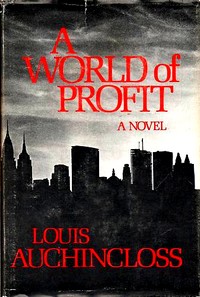

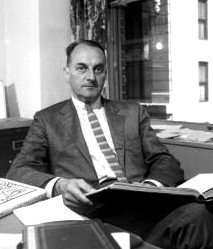

I must admit that I did not note Louis Auchincloss’ passing at the age of ninety-two in late January. For at least the last ten years, Auchincloss, whose career as a writer spanned over sixty years and produced over sixty books, seemed either to be someone I’d thought had already died or just assumed would live forever. For more than my entire life, he’d been publishing, publishing, publishing.

His productivity and energy seem to have come from another generation, from the Victorian and industrial age. He worked for over forty years as a lawyer in the heart of Wall Street and the East Coast establishment. He sat on the boards of museums and academies, and he knew everyone. He was president of the Century Association, probably the most exclusive cultural association in America, and a member of New York’s best clubs. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Gore Vidal were related to him through second- and third-marriages. His wife was related to the Sloanes and Vanderbilts. He attended Groton alongside FDR’s son John and shared a room with William Bundy. He lunched with Brooke Astor at the Knickerbocker Club. In 2003, he was feted, along with Princess Yasmin Aga Khan and Blaine Trump, as one of seven “New Yorkers who make a difference.”

His father was also a New York lawyer and confidant of the wealthy and powerful. Auchincloss would always demur about his family’s place in society: “We were wealthy by the standards of the globe, not by the community.” But they managed summers at Bar Harbor, Maine, where Prescott Bush set up a family summer house. Not that the Auchinclosses and Bushes mingled: he once remarked to a Financial Times interviewer, “I just think the Bushes are a big family of shits. They might have existed anywhere.”

There is so much in that short quote. It’s not President George W. Bush, who presented Auchincloss with the National Arts Medal in 2005, that he condemned–it was the whole family, and for, one suspects, crimes against manners and culture rather than society. Then there is the use of the word “shits.” Most Americans would be more inclined to say something like, “full of shit,” but to call someone a “shit” is very much an upper crust idiom.

The world of New York, of wealth, elite society, and the law was the world Louis Auchincloss lived in and wrote about. For the first two, he was often and will forevermore be written of as the successor to Edith Wharton (and indeed, Edith Wharton: A Woman in her Time was the first of a number of biographies he published). He dismissed suggestions that he took a narrow view in his choice of subjects. He told an Atlantic interviewer in 1997:

was the first of a number of biographies he published). He dismissed suggestions that he took a narrow view in his choice of subjects. He told an Atlantic interviewer in 1997:

If you look through the literature of the ages you will find that ninety-five percent of it deals with the so-called “upper class,” from The Iliad and The Odyssey through to Shakespeare with his kings and queens. If you go through the nineteenth-century novelists you will find much the same thing. Take a novel like War and Peace — the characters are taken not only from the upper class but from the very small upper-upper class that ruled Russia at the time. And yet Tolstoy is given credit for having written a “world” novel. It’s as if Norman Mailer had written The Naked and the Dead and made every Marine or Army man on that island a graduate of a New England private school. That would be quite a shocker to people, yet that is War and Peace.

I’m not sure he convinced many people with that argument. In her 2007 biography, Louis Auchincloss: A Writer’s Life , Carol Gelderman quotes Lady Bird Johnson–a sharper judge of character than she’s usually given credit for–on meeting him: “… polished, very Eastern. I couldn’t imagine him living or writing about life west of the Mississippi River.” “She could have said Hudson River and been just as accurate,” Gelderman adds. The Christian Science Monitor’s book critic, Heller McAlpin, had a lovely, if fainting damning, comparison for his work:

, Carol Gelderman quotes Lady Bird Johnson–a sharper judge of character than she’s usually given credit for–on meeting him: “… polished, very Eastern. I couldn’t imagine him living or writing about life west of the Mississippi River.” “She could have said Hudson River and been just as accurate,” Gelderman adds. The Christian Science Monitor’s book critic, Heller McAlpin, had a lovely, if fainting damning, comparison for his work:

There’s something oddly comforting about reading this patrician novelist of manners, successor to Edith Wharton. You know, to a certain degree, what you’ll be served — rather like eating at an exclusive social club. The food is rarely exciting, but it’s never alarming, either, and it’s impeccably presented. Manners are genteel, language is as proper and crisp as white linen napkins, and everyone is educated and well-heeled. It all feels like a throwback to a more gracious time.

