“The Passing of Pengelley”, by James H. Williams

“The Passing of Pengelley”, by James H. Williams

from Blow the Man Down!A Yankee Seaman’s Adventures Under Sail , by James H. Williams and edited by Warren F. Kuehl

, by James H. Williams and edited by Warren F. Kuehl

First published in Seafarer and Marine Pictorial, II (February 1922)

We lay three months in the port of New York discharging and loading cargo and repairing the hull and rigging of the Late Commander before we sailed again for Calcutta in May of 1887. Two months later, on the fifteenth of July—midwinter in the Southern Ocean—we rounded the boisterous Cape of Good Hope and began circling boldly away toward the forty-sixth parallel to begin running our easting down.

A week later, we were in the midst of our great easterly sweep toward the eighty- fifth meridian. The prevailing westerly winds peculiar to the zone had gradually increased in force and the sea had risen, so that now we were scudding through the tumult and smother of a mighty gale at a seventeen-knot gait. We were swinging three whole topgallant sails with preventer backstays set up and preventer braces on the cro’jack yards. Running with squared yards and everything bar taut, there was not much to do except relieve watches and stand by for emergencies.

For three consecutive days during this superb run, the old ship made a glorious record—over a thousand miles with five thousand tons of case oil as cargo in our hold. Here is an authentic sailing item for amateur sailors and deepwater yachtsmen to ponder over.

On the second day of that great run, we passed two British-Australian mail steamers. Both were high-diving until the crests of the seas threatened to flood their boiler rooms through the funnel tops. Their propellers churned wind oftener than water.

We were running with an old-fashioned log at that time—a canvas bag and a wooden plug trailed by a sticky line wound on a wobbly reel and held unsteadily aloft by a lurching seaman and timed by a sleepy apprentice with a worn-out sand glass. An honest taffrail log would have recorded us at least eighteen instead of the miserly fourteen-odd knots we were credited with. But sailors never were noted for doing anything remarkable except drinking rum and chewing tobacco.

On the third day of the big run, the wind had attained almost hurricane force, and the sea had risen to mountainous heights and fearsome aspect. Our grand old ship, however, carried on nobly and showed not the slightest symptoms of weakening or distress.

That night of Good Hope I shall never forget;

Ofttimes I look backward and think of it yet,-

We were plunging bows under, her courses all wet,

At the rate of fourteen, with to’gallan’ s’ils set.

So we’ll roll, roll, bullies,

Roll as we go,

For the kidapore ladies

Have got us in tow!

At four in the afternoon, before changing watches, the Old Man ordered the mate to take in the fore- and mizzen-topgallant sails since, as he declared, the ship was dragging instead of sailing. It had reached the limit of its sailing power, and the surplus canvas was now a hindrance rather than a help. As soon as ‘we had mustered watches, the order was given; clewlines, buntlines, and leechlines were manned fore and aft at the same time. In just twenty minutes, the two big kites were taken in and snugly stowed. The Late Commander carried a noble crew. As soon as we had the ship shortened down to a whole main-topgallant sail, the port watch was sent below and the watch on deck was left to clear up the tangle of loose gear washing about the deck and trailing overboard through the scuppers.

The ship continued her racing gait with no apparent slackening of speed after shortening sail, and she rode much easier and made better weather of howling winds and driving sea. When the starboard watch went below at four bells for the second dogwatch, the ship was high-diving and wallowing through the thundering seas at a terrific pace.

According to the common plan in British ships, the Late Commander’s forecastle was directly beneath the forecastle head, with two doors at one end, the hawsepipes at the other, and a massive patent windlass in the center. After our Act o’ Parliament supper of hardtack, “strike me blind,” and “water bewitched” had been disposed of, we lighted our pipes and gathered around the big windlass for our usual dogwatch smoke session and yarn-spinning contest.

We were a motley bunch of weather-beaten, hardened sailors, every mother’s son a typical man-Jack. Lords of the gale, we reveled in our manhood and our strength and knew no hardship except the misery and degradation of being too long ashore. The British element naturally predominated among us, not because the ship was British, but simply because the voyage had originated in England nearly four years before. All of the original crew had not yet been seduced into desertion by the crimps in the various ports. Still, the inevitable vacancies had had to be filled from time to time until now more than half of our foremast complement of twenty-two A.B.’s was non-British seamen. Only four of us, collectively known as the Yankee Squad, were native Americans.

