Ida Maria Luise Sophie Frederica Gustave, daughter of Carl Friedrich Graf (Count) von Hahn, married her wealthy and elderly cousin Friedrich Wilhelm Adolph Graf von Hahn, and thus became Ida Maria Luise Sophie Frederica Gustave, Gräfin (Countess) von Hahn-Hahn, giving all of us the pleasure of a small chuckle. The marriage was unhappy and they divorced less than three years later. She took it in mind to be a writer and proceeded to produce several books of poetry and then a string of novels “depicting, in a very aristocratical manner, the manners of high life in Germany,” according to Sarah Josepha Hale’s Woman’s Record.

Ida Maria Luise Sophie Frederica Gustave, daughter of Carl Friedrich Graf (Count) von Hahn, married her wealthy and elderly cousin Friedrich Wilhelm Adolph Graf von Hahn, and thus became Ida Maria Luise Sophie Frederica Gustave, Gräfin (Countess) von Hahn-Hahn, giving all of us the pleasure of a small chuckle. The marriage was unhappy and they divorced less than three years later. She took it in mind to be a writer and proceeded to produce several books of poetry and then a string of novels “depicting, in a very aristocratical manner, the manners of high life in Germany,” according to Sarah Josepha Hale’s Woman’s Record.

And she took it in mind to become a traveller. According to Hale’s account of her life, Countess Hahn-Hahn went to Switzerland, Austria, Italy, Spain, France, Sweden, England, Central Europe, Turkey, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt over the course of roughly ten years, after which she retired to a convent to meditate, pray, and write devout books.

The only point in mentioning her here is that her collections of letters from her trips to France, Spain and the Near East were considered exceptional by the reviewers of their English translations. Of course, exceptional is a double-edged adjective: “The merits and demerits of her writing are so interwoven that it is hard to pronounce upon them without being unjust to the one or far too lenient to the other,” wrote one. Yet, “In liveliness of observation, readiness of idea, and spirited ease of expression, she is unsurpassed by any lady writer we know,” wrote another. Male readers seem to have delighted in her frank opinions, which she felt free to express with vehemence even though it seems pretty clear that she expected her correspondents to hang on to her letters so she could publish them after returning from her journeys. Her writings were held to have “an air which is not ill-described by the term insolent. Saucy is hardly strong enough. Exceedingly saucy women, however, when they happen to be pretty, witty, and well-informed, are often agreeable companions, and almost always pleasant correspondents.”

The countess was certainly capable of painting a pleasant word picture when offered the right scene. Here, for example, is life on the streets of Pesth (the eastern side of Budapest):

People do not merely walk—they sit, work, sleep, eat, and drink in the street. Almost every third house is a coffee house, with a broad verandah, around which are ranged sophas and blooming oleanders. Incredible quantities of fruit, grapes, plums, particularly melons, and heaps of water-melons, are offered for sale. Unemployed labourers lie, like lazzaroni, on the thresholds of their doors or on their wheelbarrows, enjoying the siesta. Women sit before the doors, chatting together and suckling their infants. The dark eyes, the loud, deep voices, here and there the piercing eyes, are all southern.

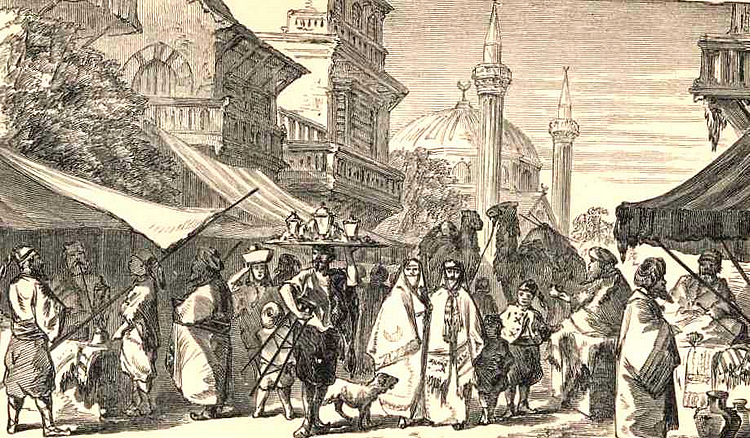

Here she offers us the streets in Constantinople in all their anarchic glory:

If none but dogs were the inhabitants of Constantinople, you would find it sufficiently difficult to make your way through a city where heaps of dirt, rubbish, and refuse of every credible and incredible composition, obstruct you at every step, and especially barricade the corners of the streets. But dogs are not the only dwellers. Take care of yourself — here comes a train of horses, laden on each side with skins of oil — all oil without as well as within. And, oh ! take care again, for behind are a whole troop of asses, carrying tiles and planks, and all kinds of building materials. Now give way to the right for those men with baskets of coals upon their heads, and give way, too, to the left for those other men — four, six, eight at a time, staggering along with such a load of merchandise, that the pole, thick as your arm, to which it is suspended, bends beneath the weight. Meanwhile, don’t lose your head with the braying of the asses, the yelling of the dogs, the cries of the porters, or the calls of the sweetmeat and chestnut venders, but follow your dragoman, who, accustomed to all this turmoil, flies before you with winged steps, and either disappears in the crowd or vanishes round a corner.

At length you reach a cemetery. We all know how deeply the Turks respect the graves of the dead — how they visit them and never permit them to be disturbed, as we do in Europe, after any number of years. In the abstract this is very grand, and when we imagine to ourselves a beautiful cypress grove with tall white monumental stones, and green grass beneath, it presents a stately and solemn picture. Now contemplate it in the reality. The monuments are overthrown, dilapidated, or awry — several roughly paved streets intersect the space — here sheep are feeding — there donkeys are waiting — here geese are cackling — there cocks are crowing — in one part of the ground linen is drying — in another carpenters are planing — from one corner a troop of camels defile — from another a funeral procession approaches — children are playing — dogs rolling — every kind of the most unconcerned business going on.

She was vocal in her dislike for the manners of a minor member of the Ottoman nobility who travelled on the same ship with her to Constantinople: “If you had anything in your hand that attracted the pasha’s notice, an operaglass, for instance, or a telescope, he beckoned to one of his slaves, and the slave instantly took the opera-glass, or whatever it might be, out of the hand of the owner, and delivered it to his master. He examined it, tried it, and when he was tired of it, he gave it back to the slave and the latter to the owner. Some chose to consider this behaviour simple, childlike, engaging; for my part, I could only think it rude….”

Nothing so attracted her disdain, however, as the French. Her beloved papa fought alongside von Blücher at Waterloo, and she never forgave his people for raising up the upstart from Corsica. “I shall now go to France, Heaven knows what the consequence may be, for I hate France! I hate the spirit of vanity, fanfaronade, insolence and superficialness; in short, I hate the national character of the French. It is unmitigated barbarism.”

Needless to say, her letters from France are less saucy than venomous.

According to various sources, something close to a half-dozen of her collections of travel letters were translated and published in English, but today, only a couple of partial volumes can be found. Google has volume 1 of her Letters of a German countess; written during her travels in Turkey, Egypt, the Holy land, Syria, Nubia, etc., in 1843-4; the Internet Archive has volume 2; I haven’t found volume 3 yet. I haven’t found any others in the Internet Archive, but I may not be looking hard enough.

This does sound interesting. I’m not sure I’ll ever make time to read it, but I hope I do.