· Excerpt

· Editor’s Comments

· Other Comments

· Reviews

· Locate a Copy

Excerpt

They were six in the crowd. There had been many more before; the entire office. But some of these had stopped being a crowd earlier and began to think for themselves; and, frightened, left the office, and took up their thoughts. But these six that remained, stayed in the crowd, and from then on until late evening, when they were all drunk, and had no thoughts even as a crowd, these six acted together, did things together. When one suggested something to do, they all grasped his suggestion eagerly, and all acted upon it.

There was Bill, who had been the head of the trading room. An older and more intelligent fellow, who should have known better but didn’t. A man with a wife and a child. A man with a future before him. A man who, when he knew where he was going, was as unbent as a steel knife, but when he was broken looked like this same steel knife snapped in two: lost and useless, and good for nothing in the world. A man who should have had somebody to guide him, but who didn’t, and just by a lucky chance had gone as far as he had.

Then there was Blackbird. A braggart. A stupid little fellow. Was always talking about what he had done. Whatever anybody ever talked about had already happened to him. He knew everything. Anyway, he said he did. Contradicted himself in every other word. Shrewd, too. But in a little way. Never had the sense to be large in little ways and clever in big. Anyway, he couldn’t be big. Couldn’t if he had tried to. He was little in everything. And in this little way he was mean.

Ferrari was a wop. Even a God damned wop. With his slick, black hair and long nose. If you didn’t know him you’d say you wouldn’t have liked to meet him at night. He looked like that: tall, and beaky, and not to be trusted. But he was the best telephone clerk on Wall Street. Everybody said that. A holy wonder, this fellow. You couldn’t beat him. And fast! Fast as hell! If he weren’t a God damned wop he’d get somewhere. But you wouldn’t trust him if you’d meet him.

And then there was Eddie: Eddie Drucker. A good fellow. Damned nice fellow. A peach of a guy, a white man. Only a little bit too good. That’s why he wouldn’t go far. He couldn’t. He’d take off his hat, shoes, and underwear and give them to the first person that asked him for them. And he was a bit dumb too. Kind of slow and big. And he wouldn’t have kept this job long if the others hadn’t helped him.

And Charlie. You couldn’t keep a straight face when Charlie was around. They said he could almost make Zuckor laugh. Always cracking jokes and playing tricks, and singing, and raising hell generally. He’d make a funeral laugh.

And finally Phil Johnson. Never say much. Never talk. He’d work like hell, and you wouldn’t know it. Now Ferrari, when he worked, you’d see the feathers flying. Everything with gestures. Stage work. But not Phil Johnson. He was almost as fast as Ferrari, but you’d think he did nothing at all. He didn’t belong in this crowd. He was out of place in it. He should have gone home, and stayed in his little room, and smoked his pipe. That’s what a Swede does. But somehow of other he got into this crowd, and stayed in it, and he was almost as much part of it as Charlie or Eddie.

These six played poker, shot craps, and wanted to fight. And then when they had nothing else to do, they stayed still, slightly out of breath, looking around them.

Then Charlie said:

“Let’s go uptown.”

They said all right. They had been paid off, and their pockets were full with the two weeks’ pay. And they were ready to spend that money. The day before they would not have done it. The day before each one would have said: “This much for rent, this for the grocery bills, and this for the movies.” One or two might have gone into a saloon and bought a drink of whiskey. That would have been all. But this money that they received now, that was all they would get until the next job. And they didn’t think about the next job. They didn’t give a damn what would happen tomorrow. They were a crowd. And they were willing and ready and were going to spend every cent of their money this same evening. They were all going to be broke that night. Tomorrow they would all have to go to the savings bank, or to their relatives, or borrow from their friends, or just go hungry. But they didn’t care about that. They were a crowd.

So they all picked up their hats, and were walking out. And they saw Zuckor. And Charlie being the first wanted to play a joke on Zuckor. He wasn’t afraid of him any more. Like a little boy who on the last day of school tells his teacher to go to hell, wanting to revenge himself for all the wrongs the teacher had committed toward him, Charlie wanted to pay back to Zuckor, to get even with him. So this is what he did: he bowed before Zuckor, tipped his hat, and said:

“Good night, Mr. Zuckor.”

And Blackbird who followed him, also tipped his hat, and said:

“Good night, Mr. Zuckor.”

And Eddie, Phil Johnson, Bill, and Ferrari all did the same: they all tipped their hats to Zuckor and said:

“Good night, Mr. Zuckor.”