Seated around the forecastle in various easy and careless attitudes, we were surely an uncouth and unearthly looking group that might have descended from some remote planet and been sent away into these desolate and uninhabitable solitudes where nothing but blowing whales and pinioned sea birds could find contentment or natural sustenance. All of us were fully clad in the height of the prevailing fashion—sea boots and pea jackets, with oilskins and sou’westers ready» on hand in case of an emergency call.

Ever since the mutiny at the Nore, a national superstition has prevailed in British ships, both naval and commercial, against striking seven bells in the second dogwatch and rigging the gangway out on the port side. When four bells terminates the first dogwatch at six P.M., the chimes begin with one bell again at six-thirty, two bells mark seven o’clock, and three bells are struck at seven-thirty. Then the usual intermediate one bell at a quarter to eight warns the watch below to turn out and get ready. The final stroke of eight bells ends the dogwatch and calls all hands on deck to muster at the mainmast.

It happened to be Saturday night, and just before three bells young Pengelley came splashing forward through the deck swash to visit the sailors. Pengelley was as welcome as a Christmas morning, for every man among us adored the big handsome young Cornishman. The entire watch arose as one man to greet him and offer him the place of honor in our midst as he pushed his way in. Of course, it was contrary to both rule and tradition for apprentices to associate in quarters with “common” sailors, but no one, not even old Cap’n Grummitt himself, ever thought of reprimanding Pengelley.

Like many other high-minded but hardheaded men, Pengelley’s father, being an officer in the Royal Navy, had insisted upon a sea career for his son even though the sensitive lad was unfitted by natural impulse and predilection for the hardships and drudgeries peculiar to the maritime service. Pengelley was a born scholar. He was studious, book-minded, and thoughtful rather than practical.

He was as much out of place among a windjammer’s crew as a marble statue in a farmer’s bamyard. Nevertheless, Pengelley was the light, the life, and the pride and ennobling influence of our whole ship’s company. We needed someone better, nobler, nearer the unknown unattainable than our miserable selves. That was why we all adored Pengelley. He never needed to do any sailorizing; we could do all that!

Politely but positively declining any of the vacated seats around the windlass, Pengelley stripped off his dripping oilskin coat and spread it over the horn of the windlass to drain. Then loosing his big woolen lammie at the throat, he stretched himself at full length in precarious comfort along the running board fronting the lower tier of bunks. The strait-laced restrictions of quarter-deck discipline evidently bored him, and he appreciated the homely good will and natural levity of us “common” sailors.

He seemed to be in unusually high spirits that night. His blue eyes twinkled with suppressed mirth and his chestnut hair glistened in the flickering light of the spluttering slush lamp. Although the constant lurching and diving of the ship rendered his recumbent position on the bunkboard somewhat insecure, Pengelley seemed to enjoy the situation. He began describing, with witty embellishments, some of the amusing mishaps to officers and crew which he had witnessed during the day.

The resonant clang of three warning strokes on the big watch bell directly over our heads interrupted his amusing recital and created an uneasy stir among the tired seamen. The short and comfortless dogwatch was nearing its close and we would soon be called on deck to wrestle with the warring elements again until midnight.

“Sing us a song, Pen, before the watch is called,” shouted Spike Riley. “Sumpin’ sad an’ sentimental; sumpin’ with a chorus so’s we kin all jine in an’ blow th’ wind. Ain’t no ladies present, ye know,” the old vagabond reminded us with an artful grin, “so we kin make all th’ noise we’ve min’ ter ‘ithout disturbin’ enybody’s nervous systim.”

“Let ’er go, Pen,” piped half a score of eager voices. “Order for a song! Go ahead, Pen. Sing ’er up.”

