“Opening this book is like clicking on a switch: at once we hear the electric hum of talent,” Stanley Kauffmann wrote in his New Republic review of Irvin Faust’s first book of fiction, Roar Lion, Roar

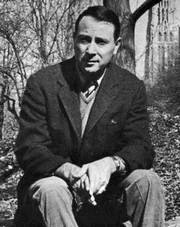

“Opening this book is like clicking on a switch: at once we hear the electric hum of talent,” Stanley Kauffmann wrote in his New Republic review of Irvin Faust’s first book of fiction, Roar Lion, Roar. And if there’s one characteristic of Faust’s work, it’s energy. For over 45 years–30 of them working nights, weekends, and vacations while holding down a regular job as a a high school guidance counselor–Faust has written some of the liveliest, noisiest, most vibrant prose published in America:

Vegas. Ocean’s Eleven. Sinatra. Judy. Thirty thousand a week. Sun. Desert. Red neon. One-armed bandits. Action. Faites vos jeux. Les jeux sont faits. Nothing Monaco. Nothing Reno. Pools. Tanfastic. Bikinis. Action. Vegas.

That’s from Faust’s first novel, The Steagle (1966), about a college professor who suffers a psychotic breakdown over the Cuban Missile crisis and goes blasting off around the country on thrill-seeking spree. Of Faust’s most commercially successful book, the 1971 novel, Willy Remembers

, Elmore Leonard wrote (in his introduction to the 1983 Arbor House reissue, reprinted on his blog):

There’s no one in American literature quite like Willy T. Kleinhans. And there is more sustained energy in the telling of what he remembers than in any novel I’ve ever read.

Willy Remembers takes off within the first two sentences, climbs, swoops, glides, does loops-all effortlessly-and doesn’t touch down again until he’s told us how things were. Really were.

It’s beautiful. More than that, Saturday Review describes it as “a great, big, beautiful hunk of Americana,” the New York Times calls it “a Book of Wonders.”

It’s so good I wouldn’t blame you if you stopped right here and turned to the first page, because all I’m going to do is tell you why I think it’s great.

A World War Two veteran who served in both Europe and the Pacific, Faust took advantage of the G. I. Bill and became a teacher in the New York Public Schools. 1954, while teaching math and English in Harlem, he decided that, “I wanted to relate to [kids] differently from the way I could in a classroom,” so he returned to school, earning a doctorate in Education at Teachers College. He returned to public schools and worked a regular Monday-to-Friday job in high schools around the New York City area for the next thirty years.

As he told Don Swaim in a 1985 interview (available on the wiredforbooks.org website), he had been jotting down story ideas for years, and in the mid-to-late 1950s, he began submitting stories to a variety of small magazines. His first book, Entering Angel’s World

As he told Don Swaim in a 1985 interview (available on the wiredforbooks.org website), he had been jotting down story ideas for years, and in the mid-to-late 1950s, he began submitting stories to a variety of small magazines. His first book, Entering Angel’s World, however, a casebook for practitioners, was based on his doctoral research and early experience as a guidance counselor. Faust once told an interviewer,

Guidance counseling hasn’t slowed me down. Actually, in many ways it has helped me to produce by getting me into the mainstream of life….

Both of these things are terribly important to me, and I love doing both. One is introverted, the other extroverted, and these are aspects of my personality. I’m very lucky to have found two things that work together for me and turn me on. I couldn’t give up either one, really.

Both Faust and his wife, Jean, were working professionals, and early in their marriage agreed that Faust would devote his precious spare time away from work to his second career as a writer. Faust’s quiet routine of working and writing has always provided a striking contrast to the vibrant, often chaotic tone of his fiction. “This pop novel pops so violently that it cannot safely be perused without welding goggles,” Time magazine’s reviewer wrote of The Steagle.

Popular culture is one of Faust’s primary energy sources. His characters revel in it, tossing in song, dance, movies, television, radio, tabloids, magazines, celebrities, and historical figures great and small with more Bam! than Emeril with a pepper shaker. A Time magazine reviewer once wrote that Faust’s protagonists “are consumed by a world of mass-produced trivia and popular mythology. They generate authentic obsessions about the inauthentic.” Again, from The Steagle:

He decided to pub-crawl and play it by ear on the outside chance of running into Selznick, who might be looking for new properties. He began drinking at eight at the hotel and worked his way along the Strip. At Lou’s Century Club he won a dance contest with a little white-haired lady who said you’re cute as a bedbug, Mr. Rooney. In the One Two Three he asked if he could sing with the combo and did “Rose Marie,” “High, Wide and Handsome,” “Don’t Give Up the Ship,” “The Piccolino,” and “Mairzy Doats.” At ten he called Selma Zorn and said baby, I’m in an all-night story conference at Metro and may have something very big. Get this: an American girl from Ohio is smuggled into Havana on a yacht owned by Harry Morgan and she does this Hayworth bit in a local bistro called Rick’s and Castro see her, and well, you get the picture, Mata Hari and Florence Nightingale, see … No, baby, I’m sorry, not tonight. No, I’m sorry. Listen, babe, listen … Selma, I’ll call you.

