As she travels with her father from England through Holland to Germany, Miriam swings back and forth between eager anticipation at the novelty and adventure of her first time in foreign countries and grave doubts about whether she is up to the challenge. Her willingness to go it on her own is helped along to some extent by her irritation at her father’s attempts to glorify the situation:

He was standing near her with the Dutchman who had helped her off the boat and looked after her luggage. The Dutchman was listening, deferentially. Miriam saw the strong dark blue beam of his eyes.

“Very good, very good,” she heard him say, “fine education in German schools.”

Both men were smoking cigars.

She wanted to draw herself upright and shake out her clothes.

“Select,” she heard, “excellent staff of masters… daughters of gentlemen.”

“Pater is trying to make the Dutchman think I am being taken as a pupil to a finishing school in Germany.” She thought of her lonely pilgrimage to the West End agency, of her humiliating interview, of her heart-sinking acceptance of the post, the excitements and misgivings she had had, of her sudden challenge of them all that evening after dinner, and their dismay and remonstrance and reproaches–of her fear and determination in insisting and carrying her point and making them begin to be interested in her plan.

After a long train ride through Holland and northern Germany, they arrive in Hanover, where her father leaves Miriam at a school run by Fräulein Lily Pfaff in a large house near the old part of town (whose medieval half-timbered houses and roofs inspired the title of this chapter). The school had about a dozen boarding students, a mix of German and English girls between the ages of 8 and 14 — barely younger than Miriam/Dorothy herself, who was just 17 when she came to the school. Typical of the educational approach for such girls at the time, Fräulein Pfaff’s curriculum is a mix of language instruction (German, French, English), singing and piano lessons, sewing, and religious training by a Lutheran pastor, with many idle hours and occasional outings. Perfect preparation, in other words, for a life as the well cared-for and placid wife of a comfortably rich man.

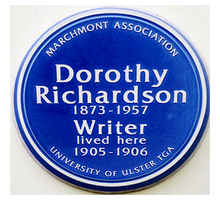

I am indebted–and will be throughout the rest of these posts on Pilgrimage–on George H. Thomson’s A Reader’s Guide to Dorothy Richardson’s Pilgrimage (1996) and his Notes on Pilgrimage: Dorothy Richardson Annotated (1999). The former provides a detailed chronology of the narrative events, the latter identifies and explains the many otherwise cryptic references in the text and reveals the depth to which his research took Thomson into such esoterica as card games, popular songs, railway routes and fares, and London shops of the period (1893-1915) covered by the books. In addition, Gloria Fromm’s Dorothy Richardson: A Biography (1977) is invaluable in providing a key to the ways in which characters, places, and events in Miriam Henderson’s life do — and do not — mirror those of Richardson’s.

With the help of Thomson and Fromm, for example, we can identify that Fräulein Pfaff’s real-life counterpart was Fräulein Lily Pabst, who ran the school at 13 Meterstrasse (Google Maps) in Hanover at which Richardson taught in the first half of 1891 (two years earlier than Miriam). According to Fromm’s biography, Richardson did not realize until halfway through writing the book that she had been using the real names of her characters, when she changed Pabst to Pfaff. In some cases, she never did come up with fictional alternatives.

As one might expect for a girl barely out of school herself and with no formal training or preparation to teach, Miriam is filled with doubts. Even before she leaves home, she dreams of being rejected by her students: “They came and stood and looked at her, and saw her as she was, without courage, without funds or good clothes or beauty, without charm or interest, without even the skill to play a part. They looked at her with loathing.” Riding through Germany, she looks out at the night as anxious thoughts run through her mind:

It was a fool’s errand . . . to undertake to go to the German school and teach . . . to be going there . . . with nothing to give. The moment would come when there would be a class sitting round a table waiting for her to speak. . . . How was English taught? How did you begin? English grammar . . . in German? Her heart beat in her throat. She had never thought of that . . . the rules of English grammar? Parsing and analysis…. Anglo-Saxon prefixes and suffixes … gerundial infinitive…. It was too late to look anything up.

