George Weller’s Clutch and Differential is an ambitious but ultimately unsuccessful experiment. Indeed, it bears at least one trademark of experimental fiction: an obvious design to which all other elements of the work are subservient. Time magazine’s review provides a good explanation of Weller’s plan:

George Weller’s Clutch and Differential is an ambitious but ultimately unsuccessful experiment. Indeed, it bears at least one trademark of experimental fiction: an obvious design to which all other elements of the work are subservient. Time magazine’s review provides a good explanation of Weller’s plan:

Written in a technique that owes something to John Dos Passos, something to James Joyce, Clutch and Differential is made up of 35 long episodes dealing with characters who bear little apparent relation to each other. Stripped of its complicated gadgets, it could be mistaken for a collection of old-fashioned, high-wheeled short stories. But 18 of George Weller’s episodes are subtitled “clutch” and 17 “differential” and apparently the clutch stories deal with people who are hanging on to money, love or dreams, while the differential ones deal with people who are letting go. Each “clutch” episode is introduced with a little discussion called Shift of Gear and followed by one called Universal, made up of technical automotive instructions directly or obliquely related to the material of that particular episode.

In addition to the alternation of his “clutch” and “differential” motifs, Weller adds the constraint of arranging the stories in order of the age of their protagonists: the first story, “Irene Herself,” is written in the voice of a girl of about 5; the last, “Mark My Words,” in that of Julia, an aging widow somewhere past seventy.

Weller places his overall theme at the book’s start, quoting a supposed automobile sales circular that states, “Beneath American-made bodies that are tastefully refashioned every year, power transmission has gained a standard performance. New bodies come and old bodies go but clutch and differential now change but little.” The message that human nature persists despite changes in technology has become more familiar since 1936, but even then it was a slender branch on which to hang a 400-plus page magnum opus.

Weller deserves an E for effort. He strenuously embraces and attempts to project the unique voice of each of his characters, whether it’s a clueless high school football player missing his first chance at making out to a passed-over Foreign Service officer musing over his many failures to make the right career moves. And you can’t help but admire his breadth of vision, as he ranges all over the social and geographical map of the United States.

Unfortunately, all this good work comes to no great end. One finishes story after story wishing Weller had applied his impressive techniques to a character or situation of real substance and interest rather than an theoretical construct. None of the 35 Americans in Clutch and Differential is half as believable as any of Joyce’s Dubliners and certainly none of its stories comes close to an “Araby” or “Two Gallants,” let alone “The Dead.” In all his earnest design and construction, Weller forgot to include some heart and soul.

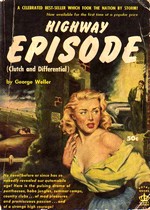

Clutch and Differential was reissued as “Highway Episode” in an early paperback edition that featured a woman in stereotypically-ripped bodice fleeing from some unknown threat, alongside text that claimed, “No novel before or since has so nakedly revealed our automobile age! Here is the pulsing drama of penthouses, hobo jungles, summer camps, country clubs … of mad pleasures and promiscuous passion ….” It was also reissued for the academic market in 1970.

Weller went on to work as a journalist during World War Two and after, earning a Pulitzer Prize in 1943 for an account of an emergency appendectomy performed on a submarine in enemy waters. He died in 2002, but his work will soon be in print again, thanks to his son Anthony’s compilation of his father’s long-withheld account of the devastation of Nagasaki, First Into Nagasaki — which has already sparked some contrarian comments in his Wikipedia bio.

Thank you for sharing these insights. I gather the line of writers who felt Bennett Cerf’s editing seriously damaged their work would have run a good Manhattan block or more.

I’m also glad to hear that my comments didn’t send you off in search of a good hit man. Personally, I’m a big fan of experimental fiction. By definition, it doesn’t always have to succeed–in fact, in some ways, the way you measure the success of an experimental work is more in terms of how big a jump away from conventions it takes and less in terms of how well it lands. By this standard, it was a big success.

Thanks again for posting.

Congratulations on unearthing my father’s second novel, originally published by Random House as “Clutch and Differential” in 1936 and as the lurid paperback above around 1953 — trimmed by a mere 30 pp., which did little to solve the novel’s drawbacks.

In hardback, despite strong (if somewhat puzzled) reviews, it sold only 697 copies, earning him a whopping $207.19. This cured him of novel-writing for a dozen years. He always spoke bitterly about publishing an experimental novel in the heart of the Depression — “just what people standing on bread lines couldn’t wait to read.”

I cannot find in his papers any information on how the misleadingly racy-covered paperback sold; and when I showed him a copy, at age ninety he had no recollection of its existence. He’d have been overseas as a war correspondent when the deal was struck by his agent, and maybe he never saw it.

I don’t think he would disagree with your assessment of the novel, and he always spoke of it being damagingly waylaid by his own quest for a perfection of form (youth to old age, etc.).

The automobile-as-metaphor-for-American-life, however, was not his idea, but that of his editors at Random House, Bennett Cerf and (I believe) Horace Gregory, who pushed those linking passages / divisions on him to begin each chapter. He regretted their intrusion most strongly, even a half-century later, and regretted giving in; he thought the artificial device ruined the novel, in fact. Alas, I don’t know what his original title was.

— Anthony Weller