Heller’s description recalls this passage from Dinitia Smith’s 1986 profile of Auchincloss for New York Magazine:

The Downtown Association, for instance, is Louis Auchincloss territory, the world of old money, of deals made behind closed doors. Like a number of the great clubs, the DTA, as it’s called, doesn’t even have a sign over the door. Your’re just supposed to know it’s there. The decor is a bit understated. The food is uninspired–one choice is tuna fish in a shell of tomato with dollops of mayonnaise for decoration, and desserts include those WASP staples, rice pudding with raisins and cabinet pudding.

But Auchincloss was no idle spender of old money. He was a working lawyer, which got him into rooms that would never have been open to Wharton as a mere woman and writer. He started out with the prestigious firm of Sullivan and Cromwell before World War Two, and later ran the trust and estates department of Hawkins, Delafield, and Wood. Vidal once wrote of him, “He is the only one who tells us how our rulers behave in their banks and their boardrooms, their law offices and their clubs … things that we don’t often meet in fiction.”

The law was always his second choice, though. While attending Yale as an undergraduate, he wrote a long novel modeled on Madame Bovary. When it was rejected by Scribners, he decided to renounce literature and become a lawyer. While studying at the University of Virginia Law School, though, his passion for writing returned: “I stumbled into Cardozo’s opinions, I became fascinated by his style and realized that the two occupations, law and writing, are more or less synchronized. I began the two careers I would follow from then on, law and writing. That summer I started a novel; the second summer I finished it.” Even as a lawyer, his talent for writing came out. Auchincloss loved to relate a comment made by the young Mario Cuomo upon reading a brief of his while clerking for the New York Court of Appeals: “The guy who wrote this ought to be a novelist!”

Graduating in 1941, Auchincloss was barely able to get started in his career in the law before being pulled into the Navy, where he served in Panama and captained an LST on D-Day. He started a third novel, The Indifferent Children , which he originally published in 1947 under the pseudonym of Andrew Lee at his mother’s insistence. She thought it “trivial and vulgar.”

, which he originally published in 1947 under the pseudonym of Andrew Lee at his mother’s insistence. She thought it “trivial and vulgar.”

On nights and weekends while working at Sullivan & Cromwell, he started writing short stories, a few of which he managed to sell to The Atlantic Magazine and Town and Country. In 1950, he sold his first collection to Houghton Mifflin, which remained his publisher until his death–a record itself rare, if not unique, in the world of publishing. The Injustice Collectors (first published in paperback as The Unholy Three and Other Stories

(first published in paperback as The Unholy Three and Other Stories ) was the first of many short story collections he would publish during his life–the last being The Friend of Women and Other Stories

) was the first of many short story collections he would publish during his life–the last being The Friend of Women and Other Stories (2007).

(2007).

He was never a typical writer. Though he was friends with Ralph Ellison, travelled as a cultural ambassador with Arthur Miller and Allen Ginsburg, and served as president of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, his work as a lawyer kept his routine within strict limits. He once told an interviewer,

When I married Adele, she said, Oh, we’re going to see all these wonderful writers. One night Calder Willingham called just as we were about to go to bed. He asked if we’d come out and drink with him. I said, Well, I don’t think Adele wants to do that. Then why don’t you come? His idea was we’d sit up all night. I said, No, I don’t do that. I had to get up in the morning.

That routine–and the support of an effective agent and a loyal publisher–paid off. Auchincloss published 31 novels, 17 short story collections, 17 works of nonfiction, at least a half-dozen coffee table books such as J.P. Morgan: The Financier as Collector , and contributed introductions and afterwords to dozens of other books, including numerous reissues of works by Edith Wharton.

, and contributed introductions and afterwords to dozens of other books, including numerous reissues of works by Edith Wharton.

How did he manage such a volume of work, particularly during forty years of Monday-to-Friday work as a lawyer?

One secret was a knack for writing in little snatches of time. He told George Plimpton for his Paris Review interview in 1994:

I’ve always had to use bits of time. For example, I would have little notebooks with me in court, and if I was waiting for something I might write a few paragraphs at a time. By mastering the ability to use five minutes here, fifteen minutes there, I picked up a great deal of time that most people allow to drift away.

I remember seeing an opera rehearsal once in which the conductor put down the baton, the singers stopped, and then he picked it up to go again. If I was singing I’d have to go back to the beginning. But no! They picked up right on the particular note they left off on. That’s what I’ve learned to do with my writing.

