“Once a bear kept a small inn for animals. Not many, just a mole or so, a chipmunk, a cat, several birds, a sheep and a deer. Wasps and bees, also inhabitants, didn’t count because they were innumerable.” Jean Garrigue’s 1966 novella, The Animal Hotel seems at first to be just a charming children’s story. The bear is a marvelous host, a diligent housekeeper who reminds the cat to keep its fish heads in a neat pile and the deer not to leave a trail of grass in the living room. She fixes wonderful meals of seeds and berries and each night they entertain each other with stories.

During the day, they wander through the fields and forest nearby, “traveling the way a brook does, by the path of least resistance”:

True enough, it took them like the brook longer to get wherever they wanted to go, but again, what of it? Every brook may feel that its destiny magically and magnetically draws it to some distant river but does the attraction of that looming end oblige it to get there by that shortest distance, a straight line? No. The sense of other destiny is there all the way, in every flat or round stone the brook trips over, under every bush, tree or moss-ledged wall the brook passes by, and so it was with these beasts when they went out on their rambles. Every moment of divaricating, very desultory direction they took was as significant to them, as bewitching and surprising as whatever it was they thought would be awaiting them.

But soon the simple tale of the happy life led by this rag-tag clan reveals a deeper layer underneath. There a loneliness in the bear unlike the other animals. The mole was blind, “didn’t care and had never known better.” But the bear “seemed to have renounced society.”

When hoof prints appear in the forest, the animals grow concerned. Too big, too nervous, too powerful to be trusted in their household. The bear goes out to look for him, so shoo him off. But then she stays away most of the day and then she disappears entirely. Each beast begins to feel “that the great days were over and their queen gone,” and to wonder if it is now time to move on.

Then, “after days and days, a very little packet of eternity,” she returns. Bedraggled, thin, with a thick leather collar around her neck and a chain dangling from the collar. The animals brew up a pot of tea and set to nursing her back to health.

When she recovers, she tells the animals not just of how she fell in love with the horse and went with him to the land of men but of the great career she had had many years before, performing in the greatest of circuses with another horse. And just as she had escaped from the circus to build a refuge deep in the forest, so she fled again this second time. Their special world restored to the animal hotel, they can look forward to the good times going on and on and on. “Would they not go on, and forever?”

At just under 100 pages and published by a small and then-new New York firm, the Eakins Press, The Animal Hotel went virtually unnoticed. In one of its very few reviews, Denis Donoghue wrote in The New York Review of Books that Garrigue’s writing had “a Book of Hours simplicity”:

Something of this quality is audible in The Animal Hotel. But the most important thing is that she knows her powers, she knows what she can do. If you want to write fabulous prose, the best bet is to compose a fable; to get the genre right before trying to get everything else right. Miss Garrigue has done this. So she is free to turn her pretty phrases, to speak of “the curl and curlycue of her voice,” giving the language its head: “Not me, I replied, for I saw what I knew and knew what I had to do and threw up the cards, every one, all the trumps of them and the trumpets, the trumpery too, and the triumphs.”

This is Miss Garrigue’s way of restoring the magic, by writing a book of charms, making the sentences charming.

In a short memoir of the early days of the Paris Review, George Plimpton claimed that The Animal Hotel was inspired by Garrigue’s experiences living at the Hotel Helvétia and its proprietors, Monsieur and Madame Jordan, who were generous and understanding hosts. Garrigue strung a clothesline across her room to allow a group of finches to reside with her. Not surprisingly, when Plimpton was offered to take the room over after she’d left, he found it “filled with sticks, stones, moss, seeds, wings, thistles, parts of dandelions, parts of pigeon’s eggs and snail whorls, etc.”

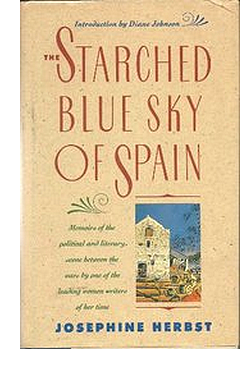

Elinor Langer provides the explanation in her superb biography, Josephine Herbst: The Story She Could Never Tell (1984):

When I think of Josie as she was in her later years — or rather, as she appeared — I see a vital woman surrounded by a circle of eager admirers, somewhat after the manner of the classic fairy tale in which a maternal figure has taken shelter deep in the heart of an enchanted forest surrounded by swarms of little people on whom she is really dependent but who are also under her spell. In the story the unorthodox household is occasionally menaced — someone is wounded or lost or word drifts in on the lips of animals about trouble in neighboring territories or from remnants of the past — but on the whole it is a safe and sufficient unit, mysteriously enveloped in a kind of protective charm. There actually was such a fable written about Erwinna, by Jean, a prose novella, The Animal Hotel, first published in the periodical New World Writing in 1956. The saga of a country lodging run by an amiable but elusive Bear whose “past was more complicated than anybody could guess” had its origin, more or less, in fact, for as the 1950s progressed, the house in Erwinna was becoming a stopping place for a group of young men and women just beginning to make their marks on the world, and Josie was very much the star…. Through their eyes the idea of Erwinna as a place of fellowship and creativity not just aloof from but superior to the world’s demands was magically reborn.

One of these young women, Jane Mayhall, later wrote that Herbst “made one feel that life was a kind of involved continuity”: “Reassurances and advisos toward attention to immediate events.” But like Garrigue’s bear, “she did suggest that there were realities beyond the moment.” As Langer shows, one of Herbst’s painful realities was Garrigue’s constant affairs and dalliances with other women and men, which by the time The Animal Hotel was published had left her lonely and forgotten.

Josephine Herbst died of cancer in early 1969; Jean Garrigue died of Hodgkin’s disease almost exactly three years later. In her last collection of poems, Studies for an Actress and Other Poems, Garrigue included a tribute to Herbst in a poem entitled, “In Memory”:

You did not doubt that you were beloved

And by good strangers, friends to you

Bearing the promised language.

Yet skeptic you could doubt

Out of a full heart

Who tried to beat the gameAnd did so, again, again,

And raised us leaves of hope by that

For something simple like a natural thing,

for something large, essential, driving hard

Against the stupors of too much gone wrong.

And by your intensity

Of flame against the dark

(You beat up flame,

You beat it up against the dark)Gave us greater want

To change the heart to change the life

Changing our lives in the light that is changing

But which has no future, no yesterday.

Technically, The Animal Hotel has never been out of print and you can still order a new copy from the publisher, Eakins Press.