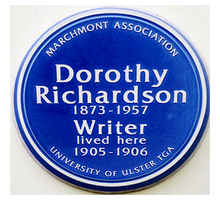

I recently embarked upon my longest voyage into the sea of neglected women writers, a journey through the thirteen volumes and over two thousand pages of what is easily the most neglected great serial novel, Dorothy Richardson’s Pilgrimage. I am a little late, by this site’s standards, in coming to read Richardson, who, according to a Guardian article published last May, is finally receiving the recognition she deserves.  The article came out the day a Blue Plaque in her honor was unveiled in Bloomsbury, at the address where she lived during 1905 and 1906, marking the centenary of the publication of her first novel, and the first book in Pilgrimage, Pointed Roofs. She has her own website, run by Professor Scott McCracken, who is also the lead editor for the Dorothy Richardson Scholarly Editions Project launched by Keele University, which plans to release annotated editions of all of Richardson’s works over the course of the next decade. Broadview Press released scholarly editions of Pointed Roofs and the fourth novel in the series, The Tunnel, in 2014, an online exhibition of her letters was opened a few months ago.

The article came out the day a Blue Plaque in her honor was unveiled in Bloomsbury, at the address where she lived during 1905 and 1906, marking the centenary of the publication of her first novel, and the first book in Pilgrimage, Pointed Roofs. She has her own website, run by Professor Scott McCracken, who is also the lead editor for the Dorothy Richardson Scholarly Editions Project launched by Keele University, which plans to release annotated editions of all of Richardson’s works over the course of the next decade. Broadview Press released scholarly editions of Pointed Roofs and the fourth novel in the series, The Tunnel, in 2014, an online exhibition of her letters was opened a few months ago.

However, while a complete scholarly edition of Richardson’s work may become available ten years from now, today the situation is little better than it was fifty years ago, when Louise Bogan wrote, “Merely to get at Dorothy Richardson’s novels … has, of late, become so difficult that the waning of her reputation may be partly put down to the absence of her books themselves and data on their author.” The best complete edition, issued in four volumes by J. M. Dent in 1967, goes for $250 and more, if you can find it. For about $50, you can assemble the four paperback volumes issued as Virago Modern Classics in 1979, but they tend to be “well read” copies. There was also a cheap paperback set published by Popular Library in the U. S. in the 1970s, but it’s more of a wreck than a reference. I decided to compromise, picking up the four volume set published by Knopf in 1938, in excellent condition from John Schulman’s Caliban Books, supplemented with the VMC volume 4, which includes the posthumous thirteen novel, March Moonlight. However, I’ve also provided links below to free electronic editions of the first seven novels, courtesy of the Internet Archive.

And it’s very appropriate to devote a month to Richardson during this (second) year of exclusively reading the works of women. For Richardson was never anything but ferociously her own person, and that person was most definitely female. As Derek Stanford wrote in an obituary piece in 1957, “In all the two thousand pages of Pilgrimage there is not one effort to see the world from a man’s point of view.” Pilgrimage was, for Richardson, more than a work of fiction. Indeed, much of what occurs to Miriam Henderson, the heroine of the novels, is what happened to Richardson. The places, events, and characters can almost all be traced to their real counterparts in her life. As Horace Gregory wrote in his marvelous introduction to her work, Dorothy Richardson: An Adventure in Self-Discovery (1967), “To reread Pilgrimage today is to recognize that this particular work of art is closer to the art of autobiography than to fiction.”

In this series there is no drama, no situation, no set scene. Nothing happens. It is just life going on and on. It is Miriam Henderson’s stream of consciousness going on and on…. In identifying herself with this life which is Miriam’s stream of consciousness Miss Richardson produces her effect of being the first, of getting closer to reality than any of our novelists who are trying so desperately to get close. No attitude or gesture of her own is allowed to come between her and her effect.

Writing to an inquiring reader some thirty years after beginning Pilgrimage, Richardson was a little uncomfortable with the “autobiography” label but most definite that what the books weren’t was fiction:

If by “autobiographical” you intend the telling of the story of a life, then, though all therein depicted is dictated from within experience, Pilgrimage is certainly not an autobiography. Nearer the mark, though too suggestive of “science” in the narrowed, modern application of that term, would be “an investigation of reality.” The term novel as applied to my work took me by surprise; but I did not then know what was beginning to happen to “the novel.

