Long before Clifford Irving concocted his fake autobiography of recluse millionaire Howard Hughes, mock autobiographies have been a popular vehicle for satire — usually of the sort of people who wrote these books, less frequently (viz. Roy Lewis’s The Evolution Man), of the (real, not mock) author’s contemporaries. I’ve written about a number of these over the years, but I had no idea how broad this seemingly narrow sub-genre was until I started compiling this list, which is less comprehensive than I suspected a few days ago. And so, in no particular order, here is a baker’s dozen of autobiographies (and diaries) that are not — Surprise! — by the people they claim to be.

- • My Royal Past (1940, revised 1961)

- By Baroness von Bülop, nee Princess Theodora Louise Alexina Ludmilla Sophie von Eckermann-Waldstein. Actually by Cecil Beaton.

- Perhaps the ultimate proof of the fact that Cecil Beaton felt his position as preferred photographer to the Court of St. James secure was the fact that not once, but twice, he mocked both his subjects and his own staid style of photographing them in this illustrated memoir of a remote offshoot of the tangle of Saxe-Coburg-Hesse-Hohenzollern-Hapsburg-etc. bloodlines that ruled Europe for too bloody long. Beaton himself dressed up as the Baroness, accompanied by such friends as the cartoonist Osbert Lancaster, all dressed up in gowns and bemedalled uniforms.

- Beaton was so sure of himself, in fact, that he provided his own review blurbs before they were written: e.g., “Here, as Lord Beaconsfield said, is a book that no time should be wasted in reading.” Perhaps to capitalize on his renewed fame for his costume designs for the Broadway musical My Fair Lady, My Royal Past was revised and reissued in 1961, including this time a list of errata, such as . And as one accustomed to paying attention to details, Beaton was sure to include a detailed index with such entries as:

Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s entries in the index to My Royal Past. - • Quail in Aspic (1962)

- By Count Charles Korsetz. Actually by Cecil Beaton

- Beaton had such fun with My Royal Past that he took another shot at the sub-genre the year after its reissue. Quail in Aspic was an “as told to” autobiography of a Hungarian count who had a knack for being on the side of European noble houses moments before their demise. He manages to remake himself as a proper English gentleman, however, complete with a fine country house and a matching set of prejudices.

- This time around, Beaton recruited his long-time friend, the society hostess Elsa Maxwell, to portray the Count in the photographs (by Beaton, of course) that illustrate the book.

- • Cyril Pure’s Diary (1981)

- By Cyril Pure. Actually by Michael Geare.

- Cyril Pure is a man after every bookshop owner’s heart. Of malice, that is. Set up in Chipping Toad’s only bookshop, he dives headlong into the bookselling industry. Although it might be more accurate to say that the UK’s bookselling industry dives headlong upon him, rather like a pack of ravenous vultures. One publisher’s rep, having heard the shop has sold one of their books, leaves Cyril with 100 copies of a sure bestseller, Reminiscences of an Old Crocodile Shikari. The Chipping Toad Poetry Society names him its Vice President, in return for which he has the honor of hosting a reading by the famous Cement poet, Bert Stunge, and providing refreshments. Cyril puzzles over the inner meanings of Stunge’s work:

- Geare teamed up with Michael Corby the following year to write another mock diary, this time of the famed Transylvanian count, who, as it turns out, spent quite a lot of time in Victorian England, attending Balliol and Oxford, exchanging ripostes with Oscar Wilde, meeting Sherlock Holmes, and implicating Van Helsing in the Jack the Ripper murders. It’s earnest fun but more earnest than fun, unfortunately.

- • Lord Bellinger (1911)

- By Lord Bellinger. Actually by Harry Graham.

- Although just one generation away from trade, Lord Bellinger has easily adapted to the life of the idle nobility, priding himself on being “naturally disinclined to anything approaching effort.” An early attempt at portraying the type of privileged dimwit parodied in Monty Python’s “Upper-Class Twit of the Year” competition and now occupying numerous junior minister positions in the current Conservative government, Harry Graham ultimately missing his mark by favoring kindness over brutality in his approach.

- I wrote about Lord Bellinger back in 2013.

- • Little Me: the intimate memoirs of that great star of stage, screen, and television, Belle Poitrine (1961)

- By Belle Poitrine (see above for the rest). Actually by Patrick Dennis.

- Dennis, rocketed to fame and fortune with his novel Auntie Mame and its Broadway and film adaptations, may have had most fun with this account of the successes, failures, and romantic entanglements of a grand dame actress a la Tallulah Bankhead, Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, etc. Dedicated to her four husbands, including the fourth and shortest-lived (literally), Letch Feeley, the former Pomona gas station attendant who had the misfortune to step onto a yacht with his mistress just moments before it quite unexpectedly exploded. Illustrated with photographs by Cris Alexander.

- Like Beaton, Dennis enjoyed this form so much that he followed a few years later with First Lady (1964), the memoirs of Martha Dinwiddie Butterfield, whose husband, George Washington Butterfield, occupied the White House for 30 days in 1909 — most of that time drunk or cavorting with his mistress, Gladys Goldfoil, in one of the spare bedrooms.

- • I Think I Remember (1927)

- By Sir Wickham Woolicomb (“ordinary English snob and gentleman”). Actually by Magdalen King Hall

- A celebration of a life lived “when gentlemen were gentleman” and before “all this socialism, etc., made everything cheap and nasty.” As with Lord Bellinger, it’s easiest to simply poke fun at the pompous than to turn parody into an authentic comic creation. As The New York Times‘s reviewer put it, “In parodying the pompous tomes of reminiscences that great personages manage to foist on the publishers and public with little difficulty, Miss King-Hall has taken a step downstairs. It is as if James Joyce, after completing A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man had gone ahead to fashion A Portrait of an Old Man with Senile Dementia.”

