Earlier this year, the Daily Telegraph published a piece by Charles Moore on Miklos Banffy’s Transylvanian Trilogy, or, as the author referred to it, “The Writing on the Wall.” Over the course of the last ten years, mostly through word-of-mouth recommendations, these three novels–They Were Counted, They Were Found Wanting

, and They Were Divided

–originally published in Hungary between 1934 and 1940, have become recognized by a small but enthusiastic band of readers as one of the finest works of the 20th century.

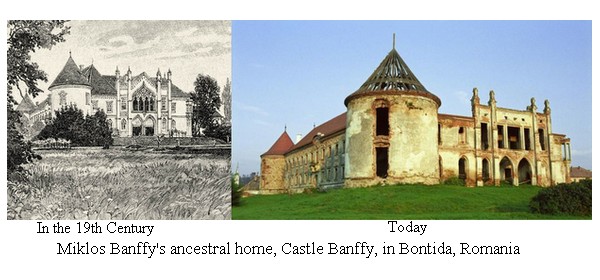

Banffy, or, to use his full title, Count Miklos Banffy de Losoncz, was a member of the Hungarian nobility and a liberal politician, influential in the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and an early foreign minister of Hungary after the ouster of Bela Kun’s communist regime in 1920. After retiring from that office over differences with the Regent, Miklos Horthy and the ruling conservatives, Banffy retired to his ancestral home, Bontida Banffy Castle, in Transylvania–in an area now part of Romania.

Banffy, or, to use his full title, Count Miklos Banffy de Losoncz, was a member of the Hungarian nobility and a liberal politician, influential in the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and an early foreign minister of Hungary after the ouster of Bela Kun’s communist regime in 1920. After retiring from that office over differences with the Regent, Miklos Horthy and the ruling conservatives, Banffy retired to his ancestral home, Bontida Banffy Castle, in Transylvania–in an area now part of Romania.

Not only did Banffy’s politics run counter to most of the Hungarian establishment, but soon after his trilogy was first published, his country had the misfortune of falling under the control of the Nazis and then the Soviets. That Banffy’s last venture into diplomacy was an attempt to persuade Romania and Hungary to break with Germany and take sides with the Allies did not help. As reader Malcolm G. Hill wrote in a fascinating comment on Moore’s piece in the Telegraph,

About a year after having read them I travelled by motorhome through all the areas in Transylvania mentioned in the trilogy, now part of Romania, with the aid of a map giving the original Transylvanian names of the towns and villages which had been changed into Romanian. The saddest place to visit of all locations directly connected with the book was the Banffy Castle at Bonchida, Bontida in Romanian, some 30k to the north of Kolozsvár(now Cluj Napoca) the one-time home of the Banffy dynasty and which doubles as Balint’s country estate home of Denestornya in the trilogy. The ruination of this once gorgeous country house which Banffy never tires of lovingly describing in so many parts of his epic novel is a terrible tragedy, brought about solely due to its wanton and deliberate destruction as an act of spiteful vengeance by the retreating German forces in WWII owing to Banffy’s part in negotiating Hungary’s withdrawal of support for Germany towards the end of the war. The Germans not only left the castle a smoking ruin but destroyed all its furniture and paintings as well as Banffy’s priceless library and family archives. The present Romanian government is endeavouring to restore some parts of the castle complex that were least damaged but it seems a forlorn task to me.

Even within his own country, his books were viewed unfavorably by both regimes and fell out of print for over thirty years. It was not until 1982 that the books returned to print. Patrick Thursfield first brought the work to the attention of English-speaking readers in the Contemporary Review in 1995. As he summarized the story then, “The three books of the trilogy cover ten years in the life of one Count Balint Abady, like the author, a Transylvanian aristocrat, landowner and high-profile politician and, parallel to his story, the sad tale of the wasted life and degradation of Abady’s first cousin, the talented but hopeless Count Laszlo Gyeroffy.”

