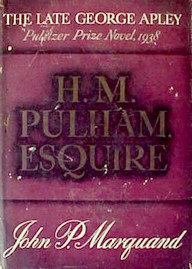

If Ford Madox Ford hadn’t already used the line, I might say that this is the saddest story I have ever heard. And there are at least a few strong parallels between H. M. Pulham, Esquire and Ford’s masterpiece, The Good Soldier. Both novels are related in the first person by unreliable narrators–unreliable primarily due to the incredible strength of the cultural and social blinders they’ve grown into–and both narrators are utterly oblivious to the fact that their wives are having affairs with men they consider good friends.

Compared to Ford, however, Marquand is more craftsman than artist. His prose style is never much more than workmanlike, and he has at time a tendency to fill pages more for the sake of providing his audience with a good thick read than for shaping his story. But observation, not artistry, is Marquand’s long suit. He is an ideal observer–a novelist of society, perhaps America’s best after Edith Wharton. Like Wharton, he is both immersed in society, having been raised in family highly sensitive to–if not highly placed in–Boston society, and able to detach himself and note its many ironies and shortcomings. And H. M. Pulham, Esquire

Compared to Ford, however, Marquand is more craftsman than artist. His prose style is never much more than workmanlike, and he has at time a tendency to fill pages more for the sake of providing his audience with a good thick read than for shaping his story. But observation, not artistry, is Marquand’s long suit. He is an ideal observer–a novelist of society, perhaps America’s best after Edith Wharton. Like Wharton, he is both immersed in society, having been raised in family highly sensitive to–if not highly placed in–Boston society, and able to detach himself and note its many ironies and shortcomings. And H. M. Pulham, Esquire is a perfect example of what he could accomplish at his best.

Pulham, gives us a year in the life of Harry Pulham, graduate of St. Swithins School for Boys (think Choate or Andover) and Harvard as he nears 50. Roped into organizing his college class’ 25th anniversary reunion, he narrates the book as one long contemplation on what he’s going to tell his classmates about the course his life has taken.

In his time, Marquand was considered a satirist, but his sensibilities are far more nuanced than that. One could read Pulham, and conclude that Harry Pulham is a one-dimensional man utterly lacking in irony. I use irony here in the sense so well discussed recently by Roger Scruton: “a habit of acknowledging the otherness of everything, including oneself.”

After all, the result of a year’s worth of Pulham’s meditations is a vapid piece for the reunion book with such stereotypical statements as, “I do not believe that either Mr. Roosevelt or Germany can hold out much longer and I confidently look forward to seeing a sensible Republican in the White House.” And, even more strikingly, after being everything but told outright that his wife and best friend have been having an affair, he writes that he “never regretted for a moment” his marriage “since our life together has always been happy and rewarding.”

What is remarkable about Marquand’s accomplishment, though, is how deftly he manages to bring out a number of subtexts in Pulham’s apparently superficial narrative. One is the story of a life defined by the road not taken–the advertising job in New York City he left to return to Boston when his father fell ill, the attractive and challenging woman (“a good deal more of a person than I was, more talented, more cultivated”) he fell in love with and left behind as well. Pulham has based most of his most important choices on what was expected of him:

Romantic novelists have created the illusion that it is hard to find someone to marry. From my own observation I think they are mistaken. There is nothing easier than doing something that nature wants you to do, and there is always someone ready to help you. Before you know what it is all about, you are selecting cuff links for the ushers.

Nature, in Pulham’s case, is society, specifically the proper social elite of Boston. Being a member of that society means belonging to the right clubs, sending your children to the right schools, summering in the Maine isles, and conforming to a narrow pattern of behavior:

I met Cornelia Motford at the Junior Bradbury Dances, the second series that started close to the cradle and ended in the vicinity of the grave. In fact, only two years ago Cornelia and I were asked to subscribe to the Senior Bradbury Dances. If we had accepted we would have seen the same faces that we had seen at the Baby Bradburys almost thirty years before.

Another subtext, then, is the story of a man whose life was defined for him. Of course he married a girl from his own class, a girl he’d know socially since childhood: what else could he do? How could he describe the confines of his life as a prison or straitjacket if there were no other choices offered him?