Always willing, Pengelley at once responded to our request. He broke into the opening verse of the sailors’ love song, “Anchor’s Weighed,” with all the entrancing vigor and glorious fervor of his marvelous voice. As verse after verse rolled out in perfect rhythm and soulful expression, the whole watch would take up the simple and appealing refrain with boisterous enthusiasm, our combined voices ringing and rising above the roar and thunder of the storm, the thousand deck noises, and the raging sea.

Our evening song ended in salvos of wild applause, and at the stroke of eight bells we donned our coats and hurried out on the deck. The night and the sea had assumed truly fearsome aspects. The heavy black wind bags that dominated the sky and shut out the light of heaven had settled over all apparent creation with appalling completeness. The night was as dark as a bottomless pit. Only the phosphorescent gleam of the breaking sea crests and the iridescent and fleeting glow of the splashing side wash afforded an occasional and flitting glimpse of the loom and tension of the bulging sails. The big westerly wind had settled down into a continual, monotonous, bellowing roar. The whitecaps were flecked angrily from the summits of the racing seas and lashed away in great windrows of gleaming spindrift that spread like driven snow flurries in the pathway of the rushing waves.

But everything on the ship held even though the storm seemed to have attained its maximum intensity. So, except for some untoward accident during the night, prospects seemed good that the ship would be able to carry on until morning.

When all hands had assembled at the main fife rail, Tom Splicer communicated the fact with the usual announcement, “Watch is aft, sir.” Then, after a brief interval of uneasy suspense, came the welcome, though slightly amended order and admonition: “Relieve the wheel and lookout. Two A.B.s at the wheel. That’ll do the watch. Stand by for a call.”

That the afterguard was feeling suspicious of the weather and preparing for trouble was quite evident, but it never pays to borrow trouble or spoil your peace of mind either by tragic anticipations or vain regrets. If we could read the inexorable decrees of fate beforehand, the human race would soon become extinct because every individual on earth would break his neck trying to dodge the inevitable.

As soon as the port watch had been relieved and gone below, the starboard watch scrambled for various safety perches above the level of the sea-swept deck. Most of the crowd climbed to the little flying bridge over the quarter-deck and wrapped themselves in the idle clew of the mizzen staysail, which had not been hoisted in over a week. The lookout was kept from the break of the poop, but as

I was the “farmer” that watch, having neither wheel nor lookout coming to me, I climbed to the top of the forward house and stowed myself snugly away beneath one of the big boats lashed keel upward to ringbolts in the beam skids. Lying down with my head pillowed on the oaken skid with only my sou’wester for softening, I soon fell sound asleep, entirely oblivious to all my wild and fear- some surroundings.

I was awakened from my slumber by hearing my name called in ordinary and friendly tone. Had it been a watch call, I should have scrambled out in a hurry and shouted, “Aye, aye, sir.” But as it was, I simply stretched out my hand, more provoked than alarmed, and felt a presence I could not see.

“Is that you, Pen?” I asked, sensing the identity of my unexpected visitor.

“Yes, it’s me, Jim,” answered the young apprentice. “Do you like manavlins? I gave the steward a shilling for the dog basket after supper last evening. The small stores are getting smaller now, and we don’t get much better food in the half deck than you men do in the forecastle.”

“I know it, you young rascal,” I answered as I sat up and eagerly accepted a generous section of sea pie proffered me in the dark.

After I had gobbled the cabin leavings, we sat together in shrouded silence beneath the pitch-black darkness of the upturned boat. Roundabout and overhead and down beneath us thundered the tumult of ship noises and the storm—-the rush and roar and hollow reverberations of driving seas; the monotonous, insistent wailing of the wind; the chaotic crash and tumult of an occasional comber breaching the rail, staggering the ship with its sudden impact and stupendous weight and battering the hatch coamings with the fury of a cataract. Overhead, the screaming tempest held high carnival in the vibrant shrouds. Idle chain gear rattled discordantly against the reechoing spars of hollow steel. The groaning yards and creaking blocks and grinding gins and singing boltropes told the terrific strain imposed upon our flawless gear.

Below the heavy deck, responding to every lurch, the throbbing hull labored incessantly beneath the avalanches of water constantly thundering aboard. The submerged clatter of disgorging sluice ports, the hollow chortling of choking scuppers, the occasional pounding of spare spars and loosened deck fittings kept apt and fitting accompaniment to the surrounding tumult. Above the storm, the wind reigned triumphant over all.

