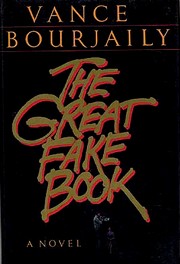

It pains me to start 2010 with two pans in a row, but few books have disappointed me as much as Vance Bourjaily’s little-known 1986 novel, The Great Fake Book. As an amateur jazz player, I was attracted by the title, a reference to fake books, the cheat sheets many working musicians use to memorize popular tunes. [Barry Kernfeld wrote a short history of them, The Story of Fake Books: Bootlegging Songs to Musicians, a few years ago.]

It pains me to start 2010 with two pans in a row, but few books have disappointed me as much as Vance Bourjaily’s little-known 1986 novel, The Great Fake Book. As an amateur jazz player, I was attracted by the title, a reference to fake books, the cheat sheets many working musicians use to memorize popular tunes. [Barry Kernfeld wrote a short history of them, The Story of Fake Books: Bootlegging Songs to Musicians, a few years ago.]

Bourjaily’s name often pops up on lists of neglected and underappreciated novelists. Despite a career spanning six decades and a nomination for the National Book Award (for his 1970 novel, Brill Among the Ruins), none of his books are currently in print. [Amazon reports that Doubleday will be publishing Brill in hardback at $7.95 this month. Probably a data entry error–but if not, grab it! When’s the last time you could get a new hardback copy of a good book for $7.95?] One reason for this lasting reputation, particularly among other writers, was his 23-year stint at the influential Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he mentored numerous young writers of the 1960s and 1970s.

Though Bourjaily wrote The Great Fake Book while in his sixties, the book certainly demonstrates that his appetite for narrative experimentation hadn’t diminished over the years. To tell the dual stories of young Charles Mizzourin and his father, Mike Mizzourin, a newspaperman and jazz musician who died in an auto wreck before Charles was born, Bourjaily uses letters, phone calls, archival documents, oral histories, and even a novel-within-a-novel. He switches decades, narrators, perspective, and tone as fast as Charlie Parker could play changes on “Cherokee.”

Unfortunately, Bourjaily’s experiment is doomed from the onset by unreliable ingredients. The correspondence between Charles Mizzourin and John Johnson (one of the few believable names in the book) that opens the story tries to create the impression of a fencing match between a child of the 60s and a man of the Establishment but just comes off as an inept tussle between two patently made-up stereotypes. We are led to think there is some kind of mystery behind Mike Mizzourin’s death and perhaps also his flip-flopping between journalism and jazz, perhaps having something to do with the Red Scare and McCarthyism–or perhaps not. Frankly, after finishing 100-some pages, I gave up caring and shelved the book. Not, regrettably, before coming across what I truly believe to be the most stomach-turning passage of prose I’ve ever read:

“Hello?”

“Is that my finger-lickin’ chicken?”

“Hello Darlene.”

“Whompsie, did you get an answer from your friend Mr. Johnson?”

“I just found it in the mailbox.”

“I got one, too. To my li’l physical description of you.”

“That right? What’s he say?”

“He sent me his Style Book, and a bill for three dollars.”

“Going to pay?”

“What’s your letter say?”

“I’m about to pour me a drink and sit down with it.”

“Be sure it’s not a letter bomb. You’ll get vodka on your podka.”

“Night, Darlene.”

“Night, light.”

And that’s not the only saccharine attack from Bourjaily’s Kewpie doll creation. I kept hoping Charles would take a lesson from Groucho Marx and warn Darlene, “If icky baby keep talking that way, big stwong man gonna kick all her teef down her fwoat!”

No such luck.

Bourjaily, for a number of years now, has been to my knowledge the last living writer who worked under the editorship of Max Perkins (for his first book; Perkins died just before it was published). He hasn’t published anything that I know of since his last novel appeared 20 years ago.

Just checked out the Amazon page for Brill Among the Ruins, and yes it’s still listed as 7.95, but it’s a bit of a mystery. The publication date is listed as Jan. 2010, and the book is only available as a pre-order item (and the typical used copies as well). Odd.