I can pick up in the middle of a sentence and then go on. I wrote at night; sometimes I wrote at the office and then practiced law at home. My wife and I never went away on weekends. I wouldn’t recommend that anyone else try this method, but it worked for me.

Not worrying over what got scribbled into his notebooks helped, too. It was rare that he spent much time on rewrites. “… [O]rdinarily I find that when I have to rewrite, there’s something basically wrong. My best stuff usually comes out quite straight almost the first time,” he told Plimpton.

Writing the same book over and over–or, at least, using the same formula over and over–also kept his rate of production high. The use of multiple narrators and mixing first and third-person voices, which was cited by many as the distinguishing feature of his most critically successful book, The Rector of Justin , was, in fact, his standard approach to a novel. As Jonathan Yardley summarized it in his “Second Reading” of the book in 2008:

, was, in fact, his standard approach to a novel. As Jonathan Yardley summarized it in his “Second Reading” of the book in 2008:

The novel begins in September 1939 and ends in April 1947. It is told principally through the diary of Brian Aspinwall, who comes to Justin Martyr at the age of 27 as an instructor in English and soon believes “that I may have a call to keep a record of the life and personality of Francis Prescott,” who “is probably the greatest name in New England secondary education.” Five other narrators contribute to the portrait: David Grisham, chairman of the trustees, chief architect of the school’s wealth; his son, Jules, expelled by Prescott for an act of defiance; Horace Havistock, Prescott’s oldest friend, “a remnant of the mauve decade”; Cordelia, Prescott’s rebellious daughter; and Charley Strong, one of Prescott’s “golden boys, Justin ’11, senior prefect and football captain, a kind of American Rupert Brooke,” who fled to Paris after World War I and underwent a crisis of identity and faith.

One can find the same technique in such works as The House of the Prophet , based on the life of Walter Lippmann, The Embezzler

, based on the life of Walter Lippmann, The Embezzler , inspired by but not entirely faithful to the story of Richard Whitney, one-time president of the New York Stock Exchange, and Honorable Men

, inspired by but not entirely faithful to the story of Richard Whitney, one-time president of the New York Stock Exchange, and Honorable Men (loosely taken on the careers of his Groton classmates Bill and McGeorge Bundy).

(loosely taken on the careers of his Groton classmates Bill and McGeorge Bundy).

In some cases, the line between his short story collections and his novels is hard to determine, particularly given his penchant for publishing stories linked by a particular theme or setting. The stories in Powers of Attorney , for example, revolve around partners and attorneys in the fictional firm of Tower, Tilney & Webb. The novel East Side Story

, for example, revolve around partners and attorneys in the fictional firm of Tower, Tilney & Webb. The novel East Side Story is a series of eleven portraits of members of the Carnochan family from colonial to modern days. Fellow Passengers: A Novel in Portraits

is a series of eleven portraits of members of the Carnochan family from colonial to modern days. Fellow Passengers: A Novel in Portraits made the construct explicit in its subtitle, as did The Partners

made the construct explicit in its subtitle, as did The Partners , which cautions the reader that it is, “Not a novel in the conventional sense,” but rather a series of sketches of another fictional law firm, Shepard, Putney & Cox. But even novels lacking these disclaimers, such as The Education of Oscar Fairfax

, which cautions the reader that it is, “Not a novel in the conventional sense,” but rather a series of sketches of another fictional law firm, Shepard, Putney & Cox. But even novels lacking these disclaimers, such as The Education of Oscar Fairfax , The House of Five Talents

, The House of Five Talents , and False Gods

, and False Gods were essentially collections of character sketches rather than strong linear narratives.

were essentially collections of character sketches rather than strong linear narratives.

The same can be said of many of his non-fiction works: The Vanderbilt Era: Profiles of a Gilded Age , Persons of Consequence: Queen Victoria and Her Circle

, Persons of Consequence: Queen Victoria and Her Circle , The Man Behind the Book: Literary Profiles

, The Man Behind the Book: Literary Profiles , and Writers and Personality

, and Writers and Personality are all collections of biographical sketches, most of them originally published in magazines.

are all collections of biographical sketches, most of them originally published in magazines.

And, in truth, the magazine piece–whether fiction or non-fiction–was Auchincloss’ forte. Open one of his books at random and you’re likely to find, on the copyright page, a note to the effect that, “Some of the [stories/pieces] in this book have appeared in …” followed by a list that ranges from the Saturday Evening Post, American Heritage, and the New Yorker, Esquire, Harper’s, and the Atlantic to McCall’s, Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping, and Redbook to the Virginia Law Review and the Yale Literary Magazine.