“What time is it, Pen?” I finally inquired.

“Six bells went before I came forward,” he replied. “Jones is keeping scuppers on the poop, and I’m standing by to call the watch. The second mate has been ordered to make one bell at half past and get all hands out. We’re going to take in the topgallant sail before the watch is relieved. It’s blowing harder now and we’re edging to the northward to get out of the zone and into smoother seas. “

“Well, Pen,” I said cheerfully, “I guess I’ll jump down into the forecastle and try a drag at the pipe before we start gehawking again. A feed like that deserves a smoke for consolation.”

“Wait a moment, Jim,” urged Pengelley in a pleading tone as he laid a restraining hand on my oilskins. “I want to ask a favor of you.”

“Sing out, Pen. It’s already granted,” I exclaimed, startled by the sudden tenseness and appealing solemnity of his voice. “What can I do for you?”

“Jim,” asked the young apprentice seriously, “do you remember the evening we first met in Calcutta?”

“Certainly,” I replied. “That was a year ago when all our squad went up to say goodbye to Black Harry and Piringee Katherine.”

“Yes, it was a year ago—just a year ago tonight. Do you remember that I told you it was the third anniversary of my apprenticeship?”

“Why, yes,” I answered. “I do. I suppose you are trying to remind me that tonight is your fourth anniversary in the half deck. Your indenture expires at midnight and tomorrow you will be eligible for promotion to the quarter deck. From Calcutta you will be sent to London to pass examination’ for your new rating. Congratulations, old man!”

I found Pengelley’s hand and gripped it warmly in the dark. For a moment neither of us spoke. Then he broke the tense silence beneath the sheltering boatwith a startling declaration.

“Jim, I am not going to reach Calcutta; I shall never see dear old England again.”

“Say, what ails you, Pen?” I exclaimed, horrified by his suddenly changed demeanor and mysterious talk. “You’ve been worrying about something and your wits are going astray. Tell me about it. You know I’m a safe counsellor and even if I can’t help you perhaps I can share the burden with you and help, you bear the strain.” I was so profoundly shocked by Pengelley’s behavior that I sat still in mystified silence waiting for him to proceed.

“Do you ever become frightened when you’re aloft, Jim?” asked the boy suddenly, gripping my oilskins nervously as he spoke.

“Scared, you mean? No, of course not,” I asserted contemptuously. “The safest place on a ship is aloft, especially on a night like this. You’re out of the deck smother, clear of the wrack, and above your officers for the time being. And the wind don’t blow any harder upstairs than it does down here. But why such foolish questions, Pen? You aren’t afraid of anything, are you?”

“There is only one thing I fear, Jim,” replied Pengelley, “and that is disgrace. I’ve always been timid about climbing; it’s a natural weakness that I cannot overcome no matter how hard I try. For a long time, I thought the feeling would wear away by enforced habit and constant practice, but in that hope I’ve been sadly disappointed. Ever since the night poor old Barney Dent was flung from the main topgallant yard, I’ve been oppressed by an unspeakable horror every time I go aloft, especially on that particular yard. Sometimes the terror makes me sick and causes me to vomit while I’m aloft; and then the reaction causes me to vomit again after I am safely on deck.

“Of course, everybody attributes it to seasickness, which is really chronic in some constitutions. In a sense it is seasickness, Jim. It is not actual fright. It is simply my stomach instead of my heart that gets in my mouth at such times, and it could not happen anywhere else except at sea; but it is a condition I can no more avoid or overcome than I can stop breathing and live.

“I know you will consider me silly and superstitious,” he went on, “but I know I shall never see the end of this passage, and before anything happens I want you to promise that you will do something for me after–after you reach Calcutta.” He faltered at the conclusion of the sentence, and I knew that his feelings were overwrought.

