Every writer who’s ever been featured on Oprah’s Book Club follows in the footsteps of Alexander King. When he published his memoir, Mine Enemy Grows Older

Every writer who’s ever been featured on Oprah’s Book Club follows in the footsteps of Alexander King. When he published his memoir, Mine Enemy Grows Older in 1958, he was, in the words of a Time magazine reviewer, “an ex-illustrator, ex-cartoonist, ex-adman, ex-editor, ex-playwright, ex-dope addict.” His book probably would have taken a quick trip to the remainder tables–had it not been for a lucky and path-setting break: on the second of January, 1959, King appeared on “The Tonight Show”, hosted by Jack Paar, to plug his book. As Russell Baker put it years later, “After charming millions on the Jack Paar show, Alexander King came up out of the basement and took off like a 900-page bodice ripper.”

Mine Enemy Grows Older is King’s rambling and very much tongue-in-cheek account of his first fifty-some years. Born in Vienna (as Alexander Koenig), King emigrated with his family to New York City in his teens. With a little bit of art training and a great deal of moxie, he worked his way through dozens of jobs, from decorating department store windows and painting murals a Greek restaurant to illustrating radical newspapers.

It was as an illustrator that King’s career finally took off. Throughout the 1920s, he was caught up in the convention-flounting wave of Mencken, The Smart Set, and the Jazz Age and became a much-in-demand illustrator for new, unbowdlerized editions by such scandalous authors as Flaubert, Rabelais, and Ovid. He then worked as an art editor, first for Vanity Fair and then for Henry Luce’s transformed Life magazine. Unfortunately for King, he developed a serious kidney problem that led to a doctor’s prescribing morphine as a pain killer.

It was as an illustrator that King’s career finally took off. Throughout the 1920s, he was caught up in the convention-flounting wave of Mencken, The Smart Set, and the Jazz Age and became a much-in-demand illustrator for new, unbowdlerized editions by such scandalous authors as Flaubert, Rabelais, and Ovid. He then worked as an art editor, first for Vanity Fair and then for Henry Luce’s transformed Life magazine. Unfortunately for King, he developed a serious kidney problem that led to a doctor’s prescribing morphine as a pain killer.

At the time, morphine was controlled but legally available in pill form from most pharmacies. And like any addictive drug, it also encouraged a thriving black market, with shady MDs writing scrips on demand for junkies like King who could scrape up enough cash. Eventually, King’s addiction led to his being arrested and convicted on federal drug charges and sent to a narcotics rehabilitation hospital in Lexington, Kentucky. He was able to clean up, get back into painting, and reestablish some of his connections with the publishing world in New York, which led to a contract from Simon and Schuster for Mine Enemy Grows Older.

It probably would have ended there had not King’s wry and outrageous banter on Paar’s show. He was just the sort of taboo-breaker Paar’s audience was looking for: funny, opinionated, unconventional, urbane. Frank and April Wheeler of Richard Yates’ Revolutionary Road would have loved him. Take this account of King’s reaction to being stuck in a room in Lexington with nothing to read by an issue of the Saturday Evening Post:

It was a waking nightmare of the most sinister dimension and variety. My whole past life was insidiously evoked, ruefully demonstrated, and mercilessly indicted. It suddenly came to me that the reason my three marriages had smashed up was, simply, that they had been frivolously ratified on the wrong kind of mattresses; I realized with unshakable conviction that my social and financial calamaties had been caused by my improperly sanitized apertures; and, as I went on reading, it became brutally clear that all through my life I had washed only with soap substitutes, had worn unmasculine underwear, and had never decently neutralized my offensive bodily effluvia.

For seventy-two hours I wallowed in accusations and self-reproaches, and when the nurse finally let me out of my isolation cubicle I was a psychic tatterdemalion.

I remember saying to the doctor who interviewed me that rather than have another such weekend, I would prefer to spend three days on an army cot, lashed to a belching, gonorrheal Eskimo prostitute, who had just finished eating walrus blintzes.