Vincent Brome, who was the last person to interview Richardson, shortly before her death in 1957, tried to capture what she described as the experience of writing the books: “She would feel herself surrendering to the consciousness of what seemed to be another person, to look out on that brilliant world, awaiting the final metempsychosis … until all signs of self-consciousness vanished and she was no longer herself; and then disconcertingly, it seemed to her that this other world had identities with a buried self dimly apprehended in states of reverie. Her plunge had become a plunge into her own unconscious.” When she reached this point, Richardson said, the writing flowed, accompanied with “a sense of being upon a fresh pathway.”

Indeed, in the final volume of Pilgrimage, March Moonlight, Miriam/Dorothy defined writing as a form of establishing reality from her reflections:

While I write, everything vanishes but what I contemplate. The whole of what is called “the past” is with me, seen anew, vividly… It moves, growing with one’s growth. Contemplation is adventure into discovery; reality. What is called “creation,” imaginative transformation, fantasy, invention, is only based on reality. Poetic description a half-truth? Can anything produced by man be called “creation?”

Richardson, asserted Louise Bogan, “is not recounting it to us retrospectively; she is sharing it with us in a kind of continuous present. Not this is the way it was, but this is the way it is.” And it is this quality that makes Pilgrimage vibrant and enthralling reading even a hundred years after it was written.

And so, we set out on Dorothy Richardson’s voyage to discovery her own reality. There is no better synopsis that the one provided by Bogan in her review of the 1967 J. M. Dent complete edition:

[W]e finally have Richardson through “Miriam” complete: the brave, if not entirely fearless (for she is often racked by fear), little wrong-headedd-to-the-majority partisan of her own sex (and of living as experienced by her own sex), in her high-necked blouse and (before she took up cycling) long skirt, from which the dust and mud of the London streets must be brushed daily; working endless hours in poor light at a job which involved physical drudgery as well as endless tact; going home to a tiny room under the roof of a badly run boardinghouse; meeting, in spite of her handicapped position, an astonishing range of human beings and of points of view; going to lectures; keeping up her music and languages; listening to debates at the Fabian Society; daring to go into a restaurant late at night, driven by cold and exhaustion, to order a roll, butter, and a cup of cocoa; trying to write, learning to write; trying to love andyet remain free; vividly aware of life and London. And continually sensing transition, welcoming change, eager to bring on the future and be involved with “the new.” And reiterating (on the verge of the most terrible war in history, wherein all variety of masculine madnesses were to be proven real): “Until it has been clearly explained that men are always partly wrong in their ideas, life will be full of poison and secret bitterness.”

Pilgrimage, by Dorothy Richardson

Individual Novels

- Pointed Roofs (1915 Duckworth edition, 1919 Knopf edition with introduction by May Sinclair; also on Project Gutenberg)

- Backwater (1916 Duckworth edition, 1919 Knopf edition)

- Honeycomb (1917 Duckworth edition, 1917 Knopf edition)

- The Tunnel, (1919 Duckworth edition, 1919 Knopf edition)

- Interim (1919 Duckworth edition, 1920 Knopf edition only available through the Hathi Trust)

- Deadlock (1921 Duckworth edition, 1921 Knopf edition)

- Revolving Lights (Only 1923 Duckworth edition available online)

- The Trap, London: Duckworth, 1925; New York: Knopf 1925 (Not available online)

- Oberland, London: Duckworth, 1927; New York: Knopf 1928 (Not available online)

- Dawn’s Left Hand, London: Duckworth, 1931 (Not available online)

- Clear Horizon, London: J.M. Dent & The Cresset Press, 1935

Collected Editions

- Pilgrimage (4 volume set), London: J. M. Dent and Cresset Press, 1938 (included an 12th novel, Dimple Hill published for first time)

- Pilgrimage (4 volume set), New York: Knopf, 1938 (includes Dimple Hill)

- Pilgrimage (4 volume set), London: J. M. Dent, 1967 (includes a 13th novel, March Moonlight, which was published posthumously)

- Pilgrimage (4 volume mass market paperback set), New York: Popular Library, 1976 (includes Dimple Hill and March Moonlight)

- Pilgrimage (4 volume trade paperback set), London: Virago, 1979 (includes Dimple Hill and March Moonlight)

Thanks for the comment. As you can see from my own posts, DR’s work proved the most illuminating reading experience I’ve had in years, and I can only hope we can collectively raise her work and her reputation up to the level of recognition it deserves. Over three months after finishing Pilgrimage, I’m still comparing everything else I read to it, and that’s a tough mark for many other books to measure up to.

Once again, I’m indebted to you for another fantastic recommendation. When I kept seeing post after post about this book in March, I added to my list and then promptly got lost in other projects. I should have made this my priority, because DR has captivated my imagination and fired me up. Truly amazing, and I’m only 3 books in!