But if Harry Pulham is not a cardboard conservative, neither is he a pathetic victim. and this is not the saddest story I’ve ever read. Probably the thing I like most about Marquand’s books is how remarkably grown-up a writer he is. He understands that the number one reason you don’t chuck it all in and run off with the secretary or your old girlfriend or rebuild your life from ground up is that it would hurt the people you love.

Pulham is not completely lacking in introspection. He might write to his rah-rah classmates that “life together has always been happy and rewarding,” but to himself he has the capacity to admit, “It might have been better for us both if we had been frank instead of nursing a sort of reticence, and a fear that one would be defenseless if the other knew too much.”

It’s hard to believe, for example, that Pulham is not well aware of the tongue-in-cheek humor of the following:

I was never reminded so much of death as I was when we were engaged. There were certain pieces of furniture that we could have now, but it was necessary to remember that there were lots of other pieces–rugs and sofas and tables and pictures–which we would have when Mother and Mrs. Motford died. When Mrs. Motford died we could have the large Persian carpet with the Tree of Life that was in the parlor. When Mother died we could have the Inness, and it would be much better to plan on having these things some day; and yet when we actually did plan, both Mother and Mrs. Motford would always resent it. They would say that Kay and I talked as though they were dead already, and neither of them was going to die just to please Kay or me; and once Mother said that I wanted her to die, and Kay told me that Mrs. Motford had said the same thing.

And throughout the novel there are wonderful little moments when Marquand gives us wonderful little glimpses into Pulham’s awareness of his own passage through time:

We came into Providence, and the car grew dark and gloomy because of the train shed over it. Then it moved out into the afternoon and the cold rays of the sun came through the left-hand windows and I saw the state capitol. Once long ago when we had to change cars at Providence on the way to some place like Naragansett Pier, Mother had taken Mary and me into the capitol, and we stood in the rotunda, looking at the flags brought back from the Civil War. I might pass that building a thousand times without ever setting foot in it again.

OK, À la recherche du temps perdu this ain’t, but neither is it Babbitt. Pulham

is a rich and realistic account of one man and the society and world he lived in by a man with a rich sense of irony. I remember thinking when I read The Good Soldier

, “This would be considered a tour-de-force of narrative voice if it were being published today,” and I often had the same thought while reading H. M. Pulham, Esquire

. Once again, I have to say that with Marquand’s being out of print and out of favor, a very respectable and interesting body of work is being unjustly neglected.

Find a Copy

- Find it at Amazon.com: H. M. Pulham, Esquire

- Find it at Amazon.co.uk:

- Find it at AddAll.com:

<

fyi: The prep school is Groton

Thanks for the comment. Actually, before the Mr. Moto novels, Marquand was hugely successful as a writer of short stories for magazines such as Collier’s and the Saturday Evening Post. I haven’t read Point of No Return, but I can certainly recommend So Little Time and B. F.’s Daughter. Sincerely, Willis Wayde, which I’ve written about on this site, is a lesser work but also worth the time.

Yes, I read H. M. Pulham, Esq. a few weeks ago and I agree with all you say. Marquand is not a great novelist, but is a very good one (and, as is the case with so many neglected mid-century authors) much better than many current authors who are considered good. You don’t mention the strange and perhaps unique shape of Marquand’s career: he was a successful popular novelist (creating the detective character “Mr Moto,” played in a series of films by Peter Lorre) as well as a “literary” writer (thus Marquand’s next book after H. M. Pulham [1941] was Last Laugh, Mr Moto [1942]). A biography by Stephen Birmingham called The Late John Marquand was published in 1972 and can be found on Alibris, etc. I’ve not read that yet, but I’ve read several other Marquands: The Late George Apley (1937), which is good, but seems like a sketch for what M. was to do in later books); Wickford Point (1939), which I greatly enjoyed and which has one of those wonderful character-sketch openings Marquand does so well, this time depicting a pretentious literary scholar); and Women and Thomas Harrow (1958), a late book in which he seems to have gone off a bit, and is certainly covering old ground. (Randall Jarrell in one of his essays says that Marquand wrote the same book over and over again “the story of a man who is haunted by his past, but realises he could not have changed it” and that may be true, but at its best it’s a good book. The negative case against Marquand is put more forcefully in Walter Allen’s Tradition and Dream: Allen sees Marquand as a writer who promises much, but never delivers, which I don’t think is fair.) I’m told that Point of No Return (1949) is one of Marquand’s best novels.