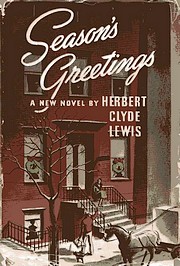

It’s fitting that the last book I feature this year is Herbert Clyde Lewis’ Season’s Greetings. His work–particularly his first novel, Gentleman Overboard, which I reviewed here back in July, has been one of the best discoveries and pleasures of this year. I only regret not getting this piece written a few days ago, since Season’s Greetings, his third novel, takes place on Christmas Eve.

The story takes us through the day in the minds of the residents of a rooming house in the Greenwich Village – Lower Fifth Avenue area of Manhattan. Mr. Kittredge–we never learn his first name–is a depressed, dyspeptic, world-weary World War One veteran who plans to commit suicide that night. Betty Carson is a young girl from Cape Cod, now working at Macy’s. Betty has discovered that she’s pregnant, by a man named Joe Henderson who left a month ago and hasn’t contacted her since. Having given up hope of seeing him again, Betty has decided to visit an abortionist after work.

The story takes us through the day in the minds of the residents of a rooming house in the Greenwich Village – Lower Fifth Avenue area of Manhattan. Mr. Kittredge–we never learn his first name–is a depressed, dyspeptic, world-weary World War One veteran who plans to commit suicide that night. Betty Carson is a young girl from Cape Cod, now working at Macy’s. Betty has discovered that she’s pregnant, by a man named Joe Henderson who left a month ago and hasn’t contacted her since. Having given up hope of seeing him again, Betty has decided to visit an abortionist after work.

Hans Metzger is a German Jew, a refugee stuck in limbo–unable to return home, unable to join his surviving sisters in South America. Minnie Cadgersmith, a widow in her seventies, suffers from a variety of ailments and has determined that she will die in her sleep that night after paying a visit to her three grandchildren. And Flora Fanjoy takes pride in having saved her pennies over the years and managed to rise from serving girl to own her own humble but upstanding rooming house.

As might be expected of any story set on Christmas Eve, each of Lewis’ main characters experiences a revelation of one sort or another in the course of the day. Soon after her tenants leave, Flora is struck on the head by a falling can of cleanser and falls down her basement stairs, landing paralyzed and unable to speak. Her only witness, her cat Flossie, soon abandons her to roam the neighborhood, and Flora gradually becomes aware that she will, in all likelihood, die before anyone comes to look for her. Lewis provides a fine passage describing how Flora learns “that there were tones and shades of blackness”:

It was nighttime, Mrs. Fanjoy realized. When first she opened her eyes the blackness had been gray, so that she had been able to discern dimly above and ahead of her the flight of stairs leading to the first floor hallway. The eyes of Flossie her cat had shone milkily opalescent in this gray blackness, she remembered. But after a while Flossie had gone away, and Mrs. Fanjoy, straining her eyes at the stairs, had watched their color and the color around them change imperceptibly to brown black, so strikingly brown black that it seeme she was lying in the center of a chocolate world. She had watched the brown black then, watched it fearfully a long time, until without warning it had vanished in the surrounding gloom, and a new color, a majestic, funereal color, had appeared to take its place. This was purple black, a blackness of such incredibly pure purple that it made each stair on the staircase stand out solemnly and distinctly from the others. And Mrs. Fanjoy had looked at the purple black, looked at it and dissected it and mentally run her fingers through its rich thickness, for a timeless time of endless minutes and hours, until, at last, she had seen it start to fade. She had watched it fade, watched it thicken and solidify and drop down into the well of darkness around her, until the last hard fleck of it was no more, and then, all of a sudden, it was black black, and Mrs. Fanjoy knew what time it was.

This quote may offer a hint of a prevailing feature of Season’s Greetings. Coming it at just over 400 pages, it’s over twice as long as Lewis’ three other books. In writing of Gentleman Overboard, I remarked that, “It’s been said that a true artist knows when to stop–and does. By this criterion alone, Herbert Clyde Lewis proves himself a true artist….”

Well, by the same criterion, Season’s Greetings proves something less than a work of art. There are plenty of places where a healthy application of blue pencil would have enabled Lewis to make his points with the kind of subtlety and grace one finds throughout Gentleman Overboard.

On the other hand, one of the great pleasures of the novel is the space it can offer the writer, the space to stretch out and explore alleys and sideways that run off the course of the main narrative–detours that can’t be afforded in a more economical form like a short story. And Lewis constantly goes wandering off into the maze of streets and lives one finds in Manhattan. He devotes a whole chapter to the thoughts of Mrs. Fanjoy’s cat, Flossie, as she leaves her owner’s side, looks around the house for food, then heads out to the tiny, barren backyard–her kingdom. Metzger befriends a bum who relates much of his life’s story, full of travel to seaports around the world and violent struggles in the early days of labor.

