Being selected for the Pulitzer Prize is no guarantee of that anyone will remember your work–at least not more than ten years afterward. Take Stephen Bonsal. Unfinished Business

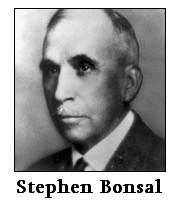

Being selected for the Pulitzer Prize is no guarantee of that anyone will remember your work–at least not more than ten years afterward. Take Stephen Bonsal. Unfinished Business, his diaries and reminiscences from the 1919 Versailles Peace Conference, where he sat between President Woodrow Wilson and Wilson’s assistant, Colonel Edward House, translating the speeches and remarks of the other attendees, won the 1945 Pulitzer Prize for History. Sixty years later, the book is as obscure as, say, Forgotten First Citizen: John Bigelow

by Margaret Clapp–the 1948 winner, by the way.

That fact alone is no great crime. There are plenty of award winners that soon lose whatever aura of excellence they might have held. And there are some, we must admit, that won only because advocates were divided over better works, opening a crack through which they slipped as dark horses of lesser merit.

When it was selected in 1945, the primary significance of Unfinished Business was probably seen in light of the impending end of World War Two and the creation of the United Nations. All parties involved in the establishment of the United Nations recognized that they had an obligation to learn from the mistakes of the past, and of the Peace Conference in particular.

The legendary version of the Peace Conference was that the idealism and altruism of the American, Wilson, was undermined by the self-interest and small-mindedness of Old Europe–of France and Italy, who insisted on reparations that gave Hitler fuel for his rise to power a dozen years later. The reality, as recalled with remarkable candor and dispassion by Bonsal, was much more mundane.

Wilson was long on ideas and brittle in character, lacking the leather-assed patience required of an effective diplomat. Small words in little clauses consumed hours of talk over fine points, and much of the time big issues pivoted on the most trivial matters:

Last night M. Larnaude [Ferdinand Larnaude, a French delegate to the Conference] again drooled along for hours in criticism or rather in misrepresentation of the Monroe Doctrine reservation, and many of his hearers feared that a filibuster was under way, but such was not the case. Suddenly pulling out his watch with an expression of alarm that was comical to behold, the learned dean muttered, “Ciel! I have only twelve minutes to catch my train, but I warn you, M. le President, that I shall resume the statement of my objections at the next Plenary Session.”

The older I get, the more I come to view politics and diplomacy as the most difficult of all arts. Bonsal’s diaries and reminiscences of the Peace Conference vividly illustrate the obstacles that lie in the path of any forward movement of mankind when it operates in a political setting. Self-interest is only the simplest and most obvious one. Personalities, temperaments, quirks, habits, and eccentricities are minefields that lurk beneath the skins of every individual at the table. Differences in working hours–Clemenceau, like Churchill, was one for naps and late hours; Wilson preferred a predictable day-time routine–toss grit in the machinery. Language, language, language: even with the finest translators (and Bonsal provided a simultaneous translation at every session Wilson attended), words and phrases are misinterpreted and misunderstood. And technology always gets in the way:

Hughes of Australia, indeed, made several outrageous attacks on the President, which, however, Wilson did not take up at one or even later because, as on the Australian secretaries explained to all present, Hughes did not understand the President’s point of view owing to the fact that, as so often before, his electrical hearing apparatus had failed to function.

Bonsal’s book opens on the eve of the Armistice and ends a little over a year later, with the Senate’s rejection of the Treaty. He worked alongside House, and later Wilson, through the preparations and initial sessions of the Conference. A veteran foreign correspondent fluent in a number of European tongues, he acted as an emissary to many of the other delegations and as a personal advisor to House and Wilson. He remained at the negotiating tables throughout most of the Conference, taking only a break of a few weeks to accompany South African General Jan Christian Smuts on a mission to Austria, Hungary, and Serbia in March and April 1919.

Bonsal’s book opens on the eve of the Armistice and ends a little over a year later, with the Senate’s rejection of the Treaty. He worked alongside House, and later Wilson, through the preparations and initial sessions of the Conference. A veteran foreign correspondent fluent in a number of European tongues, he acted as an emissary to many of the other delegations and as a personal advisor to House and Wilson. He remained at the negotiating tables throughout most of the Conference, taking only a break of a few weeks to accompany South African General Jan Christian Smuts on a mission to Austria, Hungary, and Serbia in March and April 1919.