This was the worst insult they could think up to show Zuckor what they really thought about him. To show him that before, when they had greeted him, they had never really wanted to. That they had had to do it. Had been forced to. Their job had depended upon their saying, each morning, “Good morning, Mr. Zuckor,” and each evening, “Good night, Mr. Zuckor.” That they had never meant it. That they had never wanted him to have a good morning or a good night. Because he had always been mean and small to them and had wanted to persecute them. Because they had been in his power. He could have made them suffer, go through the agony of being jobless, of not knowing what they would do tomorrow, where their next meal would come from. And he had taken advantage of that, a mean advantage over them, being stronger than they were. So they said to him, “Good night, Mr. Zuckor,” and of all the ways they could have thought up to hurt him, this was the worst way.

They felt that as they were going down the elevator, and they were astonished that they could have thought up such a fine insult. It was more than they could have done had they really thought about it. They didn’t remember who had said it first, but they were glad that they had said it, and even proud of their own cleverness. And thinking of their cleverness made them quiet, not boisterous, as they went down, and as they took a taxi for uptown. They were quiet and dignified, self-conscious of their own cleverness.

Editor’s Comments

The Office is a Wall Street brokerage. In the first three brief chapters of the novel–“Wall Street,” “The Voice of the Office,” and “The Office,” Asch uses a series of impressionistic techniques to sketch his context:

- “Wall Street”:

- New York — downtown — streets — buildings — firms

- buy — sell — exchange — beg — borrow — steal — cheat — give — take — donate — endow — deceive — lie — sympathize — pity — love

- “The Voice of the Office”:

- hey Glymmer I see where Federal Tel went up to par I guess we can let go a few Jacobs get the market on Federal Tel

- zing-ing-ing-ng-g-g

- Mex fours five to a quarter Mexican Irrigation thirty-two to six Mex large five to fifty

- “The Office”

- The office consists of three rooms: one large, one small, and a third cut into smaller cubicles.

- The office gives its employees a living; they work in it and in return they receive pay, for which they buy food, clothing, shelter, amusements, pay the doctor, the undertaker, pay taxes.

… and then one day the office failed …

So Asch titles the second, longer part of the book. Why does the office fail? Asch offers no explanation. The cause is of no special interest. The fact is, the office fails, and suddenly, everyone who works there is out of a job.

Asch’s attention focuses on the immediate impact of the failure, on the thoughts and actions of a cross-section of the people who worked there, from the principal partner to the switchboard operator and the clerks depicted above, in the first few hours after they’re told.

Whatever the cause, the failure comes as a sudden and unexpected shock to almost everyone. In an instant, a fundamental element of each person’s life is wiped out, and the blow sends each reeling. For the clerks, the impact is visceral: they wonder “where their next meal would come from.” One walks down the street, confident in his ability to land another position the next day, until the sight of a vagrant leads him to consider what little separates him, now jobless and with little more than his final pay to his name, from the vagrant’s lot:

He would come in after having long looked for work, looked everywhere and had not been able to find it. Everywhere he came they would look at him and say or only think: “You’re a bum, see? It’s no use giving you work. You’d quit after the first pay-day. You don’t want a job, you only want a meal.” And they’d say, “No, nothing today.”

Another returns home resigned that the loss of her income now dooms her to become a dependent — literally. Without a job of her own, the only alternative she can see is to marry a man she neither loves nor respects:

She was to go home and stay with Jim Denby. She was made for such as he. For men with warm, moist palms, and warm, moist faces, and warm, moist looks. For men who do not take but beg. For sixty dollars a week, and a book-keeper’s household, and a book-keeper’s children, and a book-keeper’s life. Oh, hell!

For others higher up the management chain, the economic impact is multiplied by the social stigma of failure. The principal partner, Glymmer, brought in for his name more than his resources, is a former Treasurer of the United States. A career politician brought up through the ranks by machine politics, he now realizes how little substance stands behind his resume. He has no wealth of his own: he has always lived off his salary. He has no real business acumen to offer, and now that his own firm has failed, his name is only a liability. He is trapped like an animal, and Asch does a stunning job of showing the range of instinctive reactions he experiences as he ride home quietly in the back of his chauffeured limousine.

In his panic, Glymmer latches onto his wife as the source of all his troubles, and he begins to fantasize about how to best humiliate her with the bad news. “You know, we are ruined,” he plans to announce that night at dinner, in front of guests, shattering her world. But something even more fundamental than money and prestige brings Glymmer back to reality:

He had taken the cigar out of his pocket, and was chewing on it, as he always did when he was satisfied with something.

