A while ago, The Denver Bibliophile wondered why I didn’t cover more neglected thrillers. The simple answer is that I’ve never been a big fan of thrillers, perhaps out of a long-standing aversion to best-sellers in general.

But his comment did get me thinking that there might just be something worth finding if I could look past this prejudice. So while I was rooting through the stacks of the wonderful Montana Valley Book Store in little Alberton, Montana, about a half hour west of Missoula–probably America’s best book store located in the middle of nowhere–I decided to pull a few lurid titles from the terrific stash of old paperbacks in the basement.

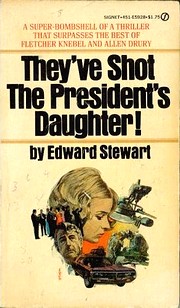

I couldn’t resist starting in with the most ridiculous title in the bunch: They’ve Shot the Presidents Daughter!

I couldn’t resist starting in with the most ridiculous title in the bunch: They’ve Shot the Presidents Daughter!, by Edward Stewart. “A Super-Bombshell of a Thriller that Surpasses the Best of Fletcher Knebel and Allen Drury!” proclaims the cover. At the time, this meant something to potential buyers. Thirty-plus years later, those names either mean nothing or (in Drury’s case) great lumps of pedestrian prose.

But within the first couple of pages, it became quite clear that this was something other than a typical thriller. It opens with the President, the First Lady, and a nameless general riding in a limousine out to Andrews Air Force Base for a trip on Air Force One. Stewart describes the scene through the eyes of the First Lady, and her perspective is hardly what you might expect from the usual stereotypes that populate such books:

And as happened from time to time lately, when she sat in a closed space near her husband, she could neither slide away from him nor summon any thought of her own strong enough to war off the even-edged blade of his voice. And it seemed to her, no disrespect intended, that these litanies of problems and crises and billions (of dollars, she supposed), there proposals and rejections that were whispered at her elbow, these schemes and tragedies and intrigues that fell from his lips in ever so slightly mocking a monotone were–though enough–for him only mantras, aids in meditation, ways of getting his mind off petty aches and woes that would have submerged him if he had ever tried to cope.

They’ve Shot the Presidents Daughter! takes place in a post-Nixon America (at one point the Vice President is seen reading Nixon’s memoirs), but an America dealing with most of the same problems: race riots, student protests, and a dirty war (this time in Costa Rica). President “Lucky Bill” Luckinbill–tall, steely-jawed, with blue eyes and greying temples–comes straight from Central Casting, but seems mostly ineffectual. Kissinger is gone, but one Nahum Bismarck has taken his place at the President’s right hand. J. Edgar Hoover is gone, too, along with the F. B. I., but in their place are now one Woodrow Judd (whose Watergate apartment features paintings of his favorite poodles) and the Federal Security Agency. John and Martha Mitchell have been replaced by Vice President Howard Tyson and his talkative and media-struck wife, Maggie (who’s also more conniving and ambitious than the worst Republican stereotype of Hillary Clinton).

And political assassinations involving ex-C. I. A. men are still the stuff of the best conspiracy theories. The trip the First Couple are taking is to the President’s home town of Whitefalls, South Dakota, where he will lay a wreath on the grave of his mother. While the President is offering some token remarks, a lone gunman in a nearby church steeple shoots his daughter Lexie, sitting on the dais.

There is some panic and a rush to the nearest hospital, but Lexie proves to be only slightly wounded. The gunman disappears without a trace. The President seems unable to respond and the incident soon becomes a source of satiric attacks on the Administration.

At this point, Stewart takes a long and seemingly tangential detour in the narrative. He introduces Frank Borodin, a burned-out agent in the Federal Security Agency, who is assigned to read through hundreds of letters intercepted in the Whitefalls post office in search of clues about the gunman. We read along with Borodin through letter after letter of utterly mundane material, most of it from one Darcy Sybert, a sad young woman who’s recently disappeared from the town:

I’ve just discovered casseroles and the meat grinder, which means that not much gets thrown out in the way of food–there are so many different ways of serving leftovers, things that even Mom didn’t discover! Sometimes in the kitchen I feel like Christopher Columbus–I guess Dad and Bobby do too when I bring out the dinner. Last night we had “supreme de supreme” (my own name for it), soft of a cauliflower and pork hash thing in jellied chicken soup.

