Jessica Mitford describes Faces of Philip: A Memoir of Philip Toynbee as “A record of events, not purporting to be a complete history, but treating of such matters as come within the personal knowledge of the writer, or are obtained from certain particular sources of information.” With such a qualification, one can excuse the fact that this book is likely to have been of more interest to those who knew Mitford and Toynbee that anyone who might read it then or now.

Philip Toynbee was the son of Arnold Toynbee, the best-known English historian of his time, whose magnum opus, A Study of History, is probably read today by barely more people than read any of his son’s books (all of them now out of print). He and Mitford became friends in the Thirties, when she married Esmond Romilly, with whom Toynbee was working as an anti-fascist activist. Mitford and Romilly moved to the U. S. in the late 1930s and she was stuck there when the war broke out. Romilly joined the Royal Canadian Air Force and was shot down on a mission over Germany and Mitford later married an American, Robert Treuhaft, and became an American citizen herself. Toynbee wrecked his first marriage and married again himself. Through it all, he and Mitford remained friends, writing each other often, seeing each other less often.

As Mitford makes clear without saying it outright, for much of his adult life Toynbee was an alcoholic and perhaps a manic depressive, given to such stunts as stripping to the nude while being returned to his Army unit after a riotous bender in town. But they shared a common sense of affection and fun, as reflected in Toynbee’s letter to Mitford in the late 1970s:

Believe it or not, I’ve just been asked to write your Times obituary. In some ways I see that this is tremendously one up on you–unless, of course, you’ve also been asked to write mine. On the other hand, it does give me a good deal of freedom, doesn’t it: I mean either you’ll never read it, or you’ll read it From Beyond where all is forgiven in every conceivable direction.

All love – and please don’t croak before I get this obit done. Drive carefully for next month or so.

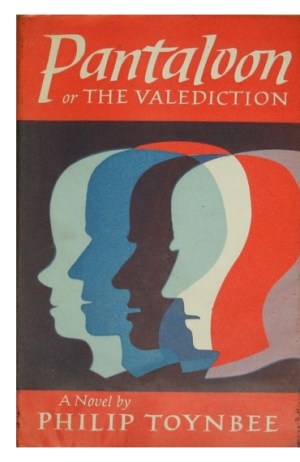

Faces of Philip did offer Mitford the opportunity to pay tribute to Toynbee’s own magnum opus, a series of experimental novels in verse known as “Pantaloon.” Four volumes were published in the 1960s: Pantaloon (1961); Two Brothers (1964); A Learned City (1966); Views from a Lake (1968). As Mitford writes, “These have a small but devoted readership of fellow-poets and critics, some of whom discussed the series in their obituary articles.”

She provides a healthy sample of these assessments of “Pantaloon.” Patrick Leigh Fermor called it a “far-too-little-known, many volumed, and extremely brilliant narrative poem. Far more than a poetical feat of self-mockery, it is a most precious and perceptive documentation of a certain kind of growing-up, with all the problems, trends, dogmatic attractions and revolts to which the restless youth of the middle and late Thirties were prone.” To Stephen Spender, Pantaloon reflects Toynbee’s “serious, religious, ribald, self-mocking attitude to life. His friends will remember him as a poignant and moving personality who lived his life almost as if he were the ironically self-viewing hero of a fiction written by himself.”

Robert Nye, a champion of the experimental in literature, considered it “a remarkable achievement, perhaps a masterpiece…. It strikes me as one of the last authentic works of the spirit of modernism. After Toynbee’s death, Nye wrote that it was “one of the most important landmarks of post-war fiction in England. To re-read the individual volumes consecutively is to realise that here, at last, we have something that can be mentioned in the same breath as A la Recherche.”

In a review of Two Brothers, V. S. Pritchett wrote: “Another important reason for Mr Toynbee’s success is that he has hit on the right subject: the Grand Tour. This cannot fail in the hands of a restless, fervent .and cultivated writer who responds to the gay, the comic and the intense . . . Mr Toynbee has done a very fine thing.” Even The Times’ anonymous obituary writer described it as “A formidable achievement. Even now it is difficult to evaluate it confidently–passages of apparent rambling are juxtaposed with areas of intensely concentrated verbal experience–but it is never less than highly interesting.”

Despite this acclaim, “Pantaloon” has never been reissued and has now been out of print for 50 years. Mitford does mention that as someone who made his living as a book reviewer for most of the 1950s and 1960s, Toynbee took the reception of his own books with ironic humor. “There is only one review worth getting,” he once said. “The one that simply says ‘This is the Best Book Ever Written.'”

