors better known for fiction (Alec Waugh), reportage (Edmond Taylor), or miscellany (Nicolson), and all focused more on personalities than movements, politics, and larger issues.

The Age of Reason was the first of a half-dozen or so books in a series published by Doubleday in the early 1960s. Edited by the veteran reporter John Gunther, author of the popular “Inside” books of the 1940s and 1950s, the series had the impressive title of “The Mainstream of the Modern World.” Although works of history, the books were all written by authors better known for fiction (Alec Waugh), reportage (Edmond Taylor), or miscellany (Nicolson), and all focused more on personalities than movements, politics, and larger issues.

Although Nicolson declares his subtitle to be, “A study of the mutability of ideas and the variety of human temperament,” his emphasis is on the latter. As with his classic, The Congress of Vienna, Nicolson is an unapologetic popular historian, in the vein of Andre Maurois, Stefan Zweig, and others of his generation, writers who never felt their amateur status disqualified them from using history as a canvas of characters every bit as intriguing as any they might make up.

Of the twenty-one chapters in the book, nineteen are miniatures of a representative figure from the 18th century. Most are very well known: Peter the Great, Jonathan Swift, Voltaire, Samuel Johnson, Benjamin Franklin, Rousseau. Making no claims to scholarship, Nicolson is unlikely to have uncovered any remarkable new material about them, so one could ask what makes such a book worth a bother forty-plus years after it was written.

The answer is simple: because it’s superbly entertaining. Nicolson gives us the basic facts of each life, but these are just a frame within which he weaves a tapestry of observations and anecdotes. Most of his material comes from the letters and memoirs of contemporaries: other historians are absent from the text. What doesn’t come first-hand sources comes instead from Nicolson’s keen eye for character and decades of experience in politics and diplomacy.

“Reason,” he quotes Herbert Read in his introduction, “is a very difficult word to use without confusion.” Nicolson acknowledges his skeptical view of the aspirations held out for reasoned discourse and rational thinking during the 18th century. We learn relatively little about the philosophical ideas any figure held or propounded, except as theory reveals something of the man who has it.

Instead, we learn of the merits and faults of each man and woman, of their eccentric habits and money problems, of their vanities and miseries. And we find out things more sober history books leave out. Take the opening of the chapter on Peter the Great, for example:

Walking in the royal park at Brussels, the inquiring traveler, if he diverge but a few yards from the graveled alleys of pleached lime, will come across a hollow among the shrubberies which is now used as a midden in which the gathered leaves are rotted down for leaf mold. In this declivity there is a small stone bearing a Latin inscription. It tells the traveler that on this spot the Duke of Muscovy, having drunk heavily, was violently sick. What is interesting about this memorial is that the Belgians at that date should have regarded the public vomiting of a reigning, even if barbarous, prince as so odd as to merit being recorded for posterity.

Considering how exhaustively documented the lives of most of his characters have been, it’s striking how often Nicolson introduces something like this–odd, trivial perhaps, but telling. As another example, take the ending of his chapter on Tom Paine:

William Cobbett … was shocked by the fact that the godfather of the United States should be shunned by all decent Americans. He therefore exhumed Paine’s body from the graveyard at New Rochelle and brought it back with him to Liverpool. For many years Cobbett preserved Paine’s skeleton in his house at Botley in Hampshire and on his death he bequeathed it to his son. The son, shortly afterward, went bankrupt and his possessions were sold by auction. Nobody has discovered who bought the bones of Paine. They have disappeared. And his works, which at the time created so prodigious an effect, are today unread.

This anecdote manages to be bizarre, tragic, and symbolic at the same time, which illustrates how, for all the novelty of the facts that Nicolson digs up, he never chooses them for novelty alone.

His lack of scholarly ambitions also allows Nicolson to inject his opinions where he feels the judgment is deserved. Thus, of Grand Duke Peter, husband of Catherine the Great, he writes, “He possessed a childish character, an incurable taste for low company, marked aversion from any form of study, and a violent temper. If not a certifiable lunatic, he was certainly a clinical specimen of arrested development.” After crediting Joseph Addison with “spreading to many dull and unenlightened homes the blessed habit of reading,” he passes a harsh sentence: “Addison’s complacency and optimism are as insipid as a vanilla puff.”

Such subjectivity is refreshing when dealing with historical figures. In too many works of history, maintaining the illusion of objectivity becomes an excuse for suppressing all sense of the writer’s own character. In Harold Nicolson, the Age of Reason had a chronicler with the erudition to deal with a broad and diverse span of time, ideas, and people with ease and skill, the political experience to make shrewd judgments of men, and the confidence to speak his opinions bluntly. The result is a tremendously enjoyable and satisfying work of history.

Review

- · Time magazine, 5 May 1961

- The age was often out of character but never out of characters. That is what fascinates Harold Nicolson, who scants history for personality, and arranges his book as a gallery of portraits bathed in the warm glow of idiosyncrasy rather than the cold light of 100% accuracy. The result is an “entertainment” written in the witty and amusing fashion of a male Nancy Mitford.

Find Out More

- Wikipedia entry on Harold Nicolson

- Review of Norman Rose’s biography of Nicolson in the Sunday Times:

” He was a rabid snob and a squirming snake-pit of prejudice, without even the intelligence to realise that other people were as human as himself…. Harold’s homosexuality, and the dangers it incurred, clearly instilled in him a habit of watchfulness. His writing hits off mannerisms, clothes and gestures unerringly.” - Portrait of a Marriage, the best-selling account of Nicolson’s marriage to Vita Sackville-West written by their son, Nigel.

- Note on The Age of Reason from a 2001 course on “Restoration and Eighteenth Century Poetry and Prose” from St. Thomas University, Canada.

- Other volumes in the “Mainstreams of the Modern World” series:

- China Only Yesterday: 1850-1950, a Century of Change, by Emily Hahn

- Eternal France: A History of France 1789-1944, by Norah Lofts

- The Fall of the Dynasties: The collapse of the Old Order, 1905-1922, by Edmond Taylor

- A Family of Islands: A History of the West Indies from 1492 to 1898, by Alec Waugh

- The Spanish Centuries: A Narrative History of Spain from Ferdinand and Isabella to Franco, by Alan Lloyd

- The Survival of Scotland;: A new history of Scotland from Roman times to the present day, by Eric Linklater

Locate a Copy

In Print?

Search for it at Amazon.com: The Age of Reason

Out of Print?

Search for it via AddAll.com: The Age of Reason

Brooks Peters added the following biographical information, along with a photo of Jane White, from the dust jacket of

Brooks Peters added the following biographical information, along with a photo of Jane White, from the dust jacket of  On the rare occasions when I’m back in the U.S., I always try to take time to stop by a public library and do some browsing through back issues of

On the rare occasions when I’m back in the U.S., I always try to take time to stop by a public library and do some browsing through back issues of