Although I placed no credence in his premonition, I realized that it was useless to try to reason him out of it. If he had been an ordinary, simple-minded old sailor oppressed by silly seasaws and ancient superstitions against capsizing hatch covers, striking the bell backward, or sailing on Friday, there might have been some hope. In that case, if he could not have been reasoned or ridiculed out of his groundless fears, he could have been kicked or cuffed out of them or otherwise left to steep in his own ignorance.

But Pengelley was different. He was a broad-minded, widely read, well-informed young man. I had never known him to harbor spooks or mental hallucinations, nor was he a victim of melancholia. In fact, he had always been regarded as the most cheerful of the four apprentices.

“If it is as serious as all that, Pen,” I said, for I was becoming alarmed for his safety by this time, “you had better lay up for a few days or until we run into fine weather again and your nervousness subsides. I am sure Captain Grummitt won’t insist on ordering you aloft if your life is endangered by it.”

“Jim,” he declared firmly, “I can’t do that. The other apprentices would despise me and my father would disown me. Please keep quiet about it,” he pleaded in genuine alarm. “Simply do as I wish you to.”

“But, Pen,” I insisted, “you are the bravest boy I ever saw to live through a horror like that for four years just to gratify your father’s whim. I am sure he would have withdrawn your indentures long ago and had you sent home if he had been aware, of the facts.”

But Pengelley was obdurate. All I could do under the circumstances was to humor him and appear to acquiesce in his plans, for he was really laboring under a dangerous mental aberration. His designs would have to be humored in order to be circumvented. I therefore pretended to act in accord with his wishes, but mentally resolved to frustrate his quixotic fancies of filial devotion even if it meant incurring his everlasting displeasure. I inwardly resolved to try not only to have Pengelley relieved, but, if possible, prohibited from going aloft during the remainder of the voyage.

“Well, Pen,” I resumed, “don’t be downhearted. We’ll run into fine weather in a day or two and the danger will be over. Meanwhile, whenever we have to go aloft, you stick close to me. That will encourage you and I will always be there to lend a hand.”

“Thank you, Jim,” exclaimed the boy with grateful fervency. “But before we separate I want you to promise that in the event of anything happening to me you will send this box to my sister Eunice, at Saint Ives. She knows of you already,” he added, thrusting a package into my hands as he spoke, “because I mentioned you to her in my last letter home from New York.

“In this package,” he went on, “there is a camphorwood box containing some letters and photographs, some private papers and trinkets, and the gold watch my father gave me when I left home. I know that if I am missing all my effects will have to be accounted for by the captain and owners of this ship. But in that case they would likewise have to be inspected, and the contents of this box are too sacred for that.”

“You can get Miss Primrose, the little missionary in Calcutta, to help you. She knows me well and I believe she knows you also. She can manage to have the package sent for you by special dispatch. Under the canvas wrapper around the box, you will find a letter addressed to my sister. I want you to send it to her together with another letter to be written by yourself.”

“Well, I’ll take your orders, Pen,” I replied, “and all the more willingly because I feel certain I shall never be required to carry them out.”

Pengelley wrung my hand warmly. “God bless you, Jim,” he exclaimed. “And now I want you to accept these trifles as a token of our friendship.” With that, he thrust into my hand a heavy gold; watch guard with a solid gold anchor pendant attached as a charm. I recognized the pieces and appreciated their intrinsic value and artistic merit, for I had seen Pengelley wearing them on special, occasions.

It was nearing seven bells now, and Pengelley and I crawled from beneath the sheltering enclosure of the inverted boat and descended to the slippery surface of the main deck. Pengelley went aft to take the time, and I dove into the forecastle to secrete my precious charge before the watch was called.

Returning to the deck, I proceeded at once to locate some of my; watchmates and arouse them to the fact that another furling match was about due. I could not think of taking in that big main-topgallant sail, however, without feeling concerned over Pengelley’s tragic premonition. There was great danger to anyone working aloft in the Late Commander because of the complete absence of any beckets, grab lines, or saving gear of any kind on her yardarms. The harrowing lessons of three tragic casualties on the previously run had made no perceptible mark on the hearts or minds of those responsible. No effort had been made to guard against future tragedies. She lacked even the most basic lifesaving attachments on the yardarms. This deficiency, because of the great girth of her principal spars and the immense spread and heavy weft of her enormous sails, made the Late Commander an extremely hazardous ship to manipulate aloft.