And he spins out many prose poems to Manhattan itself:

Very slowly the city came to life on this morning of the day before Christmas. The sun rose out of the ocean, out of Queens, out of Brooklyn, and shone listlessly through the heavy black clouds upon the slush-covered rooftops, the dirty windows, the grimy east sides of buildings, the sooty smokestacks, chimneys and air vents. Slowly the noises of the city came to life, autos shifting gears, horns honking, doors slamming shut, trains rumbling underground, machines chugging and whirling, feet tramping, babies wailing, children shouting, peddlers calling their wares. Slowly the smells of the city came to life, coffee brewing, bacon frying, garbage stewing, chemicals churling in cauldrons. And men who had a talent for putting one stone on top of another built towers into the sky so they could look down upon all this.

Needless to say, a book set in Manhattan leaves its author with no shortage of excuses to indulge in such descriptive flurries, and you’ll find them here by the dozens. Perhaps a few too many for some readers, but I was usually happy to follow along whenever Lewis strayed from his course.

Lewis had devoted much his first two books–Gentleman Overboard and Spring Offensive

–to coldly watching his protagonists die alone. And even though Season’s Greetings is a Christmas story and most of his characters reach the end of the day at least a little happier than they started, Lewis retains a bit of his trademark dispassion. As most of the other characters come together in the rooming house, Mr. Kittredge calmly walks to Washington Square, finds a secluded park bench, and blows a hole through his chest.

No one heard the loud report or saw Mr. Kittredge half rise from the bench and topple over onto the snow. A motorist driving under the arch on Fifth Avenue thought for a moment he had heard a shot, but decided it was only an auto backfiring. Around the whole windswept park, in all the apartment houses and brownstone mansions and college buildings, not a single window opened and not a single person looked out.

Lewis’ theme is, as one character puts it, “the problem of loneliness in a city of eight million people.” While Hans and Mrs. Cadgersmith find its solution in the company of others and Betty Carson is reunited with Joe Henderson instead of left alone to recover from an abortion, Lewis is too much of a realist–he was at one point a crime reporter for the New York Herald Tribune–to let Christmas miracles fix everyone’s problems. Frank Capra would undoubtedly left Mr. Kittredge out if he’d filmed Season’s Greetings.

Ironically, Liberty Films acquired the rights to another Christmas story by Lewis, “It Happened on Fifth Avenue,” intending it to be directed by Capra. Although Capra opted for “It’s a Wonderful Life” instead, a film version of Lewis’ story was released in 1947. Starring one of the best character actors of the 1940s, Victor Moore, “It Happened on Fifth Avenue” is something of a neglected film classic and earned Lewis an Oscar nomination for his original story. Lewis worked in Hollywood for about six years in the mid-forties, becoming friends with Humphrey Bogart and others, but he returned to New York City around 1948 and joined the editorial staff of Life magazine. He died of a heart attack in 1950, leaving behind a wife and two children. Some years later, somewhat inexplicably, a fourth novel, The Silver Dark was published as a paperback. All his work has been out of print for over 50 years now, and Season’s Greetings is so scarce that Amazon.com doesn’t even list it.

Here’s hoping a Christmas miracle might come to one of Herbert Clyde Lewis’ books soon.

Locate a Copy

- Find it at Amazon.com: Season’s Greetings

if they ever list a copy

- Find it at Amazon.co.uk: Season’s Greetings

- Find it at AddAll.com: Season’s Greetings

As the Russians approach, Stefan and Hannes are moved, along with other inmates, towards the West. They manage to escape when an Allied plane attacks their train, causing it to derail, but Hannes is wounded and soon dies. Stefan is interned again, this time by the Americans, as a displaced person. An American G.I., a Southerner named Moon (more symbolism), takes a liking to Stefan and eventually adopts him. After a brief spell in South Carolina, full of atmosphere straight out of Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor, Stefan returns to Europe.

As the Russians approach, Stefan and Hannes are moved, along with other inmates, towards the West. They manage to escape when an Allied plane attacks their train, causing it to derail, but Hannes is wounded and soon dies. Stefan is interned again, this time by the Americans, as a displaced person. An American G.I., a Southerner named Moon (more symbolism), takes a liking to Stefan and eventually adopts him. After a brief spell in South Carolina, full of atmosphere straight out of Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor, Stefan returns to Europe.  Significant, though? Sadly,

Significant, though? Sadly,  A lovely acknowledgement from the introduction to Geoffrey Vickers’ 1970 book,

A lovely acknowledgement from the introduction to Geoffrey Vickers’ 1970 book,