Excerpt

In my year as a newspaper reporter I have interviewed several other prominent men, but they were as chaff blown in the wind. Probably the most famous of these was Admiral George Dewey, hero of Manila Bay.

Admiral Dewey was here to make a speech and I interviewed him at Hotel Lafayette. He is scarcely taller than I, but quite bulky. He seemed pompous and imperious. I did not like him.

I tried to talk to him about the destruction of the Spanish fleet in the Philippines.

“Everybody knows about that,” he blurted. “Happened eight years ago. Every school child knows all about it. Silly to write anything more.

“What the papers need to print is that Admiral Dewey says we need a bigger navy. Write that. Write that Admiral Dewey says we need more ships and more men. We’re rich and we can afford it.”

I said, “Admiral, don’t you think we have a pretty good navy now?”

He twisted one prong of his big white mustache and glared at me. When he is thinking about something else Admiral Dewey is a rather placid and comfortable-looking man. But he fancies himself as a fierce old sea dog. So he looked fierce at me and growled, “Pretty good! Fellow, I’ll have you understand the United States has got the best navy in the world.”

“Well,” I asked, “why, then, do we need a bigger navy?”

He shook his head in disgust. “We’ve got to have a still bigger navy because we’re the richest nation on earth. The whole world is healous of us. And we’ve got to keep them afraid. But one of our American ships is equal to two of most nations’. Take our enlisted men. They’re all young Americans. You know what that means?”

“Well,” I said, “I suppose–”

He interrupted me. He hadn’t asked the question to find out what I thought. He wasn’t a bit interested in what I thought about anything. He made that quite plain.

“It means,” he said, “that if all the offiers in the fleet were killed the enlisted men could fight the ships and do it successfully. The United States navy takes only the cream of the nation’s youth.”

He looked me up and down pointedly. “The navy will take no skinny, undersized men. A man lacking in bodily vigor is usually lacking in mental vigor. The navy wants only those young men who may work up to command. A man has got to be well-nigh perfect physically before he even gets by the recruiting officer.”

Of course I was there to meet a great man and to get an interview, but it seemed to me he was making a deliberate attempt to affront me because of my physical limitations. So I looked him up and down pointedly also. And I said, “I presume, Admiral, that must be a rather recent ruling?”

My sarcasm was lost. “Not at all,” he said, “not at all. That ruling has been a tradition with the United States navy. It used to be iron men and wooden ships. Now it is steel men and steel ships.”

Comments

Great American Novel is the journal of a newspaper reporter and editor over the course of nearly 40 years. Early on, he falls in love with a girl in his neighborhood, but through a silly misunderstanding, comes to think she has spurned him and takes off for another town in spite.

He never does reunite with her. He ends up marrying and having children, but continues throughout his years to fantasize about the love that might have been. In the end, he learns that she has died, having married after–probably–giving up hope for his return.

Davis tries to make an ironic point about his protagonist living the Great American Novel through all the years that he kept meaning to sit down and write one. And he does manage to convey a pretty vivid account of American life from the 1900s to the late 1930s. But there isn’t much beef to the Homer, his lead character, so perhaps Davis’ joke is on us as much as on the protagonist.

Review

Time, June 6, 1938:

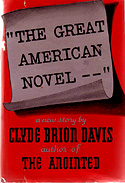

A solemn sap, scrawny, cartoon-faced Homer Zigler was a 23-year-old, $1-a-week cub reporter on a Buffalo newspaper when he decided to become a novelist. But first, said Homer, “to the purpose of preparing myself for that career,” he would keep a journal. “The Great American Novel—” is the journal—a satire that starts off by tagging after Ring Lardner, turns off on an oily road marked Irony-&-Pity, skids into caricature, and comes to a happy halt as the June choice of the Book-of-the-Month Club—as did Author Davis’ first novel, The Anointed, a bare ten months ago.

Homer’s dogging muse is his blonde sweetheart, Fran, who “is sure I shall become a novelist of the Irving Bacheller type—which is exactly the goal at which I am aiming.” When the next best-seller type appears, he aims at it (“I can learn much of style from David Grayson,” he writes). In 1936, 30 years later, his aim is still waving around, but he hasn’t fired a shot. He just goes on filling his journal with fatuous, trite, sentimental, philistine, ingenuous, graphic practice notes: about newspaper jobs in Cleveland, San Francisco, Denver, everything from news happenings to a synopsis of his novel (a stupendous family chronicle from Jeremiah I to Jeremiah IV), from election returns to querulous data on his wife’s raising the baby on candy, from denunciations of automobiles and airplanes to pompous credos favoring Democracy. Typical of his talent is his alibi for hanging around his Kansas City landlady’s daughter: “When a man denies himself all feminine companionship,” reflects Homer, “he is likely to warp his cosmos.”

The really important entries in Homer’s journal, recurring about once a week, are his dreams of his old sweetheart Fran. These dreams start soon after he runs away from Buffalo, jealous because she talked to another boy. Homer believes his visions are mystic bulletins telling in exact detail what happens to her; he is, of course, 100% wrong. When, in one of them, Fran’s clothesline breaks, Homer writes severely: “I should think Clark [her dream husband] could at least put up a wire clothesline for her.”

Toward the last third of the journal, when Homer is in his 40s, he begins reading Sherwood Anderson, Dreiser, Hemingway, confesses that his “whole attitude toward literature is undergoing a renascence.” When, despite his sobered new outlook, he continues right up to his sudden end to be almost as dumb as ever, most readers will call his story a libel on even the most fatuous of would-be novelists.

Will add this novel to my website about Buffalo fiction and link to you.