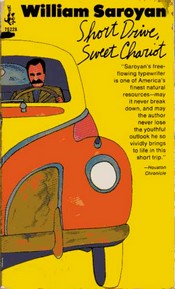

“In the summer of 1963 I bought a 1941 Lincoln limousine in New York, so that I might be chauffeur in California to the few remaining dignitaries in my family,” William Saroyan explains at the start of Short Drive, Sweet Chariot

“In the summer of 1963 I bought a 1941 Lincoln limousine in New York, so that I might be chauffeur in California to the few remaining dignitaries in my family,” William Saroyan explains at the start of Short Drive, Sweet Chariot. This slim book is his account of his trip to Fresno, accompanied by his cousin John, to take his uncle Mihran and other relatives out for rides in style. Or rather, his account of part of that trip. The part from Ontario to the edge of South Dakota, where Saroyan cuts to the chase and a short postscript saying, in effect, “So anyway we got to Fresno and took Mihran out for a drive.”

This is Saroyan at the point in his career where he’d just about given up any pretence about sticking to any particular literary form, when most of his work consisted of perambulating, wise-cracking monologues. For a few fans who truly love his idiosyncratic meanderings for the loose, baggy messes they are, these books are Saroyan in his purest, most brilliant form. For most of the reading public that had made early books such as The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze best-sellers, a book like Short Drive, Sweet Chariot

wasn’t worth noticing.

Personally, I kinda prefer these latter messy books. I still have a copy of his last book, Obituaries, from 1979, which was nominated for an American Book Award and helped–a bit–to restore Saroyan’s critical reputation. Obituaries

has the structure of an entry for each day of the day, with each entry discussing someone whose obituary appeared in a paper that day. However, more than a few entries start out along the lines of, “So-and-so died today. I never met him. There was another guy I knew, though, and he ….”

But you don’t read one of these books because Saroyan follows the rules, you read it because he’s almost always at least interesting and occasionally brilliant, funny, poetic, or tender. And when he’s not … well, the momentum along will carry you and him along to the next good bit. Like this little meditation:

In getting from Windsor to Detroit there is a choice between a free tunnel and a toll bridge, which turned out to be a short ride for a dollar, which I mentioned to the toll-collector who said, “One of those things,” impelling me to remark to my cousin, “Almost everything said by people one sees for only an instant is something like poetry. Precise, incisive, and just right, and the reason seems to be that there isn’t time to talk prose. This suggests several things, the most important of which is probably that a writer ought not to permit himself to feel he has all the time in the world in which to write his story or play or novel. He ought to set himself a time-limit, and the shorter the better. And he ought to do a lot of other things while he is working within this time-limit, so that he will always be under pressure, in a hurry, and therefore have neither the inclination nor the time to be fussy, which is the worst thing that happens to a book while it’s being written.

Or this one about the precedent Kennedy set as the first Catholic elected President:

President Hamazasp Azhderian, that’s the man I’m waiting to see in office. I’d like the order to be about like this, for the purposes of equity. After the Catholic, a Jew. Then, a twice-married, twice-divorced beautiful woman, known to be fond of bed and gazoomp. Then, a Negro, preferably very black. Then, a full-blooded Blackfoot. And finally Hamazasp Azhderian.

C’mon now–wouldn’t it be cool to have “a twice-married, twice-divorced beautiful woman, known to be fond of bed and gazoomp” after President Obama?

“Americans,” Saroyan writes, “have found the healing of God in a variety of things, the most pleasant of which is probably automobile drives.” Short Drive, Sweet Chariot is certainly one writer’s celebration of the pleasures of driving a fine vintage automobile along the mostly pre-freeway roads of America, but in Saroyan’s case, there doesn’t appear to be anything he needed to be healed of. More, it was a golden opportunity to expound for hours on end to a capture audience–namely, his cousin John. John comes off as an intelligent and enormously patient man who only occasionally finds it necessary to burst one of his cousin Bill’s bubbles.

And fortunately, cousin Bill was a pretty interesting guy to listen to. No, Short Drive, Sweet Chariot is no masterpiece and not much more than a bit of intelligent, poetic, meandering fluff. But it’s also an entire work, in the sense that Saroyan used that word: “incomplete, impossible to complete, flawed, vulnerable, sickly, fragmented, but now, also, right, acceptable, meaningful, useful, and a part of one larger entirety after another, into infinity. Kind of a modern age equivalent of the Great Chain of Being.