A brief excerpt from “The Third Day,” the third chapter in Pantaloon:

Once, in another age or life,

I was standing on the moving-staircase,

Going down.

Wheels and unseen chains were rattling

And feet were scraped on the metal slats of the steps.

Warm air was blown in our faces,

A warm wind breathed up the shaft

From the intricate dark mole-run of the Underground.

The blown air reeked of rubber and sparks

And a mild municipal disinfectant;

Of fagged-out breath and hasty scent,

Warm bodies and clothes.

I welcomed the old smell of a London lifetime.

Faces of Philip: A Memoir of Philip Toynbee is available free in electronic format on the Open Library: Link.

I’ve reached the point where I’m no longer surprised to find that even after decades of looking for neglected books, I can still stumble across completely unfamiliar books and authors. A perfect example is P. B. (short for Patricia Barnes) Abercrombie, who wrote about eight novels, most of them comedies, between the early 1950s and the early 1970s. Angus Wilson once called her “the most interesting of our young women novelists,” and one reviewer called her 1959 novel,

I’ve reached the point where I’m no longer surprised to find that even after decades of looking for neglected books, I can still stumble across completely unfamiliar books and authors. A perfect example is P. B. (short for Patricia Barnes) Abercrombie, who wrote about eight novels, most of them comedies, between the early 1950s and the early 1970s. Angus Wilson once called her “the most interesting of our young women novelists,” and one reviewer called her 1959 novel,

I picked out a yellow-jacketed copy of

I picked out a yellow-jacketed copy of  Yet Oliver La Farge was never one to rest on his family laurels. Instead, he early on discovered a passion for anthropology, and in particular for the native Americans of the Southwest. In his foreword to this collection, La Farge’s

Yet Oliver La Farge was never one to rest on his family laurels. Instead, he early on discovered a passion for anthropology, and in particular for the native Americans of the Southwest. In his foreword to this collection, La Farge’s

I’m pretty sure this is the first book written by a member of the House of Lords I’ve included on this site. I came across

I’m pretty sure this is the first book written by a member of the House of Lords I’ve included on this site. I came across  In my post on Gavin Lambert’s 1959 book,

In my post on Gavin Lambert’s 1959 book,  “The action begins just before Christmas 1956 and ends two years later,”

“The action begins just before Christmas 1956 and ends two years later,”

When

When

And Giles was looking for readers with commitment. A frequent contributor to

And Giles was looking for readers with commitment. A frequent contributor to

When I saw

When I saw  Unlike Dane, who wrote fiction, drama, and nonfiction, Bowen confined herself strictly to writing for children. Although her last book,

Unlike Dane, who wrote fiction, drama, and nonfiction, Bowen confined herself strictly to writing for children. Although her last book,  The next tale deals with Yap, a young fox with still a bit too much fellow-feeling in his heart to realize that the rabbits might not feel quite comfortable with him crashing their Rabbit Fest in a rabbit suit. In most chapters, though, he proves exceptionally adept at team-building. At different times, he joins causes with a toad, a vole, an otter, three badgers, and a hedgehog. The alliances usually seem to involve getting some kind of food, but I guess we don’t have too feel too much remorse over the sacrifice of eggs, fish, or fruit. And when it does involve something a little closer to home, it’s a roast chicken that Yap’s father, Barker Fox, steals from a circus tent, not a live one.

The next tale deals with Yap, a young fox with still a bit too much fellow-feeling in his heart to realize that the rabbits might not feel quite comfortable with him crashing their Rabbit Fest in a rabbit suit. In most chapters, though, he proves exceptionally adept at team-building. At different times, he joins causes with a toad, a vole, an otter, three badgers, and a hedgehog. The alliances usually seem to involve getting some kind of food, but I guess we don’t have too feel too much remorse over the sacrifice of eggs, fish, or fruit. And when it does involve something a little closer to home, it’s a roast chicken that Yap’s father, Barker Fox, steals from a circus tent, not a live one. I found the last tale, “Beetles and Things,” by far the most charming, perhaps because of the illustrations by Harry Rountree (the illustrations for Hepzibah and Yap are by L. R. Brightwell). Montgomery Beetle, in particularly, looks a bit like

I found the last tale, “Beetles and Things,” by far the most charming, perhaps because of the illustrations by Harry Rountree (the illustrations for Hepzibah and Yap are by L. R. Brightwell). Montgomery Beetle, in particularly, looks a bit like