Then, little by little, a look of fright came into his face. His jaw tightened, the cigar fell out of his mouth, and he trembled.

He, he, he, that’s what he would do? That’s what he was doing? Who was he? How could he? Who …

Perhaps I’m reading too much into such a short passage, but I think this is one of several places in The Office where Asch shows a remarkable talent for bringing out depths in his characters with the slightest and subtlest of strokes. Although much of The Office brings to mind the works of his contemporary, John Dos Passos, particularly U.S.A. and Manhattan Transfer, Asch is far more successful in creating three-dimensional characters.

In a few cases, the failure opens an opportunity. One junior partner decides to take his chance as an aspiring writer. Another, the “brains” behind the firm, merely see it as another challenge to be overcome through charm and persuasion:

All around him men trying to get ahead. Men forging ahead. Using all of their wits, all of their powers. Building. Building. Creating new things. Selling. Buying. Exchanging.

And so was he. So was he. He was trying to build too. He also was working.

What if it failed? Other things fail. A man may be down, but he’s never out. And he wasn’t even down. Wasn’t he waiting for the two men to join him for the conference? Wasn’t he going to build a new office? Start things again?

Not all opportunities are taken. Second, skeptical thoughts come and undermine the first optimistic speculations about possibilities and bold choices. In one case — Miss James, the switchboard operator (a wonderfully effective sketch by Asch) — emotions run the full gamut from shock and anger to resignation and disinterest before she even puts on her hat and leaves the office.

Asch wrote The Office in 1925, when business failures were not unknown, but rare. When the Depression hit a few years later, the same experience would be repeated a thousand-fold, but as far as I’m aware, no writer succeeded so well in describing it. FDR’s New Deal introduced a network of social services that provides something of a buffer between the loss of a job and basic survival, but even now, I suspect people would feel many of the same emotions Asch portrays in the first few hours after getting the news. Certain works of literature manage to stay in print because they capture so well something — the death of a child, the loss of faith — many people experience. On this basis alone, The Office deserves to be brought back into print — and kept there.

Other Comments

- • from Conversations with Malcolm Cowley, edited by Thomas Daniel Young, University Press of Mississippi, 1986.

-

Nathan was the son of Sholem Asch, who was an enormously popular Yiddish novelist; all of his books were translated into English and many of them were bestsellers. Nathan started out quite young with a novel called The Office, which received very good reviews here. Didn’t have much sales, most first novels don’t have, but for some surprising reason it sold better in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Then he wrote a second novel that was disappointing to me, called Love in Chartres, and a third novel called Pay-Day, which was more or less suppressed on moral grounds. That was the best of his novels. Pay-Day was also the day of the Sacco-Vanzetti execution, so he worked that into the novel. After that he wrote a book called The Road, about traveling over America by bus, and he wrote a novel about this area, called The Valley. That ended his publishing career. During the war he was a sergeant in the Air Force, really in their public relations, a P.R. non-commissioned officer. Not having to do it, he nevertheless flew a large number, a dozen or more, of bombing flights over Germany, and he wrote letters that were extraordinary. I used to get them. He came back and lived in Mill Valley and wrote, and nothing he wrote was published. Each of his manuscripts would have been accepted if it had been a new book by a new author, but his bad record in the bookstores frightened publishers, and they wouldn’t take his other novels. Then he started to work on memoirs…. He wrote an extraordinary memoir of his father, Sholem Asch, which he gave to Commentary and Podhoretz printed it, after cutting the heart out of it. Then he died of lung cancer. I think he was almost a paradigm of the failed author, but he had loads of talent. He was in Paris with Josie Herbst, another author whom they are making efforts to rescue from obscurity, and John Herman and also Hemingway, who was the great star of Paris in those days….

Reviews

- · Boston Transcript, 14 November 1925

- It is powerfully written. It is swift, relentless. It is New York as people generally conceive New York. It is human nature under the grinding wheels of economic disaster.

- · New Republic, 16 December 1915

- The opening chapter is a sensational accumulation of words. The second chapter carries the method into conversation, and is sensationally effective.

- · New York Times, 11 October 1925

- A Wall Street office of “bucketshop” brokers is evoked by Nathan Asch in sharp, staccato phrases, almost in isolated words. His portrait is completed in less than twenty pages, yet the atmosphere, the nervous tension, the incessant telephoning, the relentless outpouring of tickertape, aimless, meaningless interjections of conversation, and a vague, submerged suggestion of human presences are fully indicated.