You’ve given me an appetite to go try on another of Saroyan’s later books.

actually, i doubt if saroyan ever “made his money” — since he was a gambler, and gambled huge amounts of money away, just like that. so he made a precarious living there, towards the end, i’m sure. but his writing had always been free-form. much of the success of “the daring young man on the flying trapeze” was based on the fact that someone simply wrote two pages of text, and bam. that was it. pure poetry, or just letter-writing or a page from anybody’s journal. but it was alive.

when it came to writing ordinary novels (“rock wagram”) saroyan no longer measured up, but a good deal of the bits in between was still recognisably saroyanesque. i imagine the ultimate saroyan sampler will not bother with such descriptions of his style as “sentimental”. it will simply recognise the fact that saroyan articulated his awareness of being alive, and we have those verbal photographs. as we look at them in some sequence, they seem to tell a story, but the story is not the most important aspect. what is important is that realisation that we all have of “myself upon the earth.” that little book up there is very much of that sort, a series of snap shots taken at a certain time, and then abandoned. what’s it about? it’s about sitting in a car and driving across a piece of the USA. talking, picking up a hitch-hiker. driving an old car. and finishing the book before you finish telling the story. it’s great.

Thanks for the comments. Saroyan is certainly sentimental and I’d have to agree with you that the books they keep reprinting are great–if you’re a big fan of “The Waltons.” What I like about Saroyan is that–after he made his money with “The Human Comedy,” “The Time of Your Life” and other works in the early 1940s, he just kept on writing–whatever he felt like, apparently, and much of it the same kind of stream-of-consciousness commentary/observations/memories/stories/lies that fill this short book. You gotta give him credit for moxie, if nothing else.

i read this book once — and enjoyed it. it taught me something about travel writing — as i guess it did to the guy who wrote “fear and loathing in las vegas”, ha ha. it would have made a nice piece in some magazine, along with some photographs — eg, vanity fair. maybe somebody will find half a dozen pictures and still print it in — vanity fair.

i’ve got a bunch of ancient saroyan books i’m busy reading just now, e.g., “three by three” — some of these things are pretty messy — but then they’re almost 70 years old and a lot of literature is no longer readable after that length of time. i picked up “the man with golden arm” by nelson algren which i believe was the best book of its year — 1949, or 1951 — and you could see that it was a good book and well-written, but still, quite unreadable. not anywhere as alive anymore as the movie — and there you get a sense that sinatra really WAS on dope to play his bit, convincingly.

i guess saroyan will continue to be read for some years yet, but not all of it, not all of his stuff. it’s like charles bukowski came along and picked up on saroyan, but left the mushy bits out. but bukowski’s not necessarily a better writer, he’s just a little closer to our own time. give it another 50 years, i imagine you’ll get a volume of saroyan’s stories and stuff — and a volume of bukowski’s — standing side by side.

i still enjoy reading saroyan, but there’s a lot of his stuff which don’t even have — and it’s almost impossible to find — and i don’t really trust the taste of those people who keep republishing “human comedy” and “aram” — as if that was all that mattered about him. there’s no serious saroyan scholarship — so all you get is well-meaning private opinions. pity.

Thanks for the comments, Robert. Always a treasure trove of information. I think a small book shelf could be filled with books related to Saroyan’s divorce. You can add in son Aram Saroyan’s “Trio” from 1985.

Also, it’s worth mentioning that the very first book review Michael Dirda, the Pulitzer-winning former books editor of the Washington Post, ever published in that newspaper was of the second-to-last book Saroyan published in his lifetime, Chance Meetings. Dirda panned it – indeed, I’ve read it and remember nothing about it except that it directed some bitter, barbed words at his ex-wife Carol, as was the case with most of his later books. (Carol herself published two remarkable books – The Secret Of The Daisy, a novel written as Carol Grace, and Among The Porcupines, a memoir under her later married name of Carol Matthau.)

I read Short Drive, Sweet Chariot about eight or nine years ago, at a time when I was reading a half-dozen of Saroyan’s late volumes of fragmentary memoirs. (Days Of Life And Death And Escape To The Moon has the most memorable title, but at the moment I can’t recall if I read that one or not.) The one thing in Short Drive that’s really stuck in my mind is what Saroyan wrote in it about the death of Hemingway. Writing and death are Saroyan’s two driving, obsessive, intertwined themes after the mid-1950s, up to his death – just as they were during the same years for a writer seemingly very different from him, Maurice Blanchot. (Indeed, one of the most perceptive things ever written about Saroyan was an essay by Blanchot in the 1940s – it’s been translated into English, but I don’t remember which book it’s in.)

Heyday Books, a California press, published a huge anthology of Saroyan’s writings to mark his 100th birthday last year, with an introduction by Herbert Gold, who knew the writer in his last decades. But the anniversary went more or less unnoticed outside California and the Armenian-American community, except for an essay in The Weekly Standard.