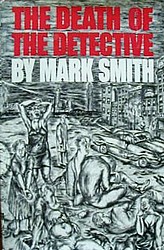

Northwestern University Press this month reissued Mark Smith’s The Death of the Detective, a novel considered by some of the readers who’ve discovered it since it went out of print nearly 25 years ago to be one of the greatest works of American fiction of the 20th century. Although nominated for a National Book Award when first published in 1974, its critical reception was, on the whole, mixed. The New York Times Book Review said of it,

[Smith’s] large and eccentric melodrama is marked by lavish skill at doing what novelists always need to do–write scenes, weave narrative threads, hatch and construct characters, see and smell and feel and describe. Good sentence piles upon good sentence until the novel sags and cracks. What it sorely needs is a blue pencil and an artistic point of view.

Its status hasn’t improved much over the years. One of its Amazon reviewers gave it five stars and the tag-line, “Ross MacDonald meets (the american) John Gardner,” and this is as apt a summary as any. Like Gardner’s magnum opus, Nickel Mountain (now out of print), The Death of the Detective is ambitious, grand in scope, and overloaded with atmosphere, moods, and characters. Novelist Wallace Markfield slammed Smith (getting his name wrong) and Gardner in one swat in a 1978 interview available online at the

Markfield: There’s a stench given off by novels written by academics. A point in case is John Gardner. It’s a stench of unreality. There is no contact between Gardner and the real world. He’s fanciful and he has a few pathetic tricks. Another case in point is an academic named Frank Smith; he wrote something called The Death of the Detective

Interviewer: I don’t know it.

Markfield: You’re not missing very much. I read it and why I finished it I don’t know. It was a terribly boring book. You know, clearly modeled upon whomever. But of no interest whatsoever in the world.

The Death of the Detective is one of the books that inspired me to start this site and has been one of my Editor’s Choices since day one. While I can see the point of the New York Times critic who wrote that it could stand some “blue pencil” editing to trim off some of its excess and improve its artistic merit, I don’t think artistic merit is the reason to seek out and read this book. The Death of the Detective is a book about Chicago, and like that city, prone on occasion to extremes of temperature, drama, and violence, which is what makes it such an engrossing and memorable reading experience. It’s the novelistic counterpart to Sandburg’s “Chicago”:

They tell me you are wicked and I believe them, for I have seen your painted women under the gas lamps luring the farm boys.

And they tell me you are crooked and I answer: Yes, it is true I have seen the gunman kill and go free to kill again.

And they tell me you are brutal and my reply is: On the faces of women and children I have seen the marks of wanton hunger.

And having answered so I turn once more to those who sneer at this my city, and I give them back the sneer and say to them:

Come and show me another city with lifted head singing so proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning.

If it were ever made into a movie, its settings would be dark, its lighting melodramatic, and its score heavy with pipe organ chords, and you’d sit there in the theater, reveling in the sensory overload. But why wait for the movie? Find a copy, crack open its covers, and dive in. You will surface a few days later — perhaps a bit drained, but in awe of Smith’s ability to achieve sensory overload with nothing more than words on a page.

Cars splashed through the colors, took and bent the letters momentarily on their trunks and hoods. Pedestrians who crossed the street stepped into an O, waded through a P, took the colors on their rubbers and domes of their umbrellas. Like spilled gasoline, streaks of color ran in the flooded streets. Inside the Scarponi stores, which were the size of supermarkets and like great technicolor billboards set out against the night, drowsy clerks stood in the aisles between the shelves of bottles and lines of empty grocery carts with their arms folded across their chests, or they leaned upon the counters by the cash registers, pencils tucked behind their ears, staring out through the downpour that rolled down the plate-glass window at the bedraggled, floundering, pedestrians and the creep and glitter of the traffic in the streets.

Cars splashed through the colors, took and bent the letters momentarily on their trunks and hoods. Pedestrians who crossed the street stepped into an O, waded through a P, took the colors on their rubbers and domes of their umbrellas. Like spilled gasoline, streaks of color ran in the flooded streets. Inside the Scarponi stores, which were the size of supermarkets and like great technicolor billboards set out against the night, drowsy clerks stood in the aisles between the shelves of bottles and lines of empty grocery carts with their arms folded across their chests, or they leaned upon the counters by the cash registers, pencils tucked behind their ears, staring out through the downpour that rolled down the plate-glass window at the bedraggled, floundering, pedestrians and the creep and glitter of the traffic in the streets.