Funny stuff, for sure. Practically every page of Mine Enemy Grows Older is filled with this sort of caustic, ribald bird-flipping humor. For fifteen to twenty minutes on a talk show it must have seemed like revolutionary stuff. By the end of the book’s 374 pages, however, it has grown monotonous and tiresome.

That didn’t stop Simon and Schuster from releasing four more books by King between 1960 and his death in 1965: May This House be Safe from Tigers (1960); I Should Have Kissed Her More

(1961); Is There A Life After Birth?

(1963); and Rich Man, Poor Man, Freud, and Fruit

(1965). All sold well, though each time in diminishing numbers. There was something about King that really appealed to readers and viewers at the time. My grandparents, life-long Republicans and firm upholders of middle-class values, had two of his books on their shelves, and kept them with the small number they moved to their retirement apartment. Nor did it keep Paar and then Johnny Carson from bringing him back for dozens of appearances.

My theory is that King’s was a safe form of revolt. He mocked convention, but he didn’t exactly offer an alternative–nor did he suggest that people grab torches and set fire to police stations. He was like a Brother Theodore who could write. He introduced America to the term, “raconteur” and opened a door for other talk show guests–including Truman Capote. After a long day at the office and an evening of westerns and sitcoms, a bit of King’s “acid appraisals of modern art (‘a putrescent coma’), advertising (‘an overripe fungus’) and people in general (‘adenoidal baboons’)” (to quote Time’s obit of King) was a refreshing bit of outrage before turning in for the night.

My theory is that King’s was a safe form of revolt. He mocked convention, but he didn’t exactly offer an alternative–nor did he suggest that people grab torches and set fire to police stations. He was like a Brother Theodore who could write. He introduced America to the term, “raconteur” and opened a door for other talk show guests–including Truman Capote. After a long day at the office and an evening of westerns and sitcoms, a bit of King’s “acid appraisals of modern art (‘a putrescent coma’), advertising (‘an overripe fungus’) and people in general (‘adenoidal baboons’)” (to quote Time’s obit of King) was a refreshing bit of outrage before turning in for the night.

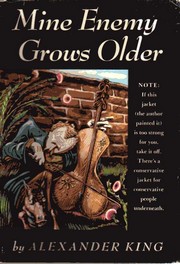

Simon and Schuster were happy to exploit this sense of dabbling in forbidden fruit. After “The Tonight Show” appearance, the publisher released subsequent printings with two covers–a “shocking” one (above) featuring one King’s Dali-esque paintings and, to prevent any awkward glances, a conventional one (right) with a safe grey cover.

King still has a few fans, as you can see from the reviews posted on Amazon. For me, his books, like his art, is colorful, vivid, but ultimately superficial.

Other Opinions

- • Gerald Frank, New York Herald Tribune, 7 December 1958

- This is a scandalous, wonderful, and strangely moving book. The publishers, for want of a better word, describe it as an autobiography. Actually it is less autobiography than memoirs, less memoirs than a series of immpressionistic self-portraits and wildly hilarious anecdotes done so vividly that the book all but leaps in your hands.

- • Bernard Levin, The Spectator, 4 December 1959

- Alas, funny though the anecdotes, or some of them, are, this is the emptiest book to appear for many a year, and even if it were not written almost entirely in the same breathless, sweaty prose, it would still be a waste.

- • Raymond Holden, New York Times, 4 January 1959

- The reader who has a strong stomach and is not irritated by the author’s verbal juggling and sometimes painful name-calling will be made either happy or morbidly excited…. [T]here are sandwiched in between its horrors some anecdotes and personal narratives of rare subtlety and humor. Whether one regards this as autobiography or fiction (the two are not really so far apart), it is at once a story of degradation and depravity and a sensitive and often kindly commentary on human life.

Locate a Copy

- Look for it at Amazon.com: Mine Enemy Grows Older

- Look for it at Amazon.co.uk: Mine Enemy Grows Older

- Look for it at AddAll.com: Mine Enemy Grows Older