And while she never does lose those doubts, Miriam manages to charm her girls with her youth and enthusiasm for the experience. However, she also quickly realizes that she is temperamentally incapable of going along quietly with a curriculum designed to produce passive and unquestioning helpmates. She seethes inside as the girls have a simplistic Lutheran dogma drilled into their heads and are led off to spend hours at services at the local church. She begins to realize how exceptional — if still imperfect — was her own schooling, which encouraged girls to think beyond marriage as a future: “the artistic vice-principal — who was a connection by marriage of Holman Hunt’s and had met Ruskin, Miriam knew, several times — had gone from girl to girl round the collected fifth and sixth forms asking them each what they would best like to do in life.” Tellingly, Miriam’s prompt response was, that she wanted to “write a book.”

Pointed Roofs introduces us to two themes that will remain constant throughout Pilgrimage: the role of music and clothes in Miriam’s world. For Miriam and her sisters (like Richardson, she has two older and one younger sister), music is an essential part of their lives. A piano and a rich collection of sheet music is the centerpiece of the family’s living room, and they all spend hours playing and singing, by themselves, with family, and for parties. Musical references account for a considerable share of Thomson’s annotations. In just the first 100 pages, Miriam thinks of, plays, or hears The Mikado, “Abide with Me,” Don Giovanni, Lohengrin, Chopin nocturnes, Beethoven sonatas, Mendelsohn’s Spring Song, and songs from the period like “Beauty’s Eyes,” “Venetian Song,” and “In Old Madrid.”

And there are her clothes. Miriam is lucky enough to have avoided the worst of the days of corsets and stays, but the awkwardness of women’s clothing of the time and the shabbiness, age, and poor quality of her own is an irritation never too far from her mind. Walking out in the chill of one of her first days in Hanover, she catalogs the shortcomings of her English clothes:

She hated, too, the discomfort of walking thus at this pace through streets along pavements in her winter clothes. They hampered her horribly. Her heavy three-quarter length coat made her too warm and bumped against her as she hurried along–the little fur pelerine which redeemed its plainness tickled her neck and she felt the outline of her

stiff hat like a board against her uneasy forehead. Her inflexible boots soon tired her.

Her family’s effort to supplement her wardrobe don’t help, either: “‘We are sending you out two blouses. Don’t you think you’re lucky?’ Miriam glanced out at the young chestnut leaves drooping in tight pleats from black twigs … ‘real grand proper blouses the first you’ve ever had, and a skirt to wear them with … won’t you be within an inch of your life!'” As Pilgrimage progresses, Miriam’s struggles to deal with cheap shoes, dowdy blouses, and skirts that show all the stains and marks of daily wear in a working world are reminders of the meager circumstances to which her poorly-paid jobs condemn her, and the fine dresses and hats she sees other women in are symbols of a power and privilege she can never aspire to.

Miriam’s enthusiam for her German adventure carries her through the worst days, but she unwittingly earns Fräulein Pfaff’s criticism: “You have a most unfortunate manner,” the school mistress tells her. “If you should fail to become more genial, more simple and natural as to your bearing, you will neither make yourself understood nor will you be loved by your pupils.” Though Miriam would like to stay on at the school, she runs into a simple financial predicament when they arrive at the summer holiday period. Two of the girls invite her to join them and their families at the North Sea, but she simply lacks the money to cover the expense of her lodging and food. And Fräulein Pfaff makes little effort to encourage her to stay. Just five months after coming to Hanover, Miriam boards a train to return to England, knowing she may never come back to Germany again.

Pointed Roofs superbly introduces us to Richardson’s style, viewpoint, and journey. Miriam is still awakening, still naïve, and still tentative in her engagements with the adult world, but she already has a strong sense of an inner drive that will not easily accept the conventions of her day. In its very first paragraph, Richardson tells us that contemplation is as essential to Miriam’s being as breathing: “There was no one about. It would be quiet in her room. She could sit by the fire and be quiet and think things over….” As Walter Allen wrote in his introduction to the 1967 J. M. Dent collected edition, the first complete edition of the novel, “Pilgrimage shows us, uniquely, what it felt like to be a young woman, ardent, aspiring, fiercely independent, determined to live her own life in the profoundest sense….” Having just passed the halfway point through Pilgrimage, I think it may represent the high point so far in my year-plus exploration of the world as seen through the eyes of women writers.