Banffy took his titles from God’s condemnation of Belshazzar, the last king of Babylon. As written in the Book of Daniel,

But thou hast lifted up thyself against the Lord of heaven; and they have brought the vessels of his house before thee, and thou, and thy lords, thy wives, and thy concubines, have drunk wine in them; and thou hast praised the gods of silver, and gold, of brass, iron, wood, and stone, which see not, nor hear, nor know: and the God in whose hand thy breath is, and whose are all thy ways, hast thou not glorified: Then was the part of the hand sent from him; and this writing was written.

And this is the writing that was written, MENE, MENE, TEKEL, UPHARSIN. This is the interpretation of the thing: MENE; God hath numbered thy kingdom, and finished it. TEKEL; Thou art weighed in the balances, and art found wanting. PERES; Thy kingdom is divided, and given to the Medes and Persians.

As the New Statesman review of They Were Counted put it, “The ‘they’ in question is Hungary’s ruling class, who drink, dance, quarrel and gamble their way into the disasters of this century as unprepared as Belshazzar himself.” Or, as Banffy himself wrote in They Were Counted,

As far as most of the upper classes were concerned, politics were of little importance, for there were plenty of other things that interested them more. There were, for instance, the spring racing season, partridge shooting in the late summer, deer-culling in September and pheasant shoots as winter approached. It was, of course, necessary to know when Parliament was to assemble, when important party meetings were to take place or which day had been set aside for the annual general meeting of the Casino, for these days would not be available for such essential events as race-meetings or grand social receptions.

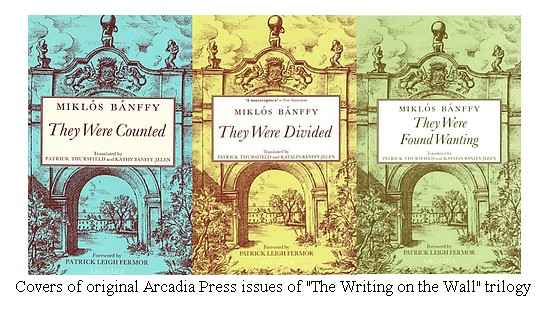

Thursfield located Banffy’s daughter, Katalin Banffy-Jelen, and together they worked for several years in the late 1990s to translate the mammoth work–over 1500 pages long–into English. The books were then published by a small U. K. publisher, Arcadia Books, between 1999 and 2001.

Thursfield and Banffy-Jelen worked hard to convey the intricacies of Hungarian politics and culture to an audience separated by decades and a general ignorance of Banffy’s settings aside from paprika and Dracula. Their effort was remarkably successful, earning them the 2002 Oxford-Weidenfeld Prize for translation.

Each of the books received highly positive reviews in the major U. K. newspapers. Ruth Pavey wrote in the Independent: “This is the sort of book that is hard to finish: not in the sense of getting through because, despite its length, that’s easy. Rather, it’s because The Transylvanian Trilogy is so successful in recreating its lost world – a world which after turning the last page, the reader, too, must leave behind.” The Scotsman’s reviewer exulted,

[Th]is is a novel of great events and the private lives of a huge cast of characters told with gusto and amplitude…. If it is the Romantic elements that make the novel so enjoyable, so irresistible, it is the author’s keen political intelligence and refusal to indulge in self-deception which give it an unusual distinction. It’s a novel that, read at the gallop for sheer enjoyment, is likely to carry you along. But many will want to return to it for a second, slower reading, to savour its subtleties and relish the author’s intelligence.

Jan Morris named They Were Found Wanting as one of her books of the year for 2000 and Caroline Moor wrote in another year-end wrap-up, “My great find of the year is a reprint of the magnificent trilogy, set in pre-war Transylvania by Miklos Banffy–which stands comparison with the great Russian and French masters. Banffy vies with Tolstoy for sweep, Pasternak for romance and Turgenev for evocation of nature; his fiction is packed with irresistible social detail and crammed with superb characters: it is gloriously, addictively, compulsively readable.” More recently, the playwright John Guare called the work, “… revelatory … the fastest 1,700 pages you’ll ever read.”

