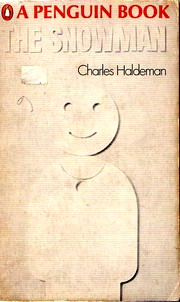

For the first fifty-or-so pages of The Snowman, I thought I’d really found a long lost–heck, a never-discovered–gem. I picked up the Penguin paperback edition at a bookstore in Seattle, attracted by several promising clues. The Penguin edition came out four years after the initial hardback release; despite the fact that the novel was written by an American and is set in America, it appeared to have been published only in the U. K.. The blurb on the back read cryptic enough to suggest something worth investigating:

The Snowman

is often infuriating, always compelling, a blinding collage of cross-threads, dead-ends, endless tunnels, red herrings and bang-on target salvos of smouldering reality.

And at first, the work itself seemed a wonderfully bizarre treat. The first chapter ones with an entry from The Motorist’s Guide to Upstate New York, 1939: “Joseph’s Landing (232 alt. 729 pop.) 1.6 miles from State 3, is a peaceful lakeside village of wided, shaded streets and roomy old dwellings first settled in 1802.”

Over the next few chapters, Charles Haldeman introduces us to Joseph’s Landing and some of its inhabitants, past and present. It is, to say the least, an unusual place. There is something odd about everyone in the place. Here, for example, is a bit of town history:

Donatien’s death left Melba and Claude Hagen swamped in the peaked and parapeted four-story sandstone monstrosity at the acute intersection of Joan of Arc and Pierre de l’Hôpital Streets. Even when the ground floor had been overflowing with patients and Melba was holding a D.A.R. convention upstairs, the house had still seemed empty, it was so huge. Its original designer and builder, General Gilbert Raye, had obviously suffered from daedalomania. But that wasn’t all he’d suffered from: in 1819, not five years after the last stone was set in his labyrinth, he and a down-eastern prelate were arrested for conducting experiments of an unspeakable nature and sentenced to be hung by the neck until dead and then burnt. Donatien’s great-grandfather Count Joseph de Villiers, a pseudonymous self-made noble who had absconded with the Spanish crown jewels afer the Battle of Waterloo and come to America with grandiose plans for establishing a new French Empire in the North, recognized in the condemned general a kindred spirit and paid him several visits in his cell. On the eve of his execution the wretched man gratefully bequeathed his eyesore to his friend.

This combination of the baroquely bizarre (“daedelomania”; “experiments of an unspeakable nature”) and the down-to-earth (“eyesore”) reminded me in a powerful way of one of the first books I featured on this site, John Howard Spyker’s Little Lives. I could imagine Joseph’s Landing sitting in the heart of Spyker’s Washington County. I even began to wonder if Charles Haldeman was yet another Richard Elman’s pseudonyms.

Unfortunately, the promise is unfulfilled. We move from these lovely odd vignettes into a series of chapters focusing on one and then another resident, most of them leading nowhere and weaving threads never again picked up in the narrative. Penguin’s blurb above is not intriguing praise. It’s a literal description. Haldeman seems to have been unable to decide just what he was writing. In the end, he settles upon a story of misfits and outcasts finding a kind of peace among themselves–the material of a Flannery O’Connor story, but not the end product.

His first novel, The Sun’s Attendant, published just a year or so before The Snowman, apparently suffered from similar problems. One reviewer praised its “Joycean” language but found it an artistic failure. Haldeman told the story of a child survivor of Auschwitz through a variety of textual artefacts but in the eyes of most critics at the time, didn’t manage to bring these pieces together into an effective whole–and he certainly didn’t manage to get past this stage with The Snowman.

Thank you for the comments on Charles’s books by Jean-Marie Clarke and Sylvia Dellinger. “The Sun’s Attendant” (“Der Sonnenwächter”) was published in German translation (I now own the copyright) in 2015 by Metrolit and by Buechergilde Gutenberg. It contains an excellent “Nachwort” by Martin Meyer and has received a number of favorable reviews in the German press.

Ms. Dellinger: Charles attended Erskine only one year, 1948-49, so he would not have overlapped with you. I, his brother, was director of public relations at Erskine from 1961-95. My wife is professor-emerita of biology at Erskine, where she has taught since 1967. The Erskine Library has a copy of “The Sun’s Attendant” and you should be able to find copies of both it and “The Snowman” online if your library does not have them.

Anthony Quinn: I would be most interested in your recollections of Charles. My email is dhaldemn@erskine.edu. Are you related to the late actor Anthony Quinn, whom Charles met on Crete while he was making “Zorba the Greek”?

Richard H. Haldeman, brother of Charles Haldeman

I randomly found this website as I graduated from Erskine in 1957. I don’t remember him and I had never heard of his books. Now I am eager to see if our library has his books so that I may judge for myself.

My life was very dull. Married classmate, four children, taught school, retired, living near my children in Charleston, SC. I deserve another chance.

Sylvia Dellinger

I have already left a comment on the review of “The Sun’s Attendant,” for which I have the highest regard, in spite of its quirks and ambition. It is the only novel I have read three times and look forward to reading again. Just as vivid are my memories of reading “The Snowman” (twice) which is less of a haphazard treasure trove and more of a finely-crafted gem. There is something haunting about Haldeman’s characters, they are anything but one-dimensional, and while his style often comes across as self-conscious, that seems to be the price to pay for his particular intensity. I cannot say the same for “The Tea-Garden Gang,” which was clever and entertaining, but not as humanly engaging as his first two novels.