This is not to dismiss his accomplishments, however. To publish hundreds (thousands?) of pieces in such a variety of mainstream magazines over the course of six decades required a remarkable ability to consistently produce an interesting, well-written, and fairly succinct story. And if the character sketch was what Auchincloss was best at, then he truly had few peers. Back in 2002, Russell Baker reviewed Edmund Morris’ 772-page second volume of his biography of Theodore Roosevelt alongside Auchincloss’ 155-page work in Arthur Schlesinger’s “The American Presidents” series, and it’s easy to see who emerged the winner in Baker’s view: “Louis Auchincloss’s concise Theodore Roosevelt , which compresses the full life, cradle to grave, into an elegant 136 pages, is a dandy handbook for the reader seeking guidance through Morris’s great forest.”

, which compresses the full life, cradle to grave, into an elegant 136 pages, is a dandy handbook for the reader seeking guidance through Morris’s great forest.”

Throughout Auchincloss’ works, the example of the Duc du Saint-Simon, the legendary memoirist of the court of Louis XIV, keeps popping up. Indeed, he once wrote a novel–The Cat and the King –fantasizing that the duke kept on writing after his memoirs were published. “The Single Reader,” a story from Powers of Attorney

–fantasizing that the duke kept on writing after his memoirs were published. “The Single Reader,” a story from Powers of Attorney , was about a lawyer who was secretly recording the life of Manhattan society in a diary inspired by Saint-Simon’s:

, was about a lawyer who was secretly recording the life of Manhattan society in a diary inspired by Saint-Simon’s:

Inevitably, he came to think of his people as they would one day appear in his diary. If a judge was rude to him while he was arguing a case, if a government official was quixotic or arbitrary, Madison would reflect with an inner smile that they were marring their portraits for posterity. Yet he took great pains to avoid the prejudices which he suspected even in his idol, Saint-Simon. Most of the people whom he knew, like many of Saint-Simon’s, would survive to posterity only in his own unrebuttable pages. If he succumbed to the temptation of “touching them up,” of making them wittier or nastier or bigger or smaller than they were, nobody in a hundred years would be any the wiser. But his work would have become fiction, and he had no intention of being a mere novelist.

So, in making my closing argument in the case of Louis Auchincloss, let me quote from just one of the thousands of character sketches to be found in his oeuvre, a body of work certainly not packaged like Saint-Simon’s but certainly rivalling it in the wealth of observations about men and women in work and society. And it’s fitting that it be one of a lawyer–in this case, one Waldron P. Webb, partner of Tower, Tilney and Webb, the firm depicted in Powers of Attorney , in the story, “The Ambassador from Wall Street”:

, in the story, “The Ambassador from Wall Street”:

Webb himself was a trying visitor, almost impossible to entertain. He was one of those lawyers who were frankly bored by everything but the practice of law. He was a big, stout choleric man, with a loud gravelly voice that was made for the cross-examination of hostile witnesses and not for gossip under the umbrellas. He indulged in no known sports, would not even swim, and expressed his contempt for the country in the uncompromising black of his baggy linen suit and the damp cigar that was always clenched between his yellow molars. He wandered about the house, pulling books out of the bookcases which he would then abandon with a snort, and asking for whiskey at unlikely hours. Mrs. Webb, the kind of forlorn creature that loud, oratorical men are apt to marry, contemplated him with nervous eyes, hoping, perhaps, that he would wait until they were alone before abusing her.

Auchincloss’ industry has not yet stopped producing, despite his death. In December, 2010, Houghton Mifflin will publish A Voice from Old New York: A Memoir of My Youth –a successor to his 1974 memoir, A Writer’s Capital

–a successor to his 1974 memoir, A Writer’s Capital .

.

Gene Lees, one of the finest jazz writers ever, passed away a few days ago. Without a doubt, his best work was the series of jazz portraits and memoirs he published in his long-running journal, Jazzletter, which were collected in such books as Cats of Any Color and Meet Me at Jim & Andy’s. He was also a fine lyricist, best known perhaps for his English version of Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Corcovado,” which Lees transformed into the lovely “Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars.”

Gene Lees, one of the finest jazz writers ever, passed away a few days ago. Without a doubt, his best work was the series of jazz portraits and memoirs he published in his long-running journal, Jazzletter, which were collected in such books as Cats of Any Color and Meet Me at Jim & Andy’s. He was also a fine lyricist, best known perhaps for his English version of Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Corcovado,” which Lees transformed into the lovely “Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars.”