Despite the praise, however, the books remained difficult to locate and it appears that Arcadia did not reprint them after their initial runs. Thursfield died in Tangier on 22 August 2003, a few months short of his 80th birthday. A few readers managed to find copies, though, and keep the grapevine pulsing in the work’s favor. In 2007, Michael Henderson proclaimed it “A masterpiece in any language” in the Telegraph: “… please give this civilised Hungarian a go. Ignore the tyranny of approved lists, and those breathless claims made on behalf of novelists said to be ‘at the height of their powers.’ Plunge instead into the cleansing waters of a rediscovered masterpiece, because The Writing on the Wall is certainly a masterpiece, in any language. And if, having read it, you feel let down, I shall provide reimbursement.”

Luckily, Arcadia began bringing The Writing on the Wall back to print in 2009. They Were Counted and They Were Found Wanting

are available now (at least in the U. K.) with new covers a slightly more likely to attract readers, and They Were Divided

will be re-released in October 2010. The original Arcadia covers, by the way, featured a drawing of the entrance to Bontida Banffy Castle from the mid-19th century. Blogger Andrew Cusack celebrated their resurrection earlier this year, writing of the novels, “Three volumes of nearly one-and-a-half thousand pages put together, they make for deeply, deeply rewarding reading, transporting you to the world that ended with the crack of an assassin’s bullet in Sarajevo, 1914.” And Charles Moore, as mentioned at the start of this piece, acclaimed in the Telegraph: “This growing acclaim is deserved. Banffy’s trilogy is just about as good as any fiction I have ever read…. Although they are very funny, they are deeply serious. They are like Anna Karenina and War and Peace rolled into one. Love, sex, town, country, money, power, beauty, and the pathos of a society which cannot prevent its own destruction–all are here.”

So what are you waiting for?