This trip, along with a later journey to Berlin after the Conference, provide the most memorable sections of the book. Bonsal had lived in Vienna for a number of years and reported on the Balkan wars in the years leading up to the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in 1914. He notes everywhere how quickly the structures of the Hapsburg Empire crumbled away after Emperor Charles I relinquished the throne in 1918:

I visited Francis Joseph’s apartment. I saw that, as the tradition had it, there was no water laid on. I scrutinized his Gummi portable bathtub and saw that now it was full of holes. The starving mice that had formerly lived on the fat tidbits that fell from the imperial table, reduced to starving rations like all living things in the Danube capital, were gnawing on it.

Later, after the Conference, he traveled to Berlin, where he’d first met House in 1915. Bonsal found the Kaiser’s former capital in disarray, with well-meaning but overwhelmed socialists attempting to reconstruct a government while Unter den Linden was filled with wounded veterans from the war: “crouched against the cold, damp walls as though ashamed for the stranger to see their distorted leg and arm stumps, their dead eyes, or their faces scarred almost beyond recognition.”

Coming back from Berlin, his train is joined at Verdun by hundreds of veterans and their families, returning from some anniversary celebration of the great battle. Just as in Berlin, he finds the war’s destruction surrounding him: “This train, crowded with those who survived, was a more horrible sight than any of the many ghastly battlefields I have witnessed in so many lands. All about me were’ groups of grand blessés, many with grotesquely distorted faces…. As I traveled with this cavalcade of misery and of suffering, I realized more fully than ever before the terrible price our generation has paid for his victory.”

Arriving in Paris late at night, he watched the train’s passengers depart the station and head back to their homes:

The train hobbled into Paris about midnight. After standing in the crowded corridor with my heavy pack for eight hours, I found I could hardly walk. I leaned against an iron pillar and watched and watched and waited. Slowly the silent mob of the lame, the halt and the blind, the crape-draped widows, and the pale-faced, sad-eyed orphans of some of the four hundred thousand gallant soldiers who died defending the great fortress against the onrush of the invading Germans, dissolved. For me the pomp and pageantry of war had vanished for a long time, perhaps forever, and what remained was misery and tears, loneliness and squalor. It was hours before the last of the war widows, carrying children who would never see their fathers, disappeared into the darkness of the city where victory perched. But I shall see them always?always.

Neglected though it may be, Unfinished Business is an exceptional book worth rediscovering by anyone interested in history and politics. There are not many writers who can cover the posturing and manoeuvring of the greatest men of the time and, a few pages later, describe the sorrows and woes of the lowest in society–and in neither case losing his sense of perspective. As Time magazine’s reviewer wrote, “”no one else has presented the plight of the plain people of Europe, in relation to the strained secrecy of the Conference, and few have written of their agony as does Colonel Bonsal in terms so hardheaded and so poignant.” I hope one of these days to catch up with his 1937 memoir of his years as a foreign correspondent, Heyday In A Vanished World

.

Find a Copy

- Find it at Amazon.com: Unfinished Business

- Find it at Amazon.co.uk: Unfinished Business

- Find it at AddAll.com: Unfinished Business

I think it was in the long-gone Filippi’s Books in Seattle that I came across the

I think it was in the long-gone Filippi’s Books in Seattle that I came across the  Simon and Schuster published at least seven other Fireside books on sports and games, including:

Simon and Schuster published at least seven other Fireside books on sports and games, including: These were not at all like my mom’s cookbooks. These were cookbooks written for men by a guy without a shred of doubt about his studliness. What cookbook written by a woman would put “Meat” at the front, on the very first page? And lead off with, “How to Make Real Corned Venison, Antelope, Moose, Bear and Beef”? The last is just a concession to the little ladies, I’m sure. The author,

These were not at all like my mom’s cookbooks. These were cookbooks written for men by a guy without a shred of doubt about his studliness. What cookbook written by a woman would put “Meat” at the front, on the very first page? And lead off with, “How to Make Real Corned Venison, Antelope, Moose, Bear and Beef”? The last is just a concession to the little ladies, I’m sure. The author,