One of my earliest posts on this site was devoted to Vasily Grossman’s epic of the Russian experience in World War Two, Life and Fate. At the time, it was out of print in English translation and had been for over a decade.

Since then, Life and Fate has been reissued as a New York Review Books Classic and Grossman’s work has found a substantial audience. His wartime reporting has been collected as A Writer at War: A Soviet Journalist with the Red Army, 1941-1945

, and about a year ago, his last work, An Armenian Sketchbook

, previously unavailable in English, was translated by Robert Chandler and released as another NYRB Classic.

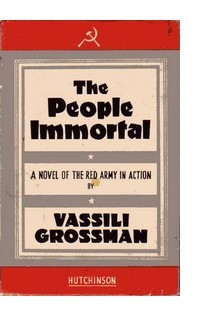

A year or so before I started this site, I came across a copy of Grossman’s first book published in English: The People Immortal in a Charing Cross bookstore that’s since become a pseudo-French bakery. It was in the bargain shelf, priced at one pound.

Out of curiosity last week, I decided to see what it was going for, given Grossman’s recent fame, and found a grand total of one copy for sale, priced at over 100 pounds. Which motivated me to dig it out and give it a read. Now, if by the end of this post you decide you can’t live without a copy, my recommendation is to opt for the U.S. edition, which was published by Julian Messner in 1945 under the title of No Beautiful Nights (there are three copies currently available).

In the English translation, credited to Elizabeth Donnelly in the U.S. edition, The People Immortal appears to be an abridgement of the Russian original, with a shorter text and four fewer chapters. How much has been lost, I cannot tell for certain, but given that Grossman shifts between characters and scenes, much as he did on a much grander scale in Life and Fate, it would have been easy to drop a chapter here and there without affecting the principal narrative.

The People Immortal takes place over the space of about ten days in August 1941, and follows a number of Russian soldiers and civilians as they retreat in the face of the German invasion. When first published in 1942, the book was something of a best-seller and was widely acclaimed. Grossman was nominated for the Stalin Prize for literature that year, but Stalin vetoed the selection and gave the prize to Ilya Ehrenburg instead. At the time, it must have been quite effective as propaganda, as Grossman displays throughout the book a profound confidence in the superiority of the Russian character, which he sees as more significant in the long run than the Germans’ military advantage.

As a work of fiction viewed from a distance of seven decades, it’s an uncomfortable mix of fine descriptive writing and simple Russian boosterism. I say boosterism simply because Grossman’s book lacks the fire and brimstone of the most strident Soviet propaganda. The Germans are referred to as “Germans,” for example, when a hardcore Soviet writer would call them “Hitlerites.” That’s not to say that he doesn’t engage in an occasional bout of character assassination: “German creative thought has been rendered sterile in all fields–the Fascists are powerless to create, to write books, music, verse,” remarks his chief protagonist, Commissar Bogarev, at one point.

Grossman’s approach to propaganda is less to denigrate the Germans than to highlight the most positive aspects of the Russian character. Thus, we get the stoic and indomitable leader (Bogarev), the salt-of-earth Russian mother, the happy-go-lucky soldier who breaks into song to rally his comrades when the going gets rough. Indeed, much of this will be familiar to anyone who’s ever seen the Hollywood equivalent from World War Two:

Casualties among the men were heavy. Red Army man Ryabokon fought to his last round of ammunition; Political Instructor Yeretic, after downing scores of the enemy, blew himself up just before he died; Red Army man Glushkov, surrounded by the Germans, went on firing till his last breath; machine-gunners Glagoyev and Kardakhin, faint with loss of blood, fought as long as their weakening fingers could press the trigger, as long as their dimming eyes could see the target through the sultry haze of battle.

On the other hand, The People Immortal is redeemed somewhat by Grossman’s frequent use of nature as a means to set the war in perspective. Even greater than the strength of the Russian people is the resilience of the Russian land. As one soldier lies in a field, waiting for the command to rise and attach a German outpost, he notices the life going on around him:

Running across the dry ground is a crack like a fine streak of lightning. The column of ants winds along a bridge in strict order, one after the other, while those of the other side of the crack patiently wait their turn. A lady-bird–a plump little old woman in a bright red dress–is hurrying along, looking for the crossing. A gust of wind, and the grasses sway and bow, each in its own way, some humbly and quickly prostrating themselves to earth, others stubbornly, angrily, quivering, their ears spread out–food for sparrows.

It may also be that The People Immortal is redeemed by its brevity. Grossman puts his cast into a quandary–being trapped behind German lines, rescues them with a bout of ingenuity and heroism, and brings the story to a quick end. Another hundred pages and it might have become, as someone once described his next novel, For a Just Cause, which has not been translated into English yet, “a Socialist Realist dog.”

In the end, though, like that book, The People Immortal is of interest today only as an early and largely unsuccessful prototype of Life and Fate. Only a Grossman completist should consider hunting down a copy.

This is interesting post, and immortality becomes real after being discovered by Allen Omton and Serge Dobrow

I own a copy of Stalingrad, the German translation of the next novel, titled but not translated into English For a Just Cause. Several years ago I bought, read, and sold the People Immortal.

Very helpful information. Thanks for passing this along.

The People Immortal is also included in full in a larger volume of Grossman’s writings titled The Years of War (1941-1945), published by the Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, in 1946. It forms the first 151 pages of a 451 page volume which brings together fictional and non-fictional writing by Grossman on the Great Patriotic War, divided into years. The translations in the volume are credited to Elizabeth Donnelly and Rose Prokofiev. It’s a rather attractively-produced hardback which I picked up for the princely sum of 30 pence on the Sale shelf in a bookshop in Tbilisi, Georgia. It’s on UK Amazon for £60 and US Amazon for $50, but I’m sure I’ve seen it for less elsewhere.

For a Just Cause is interesting- or would be, if we could get hold of it- because Grossman wrote several versions, according to what he thought would be publishable at different times and because Life and Fate is a sequel, or was originally planned to be a sequel, sharing several characters.