- There must be something about these spoofs that inspires certain authors. Magdalen King-Hall wrote two others: The Diary of a Young Lady of Fashion in the Year 1764-1765 (1926), which mocked the pretences and rituals of Georgian England and which she admitted she’d only written to escape the boredom of a summer at the English seaside; and Gay Crusaders (1934), the memoir of an English knight in the Third Crusade, an experience enlivened by liberal amounts of booty and made tiresome by the consistent habit of the French to arrival after all the fighting was done.

- • Water on the Brain (1933)

- By Major Arthur Blenkinsop, formerly of the Boundary Commission in Mendacia. Actually by Compton Mackenzie

- Mackenzie, who ran a British intelligence and special operations network in Greece during World War One and was involved in everything from the disastrous Gallipoli campaign to an attempted assassination of Prince Phillip’s father, then King of Greece. Somewhat resentful at his lack of recognition from his higher ups, Mackenzie wrote this account of one particularly inept and dull-witted agent recruited into the service of His Majesty’s Director of Extraordinary Intelligence, MQ99(E).

- • The Way Up (1972)

- By Anaxagoras, Duc de Gramont. Actually by Sanche de Gramont (who later changed his name to Ted Morgan).

- The Way Up may have been an attempt to cash in on the success of the first of George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman series, mock memoirs by Harry Flashman, the villain of Thomas Hughes’s earnest Victorian boy’s novel about Rugby, Tom Brown’s School Days. In De Gramont’s case, his villainous hero is a fringe member of the court of King Louis XV, adventurer, soldier of fortune, slave trader, and courtier. Ironically, however, it was Scotsman Fraser who demonstrated a greater talent for panache than his French wannabe competitor. De Gramont/Morgan stuffs almost 500 pages full of plot but failed to come close to the joyous sense of bastardry that makes the Flashman novels so much fun.

- • The Autobiography of Ethel Firebrace (1937)

- By Ethel Firebrace. Actually by Gay Taylor and Malachi Whitaker.

- The Victorian novelist par excellence, Ethel Firebrace wears out four typewriters churning out over a hundred novels or over five million self-righteous words. By her own account, Ethel is not a prig. It simply happens to be the fact that everyone else is lazy, ill-mannered, and untrustworthy.

- And non-garglers. Ethel attributes her success (“or very nearly all of it!”) to her habit of gargling after food. Writers who fail to gargle “spring up like toadstools, live as long, and disappear as ignominiously.” Needless to say, but “there are no garglers among modern poets.”

- As I wrote back in 2019, The Autobiography of Ethel Firebrace was a jeux d’esprit for lifelong friends Taylor and Whitaker, but on the whole probably more fun for them than us.

- • The Autobiography of Augustus Carp

- By Augustus Carp, Esq. Actually by Henry H. Bashford.

- Most of these books are amusing. Some are laugh-out-loud funny. The Autobiography of Augustus Carp is a comic masterpiece. Bashford, a Harley Street physician and amateur writer, grasped something that many of his fellow mock autobiographers failed to: namely, that one cannot spoof half-heartedly. There are moments, for example, when the reader sees the props in a book like The Autobiography of Ethel Firebrace, sees the scene being staged for a joke at Ethel’s expense. Bashford, on the other hand, understood that Augustus Carp is not only blissfully unaware of his ridiculousness but absolutely convinced of his constant and superior moral rectitude. And so, for example, if he happens to get hammered by imbibing excessively of a drink he’s told is “Portugalade,” he is not just a drunken boor but completely ignorant of the fact that he’s drunk. There’s a certain giddy delight in observing how often Bashford is able to coax Augustus into behaving like an idiot without his gaining the slightest clue to what’s going on.

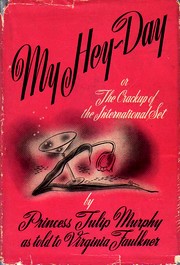

- • My Hey-Day: The Crackup of the International Set (1940)

- By Princess Tulip Murphy. Actually by Virginia Faulkner.

- Taken from a series of articles Faulkner wrote for Town and Country in the 1930s, My Hey-Day is a world tour in the company of Tulip Murphy, former good-time girl and widow of “Brick-a-Minute” Murphy, who claimed to be related to ancient Irish royalty in some unspecified way. Unspecified is all right with Tulip, who’se never seen a set she couldn’t force her way into. Whether she’s visiting Scandanavian, the Soviet Union, France, Tibet, or Hollywood, Princess Tulip manages to mock power, wealth, class, culture, sexuality, and, most of all, fashion. No matter how limited her purse, she finds some old thing to throw on:

- Princess Tulip noted, with regret, that the onset of World War Two was curtailing the activities of the International Set: “Many of my oldest friends can now count their yachts on the fingers of a single hand.” However, Faulkner carried Tulip through at least a dozen more adventures after My Hey-Day was published, visiting New Orleans, Washington, Mexico, a Western dude ranch, and the wedding of Rita Hayworth and Aly Khan in 1949 and setting at least the American land speed record for gate crashing.

Tring, tring

Shoestring, heating

Bloating, fourteen

Umpteen, thumping…

I was wearing an original Déclassé (salvaged from the wreck of my wardrobe), of spaghetti-colored cambric, handsomely trimmed in gum-drop green duvetyn with shoulder-knots of solid tinsel. My hat was a saucy beret no bigger than an aspirin tablet, which was held to my head by a specially trained family of matching chameleons. My only jewelry, square-cut cultured emerald cufflinks, matched the duvetyn, and I carried a fish-net parasol which also could be used for water-divining.