Gradually, though, Borodin picks up a thread that leads him from Darcie to Hiram Judd, another F. S. A. postal inspector, who’s also disappeared, and eventually follows it back to Washington and some high-level people in the Administration. At this point, Stewart starts switching the reader rapidly through a variety of perspectives–the First Lady spinning into ever-higher reaches of paranoia; Maggie Tyson–the Second Lady–fomenting right-wing fury on television; several Senators pushing through a gun control bill with a rider giving Congress the right to suspend the Bill of Rights; Lexie Luckinbill falling in love with one of her Secret Service men.

This last brings out some priceless bad popular novel prose from Stewart:

And then they snapped together like two ropes yanked into a knot. The breath was crushed from her lungs and her heart hammered at her ribs as though to break an opening and fly out. Her eyes half shut and she stared into his, seeing herself bent and reflected as in the lens of a camera, and silently, with fierce, entreating telepathy, she dared him, begged him, commanded him.

The mechanical integrity of Stewart’s narrative also leaves a lot to be desired. At a certain point, he begins slapping on pieces like a roofer before a thunderstorm, more interested in finishing the job than in getting the shingles well placed. For most of the book, I was willing to tolerate the slipshod construction because of the regular and bizarre excursions into the First Lady’s mind:

The First Lady had spent her married life mired in the type of syllogism the senator was trying to force on her now. The reasoning seemed logical, it seemed right even, but if you looked closely you saw that terms kept shifting their meaning and premises were as shaky as condemned buildings; and now that she had crawled out, she had no intention of crawling back and letting the beams fall on her head. She did not care much for logic when the conclusion of every argument was do my bidding. War must end–do my bidding. Taxes are high: the poor are rebelling; your daughter may die–do my bidding.

They’ve Shot the Presidents Daughter! ends with a grand operatic scene in the Senate chamber that’s inept, implausible, and unconvincing, but Stewart loses control of his own book well before this point. As thrillers go, it’s average at best, and for much of the book, the narrative tension is slack. If I’d been reading for the story, I’d have given up soon after Frank Borodin starts wading through Darcie Sybert’s letters (“Guess what–I passed biology!”).

To me, the interest–the fascination, almost–of the novel was in the interior monologues of Monica Luckinbill and a few other characters. Borodin, for example, remembering how his marriage fell apart:

He had begun noticing small things, dust building up on the window ledges, smudges on the panes that seemed to indicate a face had been pressed against them. He had once found a half-finished letter in the typewriter, left there perhaps for him to find; and because it was part of his work and he was training to read other people’s mail he read it, even though his sense of self-preservation told him not to; and the letter said, I spend most of my time moping, but at least I have a decent stereo.

There are wonderful little passages like this through much of the book, things that could almost have come out of a Raymond Carver story. It’s as if Stewart wanted to write something very odd, dark, and ironic, but felt bound to slap together something the reading public might take for a political thriller. It’s easy to tell where his heart was in his work and where it wasn’t.

As a whole–and certainly as what it was marketed to be–They’ve Shot the Presidents Daughter! is a failure. But I’m glad The Denver Bibliophile prodded me to take a closer look at a few thrillers, because in this case, at least, I discovered a few gems scattered among the fodder.

Stewart, years before, had written a satirical, picaresque novel called Orpheus on Top c. 1966 which my mom loved. I finally read it some years later and found its satire pretty heavy and sort of harsh beyond the author’s years, but I could see why a kind of male version of Candy like this had been shockingly new and naughty then (my mom being in her own mid-20 then even if she already had me and seemed much more grownup then than I did at a similar age).

Thanks, Robert. I do remember seeing Anderson’s article but couldn’t locate it again. I can’t share his opinion, though. There is certainly a black streak, in the sense that it proves to be the President himself who masterminds the conspiracy to kill his daughter. But the politics in the book seemed heavy-handed and if Stewart’s tongue was in his cheek, he did a great job of hiding it. I honestly would have rather seen what he would have turned out if he’d written as a straight novel of character and perspective and left the task of creating a driving narrative to someone else.

This novel by Stewart, who died in 1997, has its fans. In the article below, Patrick Anderson, a veteran thriller writer who’s been reviewing books in this genre every Monday in the Washington Post for many years (and who published a book-length study of the genre in 2007 or so) argues that it’s a sharper satire of the Nixon era than Philip Roth’s far better-known Our Gang.

http://www.washingtonian.com/articles/people/5940.html