“And then one day the office failed.” Thereupon Mr. Asch pursues twenty of the office help, from porter to President, as they wander home or resort to pallid, unimaginative, disheartened efforts at amusement….

His selections are amazingly apposite. He varies his pace and adjusts it unerringly and precisely to the mood he wants to convey. It might be called expressionism in fiction, yet it is not a blind and rigid application of a technical principle. It is fluid and plastic and enormously fresh and stimulating. The effect amply justifies the form.

- • Time magazine, 9 November 1925

- Some staccato words are ripped out. There is The Office: tape, shares, toil, sex, money. The office fails and you go home with the various people whose lives centre in it. A stenographer has to forget the junior partner and marry her boyfriend. The stupid figurehead of the firm trembles, tells his wife. Clerks curse, get other jobs. The junior partner brandishes his cane, plans to run away and be a heman; slinks to his father instead. The crooked partner plans another office. Author Asch seems to know his Wall Street and hate it thoroughly. Striking as an experiment, his book never gets beyond its starting point.

Antoine left with two stretchers, their bearers silent. They went on foot. In the depot at night you have to watch where you put your feet. The ground is full of traps and pitfalls, switch heads, ditches, and engines under steam, a tiny wisp of smoke coming from their stacks. Antoine was thinking. He did not take such deaths very easily. People said, “Accident at work.” And they tried to make you believe that work is a field of honor, while the company provides the widow with a pension, a niggardly pension, it parts with its pennies like a miser, it thinks that death is always overpaid; later it hires the sons of the dead and all is said.

Antoine left with two stretchers, their bearers silent. They went on foot. In the depot at night you have to watch where you put your feet. The ground is full of traps and pitfalls, switch heads, ditches, and engines under steam, a tiny wisp of smoke coming from their stacks. Antoine was thinking. He did not take such deaths very easily. People said, “Accident at work.” And they tried to make you believe that work is a field of honor, while the company provides the widow with a pension, a niggardly pension, it parts with its pennies like a miser, it thinks that death is always overpaid; later it hires the sons of the dead and all is said. There were seven jars attached to the framework in the centre of the room and as soon as the chief’s sons-in-law had arrived and hung up their cross-bows on the beam over the adventures of Dick Tracy, they were sent off with bamboo containers to the nearest ditch for water. In the meanwhile the seals of mud were removed from the necks of the jars and rice-straw and leaves were forced down inside them over the fermented rice-mash to prevent solid particles from rising when the water was added. The thing began to look serious and Ribo asked the chief, through his interpreter, for the very minimum ceremony to be performed as we had other villages to visit that day. The chief said that he had already understood that, and that was why only seven jars had been provided. It was such a poor affair that he hardly liked to have the gongs beaten to invite the household god’s presence. He hoped that by way of compensation he would be given sufficient notce of a visit next time to enable him to arrange a reception on a proper scale. He would guarantee to lay us all out for twenty-four hours.

There were seven jars attached to the framework in the centre of the room and as soon as the chief’s sons-in-law had arrived and hung up their cross-bows on the beam over the adventures of Dick Tracy, they were sent off with bamboo containers to the nearest ditch for water. In the meanwhile the seals of mud were removed from the necks of the jars and rice-straw and leaves were forced down inside them over the fermented rice-mash to prevent solid particles from rising when the water was added. The thing began to look serious and Ribo asked the chief, through his interpreter, for the very minimum ceremony to be performed as we had other villages to visit that day. The chief said that he had already understood that, and that was why only seven jars had been provided. It was such a poor affair that he hardly liked to have the gongs beaten to invite the household god’s presence. He hoped that by way of compensation he would be given sufficient notce of a visit next time to enable him to arrange a reception on a proper scale. He would guarantee to lay us all out for twenty-four hours. In

In

There’s a limit to this respect, though. In fact, we find that horses may have formed a bit too much of Amos’ perspective:

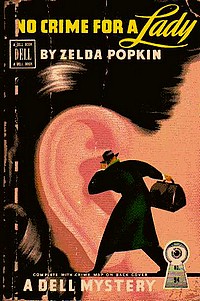

There’s a limit to this respect, though. In fact, we find that horses may have formed a bit too much of Amos’ perspective: In his article, “Judging a Book By Its Cover: 12 Book Designers Who Changed the Publishing Industry Forever,” in the May/June 2006 issue of

In his article, “Judging a Book By Its Cover: 12 Book Designers Who Changed the Publishing Industry Forever,” in the May/June 2006 issue of