Again, I would be happy to contact those who own the copyright to “The Sun’s Attendant” for a German translation.

On holiday in Platanias ,Crete in 1979 , I met Charles……I have amazing memories of him … I can be contacted on anthonyquinn141@btinternet.com

Have just come across my mother’s first edition of The Snowman – hardback with dust jacket still intact. I remember her receiving this book as a present when it first came out and now I’m looking forward to reading it for myself.

Thanks for the source of information about Charles’s books. We were assured by the person who took the house in Hania from him that his books were contributed to the library in Hania (he again assured my brother Neil of this today) . That seems highly unlikely. All of the books mentioned were probably his, as Hadjidakis and Gatsos were friends of his. This sheds more light on the entire case concerning his home on Crete – a tale of lies and deceit that would make an excellent novel itself.

Thank you so much for sharing this information about your brother’s life and work. Despite my critical assessment of the novel, I consider it an obligation to commemorate the work of writers who failed to get picked up by the mainstream of literary history and criticism.

The reference to the books along the roadside came from this 2001 article from Gay & Lesbian Review about Charles Henri Ford. About 3-4 pages in, the writer, James Dowell, states:

I am the next youngest of four younger brothers of the author Charles Haldeman. This blog has caused a great deal of concern for us and for others of Charles’ friends who have contacted us, especially the note that his books were “scattered along the side of a road in Crete.” At the time of his death in January 1983 Charles was engaged in a legal case to keep the Venetian villa he had restored in Hania. This case was eventually lost by our family. Charles had lived in Hania from 1964-74 and we had wondered what became of his books and manuscripts there. He lived in Greece, teaching at the American School in Athens, writing his first novel on Mikenos, and living in Athens and Hania, from 1958-83. His first novel, The Sun’s Attendant, was praised by both the London Times Literary Supplement as arousing “the kind of puzzled excitement that can sometimes mark the entrance of an outstanding writer,” and also drew praise from The Saturday Review and publication in 14 languages. It was based largely on his experiences in Germany during the 1950s, where he studied two years at his (blood) father’s alma mater, Heidelberg University, and met his German relatives (he and I were sons of a German immigrant Charles Heuss who died when Charles was three and I a baby. We were adopted by our mother’s second husband, Willard Haldeman, father of our younger brothers). The Snowman also received favorable reviews and came out in paperback. Unfortunately, The Sun’s Attendant came out with bad timing, at the same time as the Kennedy Assassination in 1963 when the world moved into the turbulent 60s and away from World War II novels. In 1967 20th Century Fox accepted a screenplay by Charles to be filmed in Greece, only to cancel this after the Colonels took over – another case of bad timing. The next year – 1968! – Charles brought the script for a musical play to New York. Though he was unable to find a producer there, the play was later performed in Athens. Charles final published novel, Teagarden’s Gang – definitely not a “children’s book – was published in 1971. A satirical, bitter book on American life, it was unable to find an American publisher because a main character was too closely identified with J. Edgar Hoover, still powerful and living. At the time of his death he was writing a three-part novel based on his life in Greece and attempting, with friend and director Christopher Miles, to sell a movie script, The Cretan Runner, based on a book about the Cretan resistance to the Nazis during World War II. Charles also wrote the script for a number of British and Canadian documentaries, including an award winning film on Greek icons. He edited International History Magazine for four years in the 1970s. As a teenager when we were living in Sarasota, FL (one of a dozen or so places where we grew up) he studied at Ringling School of Art and was also a fine artist. Charles was much beloved in Greece and had many friends in Athens and in the international literary community. He was a novelist, poet, artist, screen writer, and documentary writer and perhaps the novel was not the best form to express the complexities of his mind. He was a brilliant conversationalist, usually the center of any conversation. I am glad that his books are still being read – even rarely – and hope this brings a netter understanding of him.

Thanks for the additional info, Robert. I also found an article whose writer mentions coming across hundreds of books scattered along the side of a road in Crete. When he stopped to take a look at them, he discovered that a number of them were marked with Charles Haldeman’s name. This was in 1983 or 1984, probably after Haldeman’s death.

Some additional notes, gleaned online: Haldeman was born in South Carolina and died and was buried in Athens. He was a protege of Lawrence Durrell and figures in Gordon Bowker’s biography of the latter. The poetry book (or chapbook – it’s just 16 pp) is still available from its publisher, Five Seasons Press. According to FSP’s site it has a checklist of novels, “published and unpublished.”

Abebooks shows The Snowman, like The Sun’s Attendant, was published in the US – by Simon & Schuster, no paperback reprint here for either. A vendor at Abebooks states Haldeman was born in 1931 and died in 1983. He published one more volume in his lifetime, a children’s book, “Teagarden’s Gang,” with Jonathan Cape in the UK in 1971. A year after his death a small press published a collection of poetry, “Without Graves – No Resurrections.” This had a preface by the British writer Peter Levi.