I tried hard to invent some lubberly trick, no matter how base, to prevent Pengelley from going aloft that night, but I was at my wit’s end and could not think coherently. There was no time to weave a plot or to execute it if found. The stroke of one bell found me still struggling with my inward terrors and with no hope of any design. In a few minutes, both watches were out and Tom Splicer was splashing around the deck roaring orders to everybody below and aloft.

There was no general muster, but within a few minutes all hands were hauling away on the main-topgallant running gear. Clewlines, leechlines, buntlines, and downhauls were all manned at once and the massive topgallant yard came creaking down handsomely to the topmast cap. The voluminous canvas came floundering, fluttering, and thundering with a tremendous straining and baffling uproar against the mighty tension of the gear.

Amid the momentary excitement and general din, I ceased for a time to worry about Pengelley; and when the tautened gear had been belayed and the braces steadied, I was among the first to lay aloft in response to the imperious order, “Tie ’er up.”

Upon reaching the masthead, I assumed one side of the bunt, with Big Mac for a side partner. With a forty-foot hoist on a sixty-foot spar, it was no child’s task to bunt that main-topgallant sail.

Moreover, it was always a desperate job, especially when running square, because the yard was rigged with old-fashioned quarter clewline blocks, there were no spilling lines, and the buntline lizards on the jack-stays were entirely too long. This left large quantities of slack canvas with which to contend. Consequently, there was always an immense wind bag to smother when the sail was brailed up.

When the watch had mustered along the yardarms and the gaskets were cleared, the huge bag bellied and bellowed above our heads as tense and rigid as an inflated balloon. The wet and hardened canvas was as unyielding as chilled boiler plate. Taking advantage of a momentary wind flaw in a lucky backsend of the ship, we all grabbed the slightly slackened canvas and, shouting encouragement to each other, made a united and desperate effort to smother the big wind bag and strangle it up snugly to the jackstay.

But in the next dive, the clews filled away again. In spite of the desperate exertions of ten strong men, the sail burst away with an exultant bang. And then, in the extremity of common danger, I heard a faint, wild, despairing cry and felt an ominous slackening of the footrope beneath my feet. Instantly a fearful dread froze my heart. Where was Pengelley? Had he purposely eluded me in the darkness and brought about the terrible fulfillment of his premonition? Trembling at the harrowing thought, I returned to the hazardous duty before us; and, after a few more daring attempts, we finally succeeded in overpowering the raging sailcloth and bunched it up securely on the swaying yard.

After passing the tail stop of the bunt gasket to Big Mac, I clutched the convenient warp of the topgallant backstay and slid, like a plummet to the topgallant rail. As I leaped to the deck, I met Jones, the junior apprentice, a muffled and impersonal shape in the darkness. I recognized him by his voice, and he probably knew me by my hasty and vigorous actions.

“That you, Williams?” he inquired.

“Yes, it’s me,” I responded. “Who fell?”

“Pengelleyl He wants you,” he replied in a horrified tone. “They carried him into the cabin and the cap’n says he’s dyin’. He’s been callin’ for you.” The young apprentice subsided with a smothered sob, and I made my way with bursting heart to the cabin. I pulled the heavy teakwood door open without any preliminary knock and strode unceremoniously into the forward cabin. It was likewise the officers’ mess room; and there, bolstered up on a berth mattress on the big mess table lay the broken frame and tortured body of the dying boy.

At the head of the table stood Captain Grummitt, a chastened look softening his wooden features. Beside him stood the steward, striving awkwardly to minister to the last earthly needs of the passing spirit. Ranged alongside the mess board were four able seamen standing in reverent silence. They were the rescue squad that had brought Pengelley into the cabin. Above, in the skylight, the telltale compass wobbled unsteadily with the yawing of the ship; the marine clock in the alcove ticked the fateful seconds away with relentless beats; and outside the storm wind howled a mighty greeting to the departing soul.

