“I’m not ashamed of anything I’ve ever done. You don’t get to be big without pulling a couple of fast ones. That goes for anybody. A big man is a fast man.” This quote is blazoned across the top of the paperback edition of Benjamin Appel’s A Big Man, a Fast Man, along with two contrasting views of a man: the “Big Man” addressing a crowd of men; the “Fast Man” contemplating a buxom brunette in a slip.

When I start to read an old paperback with a garish cover like this, I always wonder: Is it going to better than the cover–or worse? I think it’s safe to say that a lot of what got published back in the 1950s and 1960s in paperbacks with such teasing covers is worse.

In this case, however, it’s quite a bit better, and not just because the cover’s pretty tame by the standards of the time. A Big Man, a Fast Man is the story of Bill Lloyd, a veteran labor organizer and now president of the United Suppliers Terminal Workers, a union with over 800,000 members. Lloyd’s union is under Federal investigation for corruption. The union’s founder and past president, Art Kincel, recently committed suicide and the head of the East Coast branch was found dead under suspicious circumstances.

Seeking a little relief from all the negative publicity, Lloyd approaches a public relations firm in search of some “dramatic publicity” to distance him from his predecessors. His ideas: a TV series, articles in the Saturday Evening Post, or “an autobiog similar to best-sellers on movie stars/other glamourites.” So one of the firm’s execs sits Lloyd down and lets him tell his life story while the tape recorder is rolling and the rye is flowing.

This aspect of the novel already distinguishes it from the run of the mill. The book consists of six tape transcripts, framed by a series of short memos from the exec to the firm’s head. It’s also a discontinuous narrative, as each tape deals with different periods of time–the current controversies; Lloyd’s childhood as the son of a coal miner; his rise in the union after World War Two; his experiences as an organizer in the steel and warehousing industry.

Appel demonstrates a certain amount of art in his sequencing of Lloyd’s recollections. By his own account, his hands are fairly clean, at least as far as the current problems go. But we also learn that one of the reasons the union was in trouble was that Kincel had been colluding with industry management to downplay worker unrest in return for substantial baksheesh. And that Lloyd himself had seen this sort of backstage dealing on a smaller scale when first working for the union in the 1930s.

As Appel plays out the story, Lloyd went into the labor movement out of inspiration by a few idealistic early organizers, but somewhere along the way, he chose to favor realism over idealism:

It was too much for me, worn out like I was. A fellow can’t stay up on that cross forever. Got to be a Jesus to do that. I tried to calm her down, but go calm down a fanatic. She had her religion even if it was a red one with a red Jesus. What I did was go for the bottle of rye…. Think too much of what a world this is and you go nuts.

Even though he proclaims, “I stayed in the labor movement. I stuck to my principles. By God, I stuck,” you get the strong sense he’s flailing. The audience most in need of some positive publicity is Lloyd himself. Overall, Appel is effective in capturing the tone of a man becoming disoriented as he wanders through his past. Some of it’s the booze, but more of it is Lloyd’s own struggle to understand just how he got to where he is now.

Overall, A Big Man, a Fast Man is better than the average novel of its time, if not quite a significant piece of literature, and certainly better than that cheesy cover.

A Big Man, a Fast Man

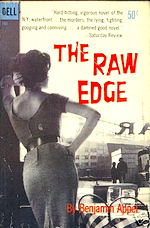

A Big Man, a Fast Man is one of two novels wrote in the late 1950s about the labor movement. The other, The Raw Edge

dealt with the conflicts and corruption of the Longshoreman’s Union in New York City, the same territory explored by Elia Kazan in “On the Waterfront.”

Appel’s career as a writer spanned five decades and his work ranged from serious fiction such as A Big Man, a Fast Man

Appel’s career as a writer spanned five decades and his work ranged from serious fiction such as A Big Man, a Fast Man to a series of children’s history books with titles like We Were There in the Klondike Gold Rush

and science fiction satires such as Funhouse

.

His best known work, Brain Guy, is the story of a smart, business-minded gangster, into crime and real estate–rather like a 1930s version of Stringer Bell from “The Wire.” Stark House Press reissued it a few years ago, packaged in volume with Plunder

, a 1952 novel about G.I. hustlers in the Philippines. And earlier this year, Stark House reissued two more hard-boiled Appel novels from the 1950s, Sweet Money Girl and in one volume.

Find a copy

- Find it at Amazon.com: A Big Man, a Fast Man

- Find it at Amazon.co.uk: A Big Man, a Fast Man

- Find it at AddAll.com: A Big Man, a Fast Man

I will check this book out…