In the title story of Roar Lion, Roar

In the title story of Roar Lion, Roar, a Puerto Rican boy’s obsession with the New York Lions football team blurs into fantasies of becoming gridiron star himself, and much of Faust’s work is devoted to the shifting lines between reality and fiction. The very first two sentences of Willy Remembers

demonstrates how easily memory can jumble up facts and create its own version of history: “Major Bill McKinley was the greatest president I ever lived through. No telling how far he could have gone if Oswald hadn’t shot him.”

Reflecting on his writing in an interview from 1975, Faust remarked,

It seems to me that thus far my work has dealt with the displacement and disorganization of Americans in urban life; with their attempt to find adjustments in the glossy attractions of the mass media”-movies, radio, TV, advertising, etc.–and in the image-radiating seductions of our institutions–colleges, sports teams, etc.. Very often this “adjustment” is to the “normal” perception a derangement, but perfectly satisfying to my subjects.

Yet while his characters take off into flights of fantasy at the drop of a hat or the first bar of a melody, Faust has always kept his own two feet solidly on the ground. Willy Kleinhans may have confused McKinley and Kennedy’s assassins, but Faust clearly recognizes that Willy’s reveries are closer to psychotic fugues than cute, if muddled, nostalgia. Although Willy Remembers was marketed as the comic memoirs of an eccentric but lovable old man, at the core Willy’s story is full of sadness. His recollections are his escape from the grim reality of a man growing old without the comfort and company of his wife and son, who died many years before.

Sad things happen to Faust’s people, but sadness is certainly not the mood one takes away from his writing. Not everyone might be so accepting of how his characters choose to cope with their realities, but it works for them, and–with the possible exception of Faust’s 1970 novel, The File on Stanley Patton Buchta, which Jerome Charyn called “a curiously humorless book”–it usually sparkles with invention and passion.

All of Faust’s novels and short story collections are currently of a print, but all are easily available for as little as $0.01 on Amazon and elsewhere. And if you happen to wonder into a used book store that actually has inventory older than the clerk behind the counter, you shouldn’t have any trouble locating his books–they’re the ones you see glowing and buzzing on the shelves.

More on Irvin Faust

- “Scott Fitzgerald Has Left the Garden Of Allah”, one of Faust’s most recent stories, published in The Literary Review in 2008.

- A short piece on Roar Lion, Roar

–the one and only entry on Walter Cummins’ and Thomas E. Kennedy’s Great Books Forgotten or Unknown blog

- IMDB entry for “The Steagle”, the 1971 film version of Faust’s novel. Paul Sylbert, the film’s director, later published a book, Final Cut:The making and breaking of a film

, recounting how his original concept for the film–largely faithful to Faust’s story–was transformed into a pandering, pointless mess by the manipulations of Avco Pictures executives and others.

Irvin Faust’s books

- Entering Angel’s World

non-fiction (1963)

- Roar Lion, Roar

short stories (1965)

- The Steagle

novel (1966)

- The File on Stanley Patton Buchta

novel (1970)

- Willy Remembers

novel (1971)

- Foreign Devils

novel (1973)

- A Star in the Family

novel (1975)

- Newsreel

novel (1980)

- The Year of the Hot Jock

short stories (1985)

- Jim Dandy

novel (1994)

It pains me to start 2010 with two pans in a row, but few books have disappointed me as much as Vance Bourjaily’s little-known 1986 novel,

It pains me to start 2010 with two pans in a row, but few books have disappointed me as much as Vance Bourjaily’s little-known 1986 novel,  The last shows that Walton’s kept a discriminating filter on her list. Of Steig Larson’s novels, which someone nominated, she writes, “These are a stupendously successful non-genre best sellers. The opposite of obscure.” I’ve seen them on the end caps of airport bookstores in Belgium, Spain, the U.K., and the U.S. in the last two months: definitely NOT neglected.

The last shows that Walton’s kept a discriminating filter on her list. Of Steig Larson’s novels, which someone nominated, she writes, “These are a stupendously successful non-genre best sellers. The opposite of obscure.” I’ve seen them on the end caps of airport bookstores in Belgium, Spain, the U.K., and the U.S. in the last two months: definitely NOT neglected.

Although he began by calling the book “one of his [Bromfield’s] most remarkable achievements,” after devoting about four times as much text to a recap of the novel’s plot with only an occasional dig, Wilson then dismissed it as, “a small masterpiece of pointlessness and banality.”

Although he began by calling the book “one of his [Bromfield’s] most remarkable achievements,” after devoting about four times as much text to a recap of the novel’s plot with only an occasional dig, Wilson then dismissed it as, “a small masterpiece of pointlessness and banality.”