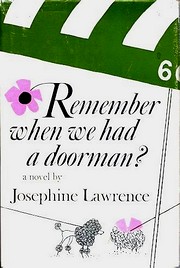

“Do you remember when we had a doorman?” is the stock question asked by the older tenants, whose occupancy dates back to the golden days when we had not only a doorman, but adequately uniformed elevator attendants and a handy man who could paint and repair, and even build simple furnishings such as bookcases. Above all, we remind each other in these nostalgic outbursts, we had a competent superintendent.

Remember When We Had a Doorman?

Remember When We Had a Doorman? is set in a Manhattan apartment building that’s seen better days. Most of its residents are retired or in their last working days, although there are enough young people to keep the gossip flourishing: “The elderly and retired, as the magazines (read mostly by the young) solemnly point out, have few resources and must depend for diversion upon–well, upon putting their wrinkled noses into other people’s business.”

One of the older women in the building is Holly Berry, Lawrence’s narrator. Holly makes a little money on the side as a dog walker, which keeps her in regular circulation throughout the halls and makes her an ideal observer for the many little dramas that play out over the 5-6 months covered in the novel. By the time she wrote Doorman, Lawrence had long since mastered the technical craft of fiction, and one of the more impressive aspects of this books is the size of the cast she manages–easily over 50 characters are introduced in the course of 170-some pages. Yet every one is provided with a certain amount of personality: Nicky, the lazy and incompetent new super; Mrs. Gilmore, for whom diet is the answer to all life’s problems; Aunt Sarah Turner, who arrives to put things to order when her niece’s husband proves a lush; Wilbur, the song-writing elevator man.

Lawrence was never considered a great writer, but the one thing critics consistently acknowledged over the course of 40-plus years she published novels was her feel for the real problems of working-class people. Years Are So Long (1934) was about the problem of housing for the elderly in the days before Social Security; If I Have Four Apples

(1935) was about people struggling to keep up with installment plans–the 30s equivalent to credit cards. Even a lesser work like I Am In Urgent Need of Advice

dealt with the confusions of a sexually-maturing teenager.

No one in Remember When We Had a Doorman?–with the possible exception of Oliver Locke, rumored to be one of the building’s owners, who holes up with mountains of old newspapers–is living on easy street. Those who work worry about making it when they retire; those who are retired worry about keeping up with rising grocery bills. And age is taking its toll:

It happened that this evening was the date of the semiannual “gala” evening of the bridge club to which I’ve belonged for more than thirty years. Time has effected changes. Where once we were eight couples, now we are eight widows. Once, the twice-a-year celebration meant dinner in one of the large restaurants and an evening at the theater; now, by common consent, we dine in a neighborhood restaurant and go to the movies, preferably one near at hand. But we do not, as Evie Keith says so firmly, accept the label of “senior citizens.” The trouble is, no one else we knows we reject it.

Remember When We Had a Doorman? was Josephine Lawrence’s 30th of 33 adult novels and somewhere around her 120th book if you include her many series of childrens’ books (“Brother and Sister,” “Betty Gordon,” “Elizabeth Ann,” etc.). Lawrence also wrote childrens’ and advice columns for the Newark Sunday Call for nearly 60 years and several drama series in the early years of radio. She started as a working woman back when that was still relatively rare and kept at it for longer than most of us will.

I found Remember When We Had a Doorman? remarkably fresh, entertaining, and grounded in unshakable common sense. It encourages me to seek out more of her work.

You can find out more about Lawrence’s life and books on Deidre Johnson ‘s comprehensive website devoted to childrens’ book series of the 19th and 20th century.

It’s a real shame, for

It’s a real shame, for  the book itself or the fact that it was published by the Princeton University Press. Purportedly the “twenty-five year record of ‘the finest aggregation of men that ever spent four years together at Old Nostalgia'” as penned by the class secretary, “Tubby” Rankin,

the book itself or the fact that it was published by the Princeton University Press. Purportedly the “twenty-five year record of ‘the finest aggregation of men that ever spent four years together at Old Nostalgia'” as penned by the class secretary, “Tubby” Rankin,