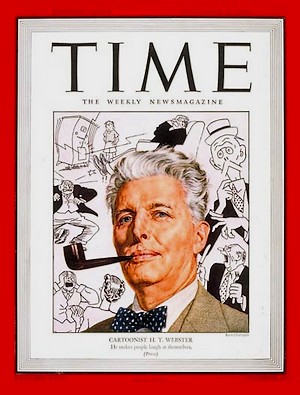

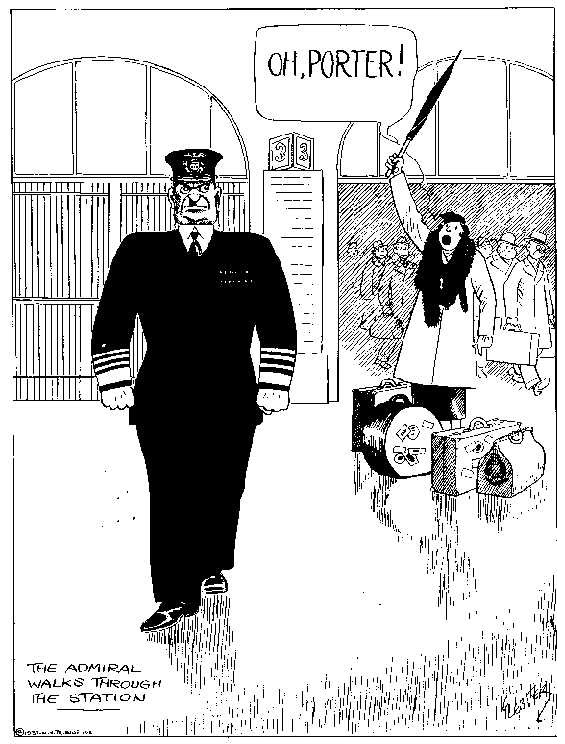

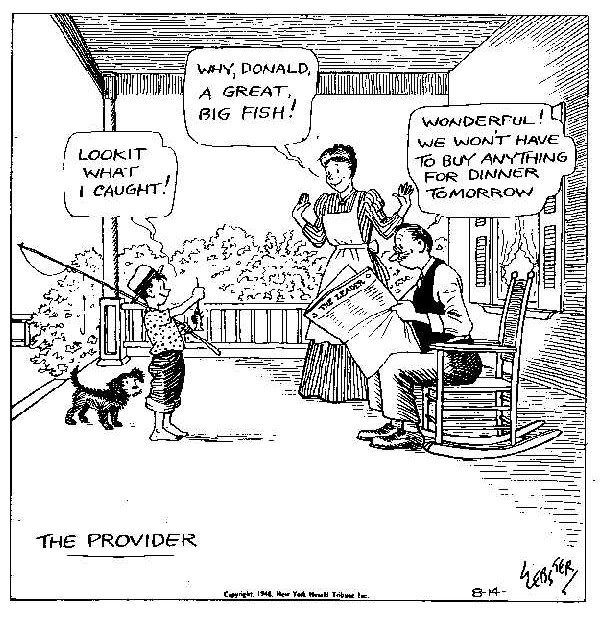

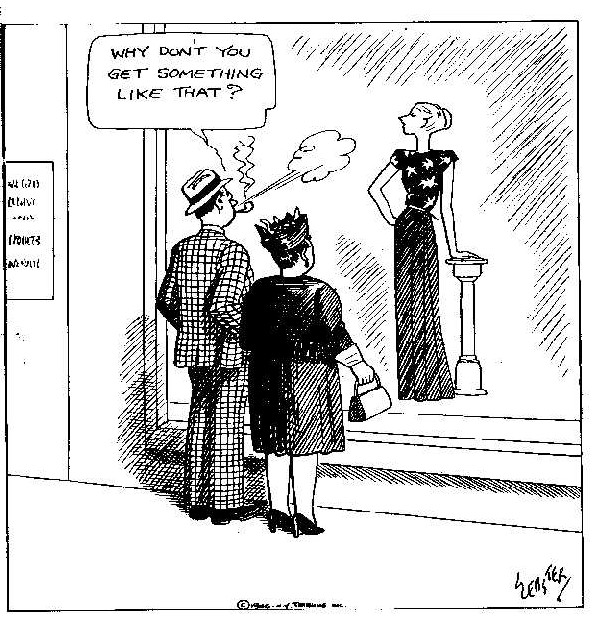

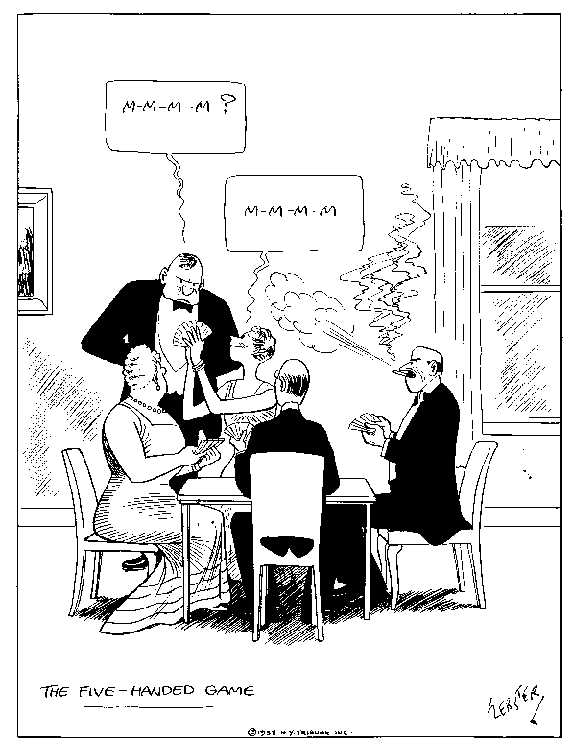

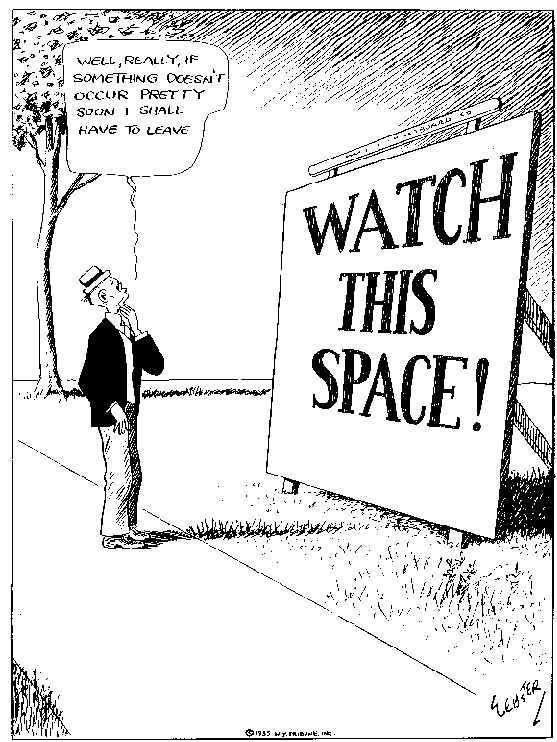

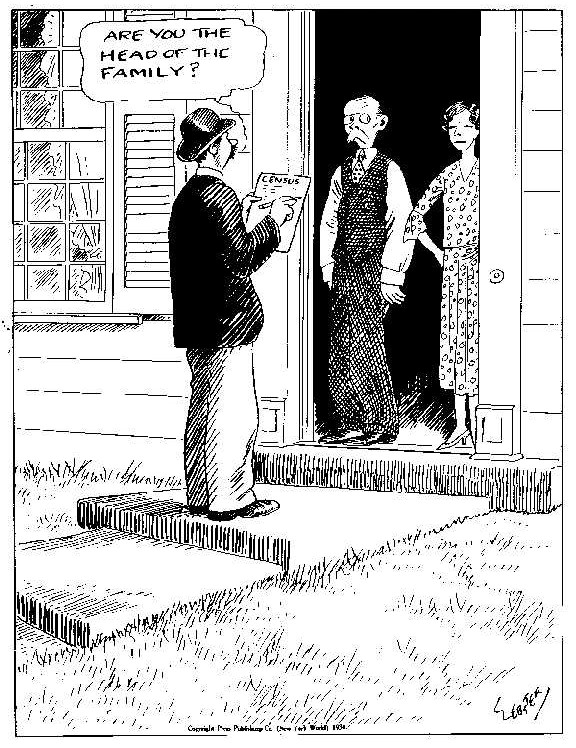

Webster published over 15,000 panels over the course of 40-plus years as a newspaper cartoonist. A memorial collection of his cartoons,

Webster published over 15,000 panels over the course of 40-plus years as a newspaper cartoonist. A memorial collection of his cartoons,

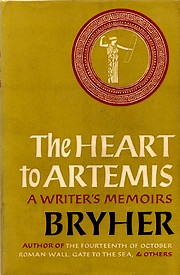

dreamed about Bokhara, a fabulous city that was then more difficult to access than Tibet. I opened my eyes upon the end of not only the nineteenth century but of a second Puritan age. An epoch passed away while I was learning to speak and walk. Its influence remains as the start of memory and as a measuring rod for progress that even Edwardian survivors lack.

dreamed about Bokhara, a fabulous city that was then more difficult to access than Tibet. I opened my eyes upon the end of not only the nineteenth century but of a second Puritan age. An epoch passed away while I was learning to speak and walk. Its influence remains as the start of memory and as a measuring rod for progress that even Edwardian survivors lack. I couldn’t resist starting in with the most ridiculous title in the bunch:

I couldn’t resist starting in with the most ridiculous title in the bunch:  Donald Schon’s

Donald Schon’s