As I stood near the entrance, sou’wester in hand, Captain Grummitt beckoned me to the side of my shipmate. Stepping quietly to the head of the table, I bent reverently over the dying apprentice and listened attentively to his labored breathing to catch any parting words.

Pengelley lay perfectly still for a while. His hands were cold as ice, his eyes partly closed, and his handsome features, now distorted by mortal anguish, were as white as chiseled marble. Only the painful and irregular breathing and the slight twitching of the pallid lips after each feeble gasp indicated that the spark of life still glowed faintly.

“Do you know me, Pen?” I asked, pressing his cold hand firmly in mine.

The dark eyes opened slowly and a slight flash of glad recognition illumined the pale features. The bloodless lips moved inaudibly and I bent closer to catch the whispered words.

“You’ll remember, won’t you, Jim? The package and the letter?”

“Surely, Pen,” I murmured hoarsely. “I’ll do all I have promised.”

“Thank you, Jim,” he faltered once again. ‘I’m glad—you—came. Now—I am—content.”

Then the weary eyelids drooped again over the fading orbs, the death pallor deepened to an unearthly whiteness, and for fully a minute the labored breathing ceased. Then, just as Captain Grummitt was about to make an inspection to detect any lingering spark of life, Pengelley’s whole body became suddenly convulsed by a raging spasm of supreme agony. His eyes opened wide, staring and sightless. His classical features were fearfully distorted in an excruciating horror of unutterable anguish. His head rocked violently from side to side and raised spasmodically from the pillow in an uncontrollable ecstasy of intense soul-racking pain.

“Lord! Lord! Help me!” he shrieked in the terrifying accents of mortal extremity, and with that great agonizing appeal a surging hemorrhage burst the internal barriers of life. The pent-up flood poured forth from mouth and ears and nostrils in crimson streams, the raised head fell back limply to the waiting pillow, the contracted features relaxed in a smile of ineffable relief, a parting sigh of weary contentment escaped the colorless lips, a settled attitude of eternal repose stole over the stalwart form on the table, and all was still.

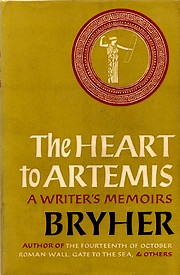

dreamed about Bokhara, a fabulous city that was then more difficult to access than Tibet. I opened my eyes upon the end of not only the nineteenth century but of a second Puritan age. An epoch passed away while I was learning to speak and walk. Its influence remains as the start of memory and as a measuring rod for progress that even Edwardian survivors lack.

dreamed about Bokhara, a fabulous city that was then more difficult to access than Tibet. I opened my eyes upon the end of not only the nineteenth century but of a second Puritan age. An epoch passed away while I was learning to speak and walk. Its influence remains as the start of memory and as a measuring rod for progress that even Edwardian survivors lack. A lovely acknowledgement from the introduction to Geoffrey Vickers’ 1970 book,

A lovely acknowledgement from the introduction to Geoffrey Vickers’ 1970 book,  That winter, the old General moved from the rooms he had rented from the free mulatto, Wormley, in I Street to Cruchet’s at Sixth and D Streets. His new quarters, situated on the ground floor–a spacious bedroom, with a private dining-room adjoining–were convenient for a man who walked slowly and with pain; and Cruchet, a French caterer, was one of the best cooks in Washington.

That winter, the old General moved from the rooms he had rented from the free mulatto, Wormley, in I Street to Cruchet’s at Sixth and D Streets. His new quarters, situated on the ground floor–a spacious bedroom, with a private dining-room adjoining–were convenient for a man who walked slowly and with pain; and Cruchet, a French caterer, was one of the best cooks in Washington. There were seven jars attached to the framework in the centre of the room and as soon as the chief’s sons-in-law had arrived and hung up their cross-bows on the beam over the adventures of Dick Tracy, they were sent off with bamboo containers to the nearest ditch for water. In the meanwhile the seals of mud were removed from the necks of the jars and rice-straw and leaves were forced down inside them over the fermented rice-mash to prevent solid particles from rising when the water was added. The thing began to look serious and Ribo asked the chief, through his interpreter, for the very minimum ceremony to be performed as we had other villages to visit that day. The chief said that he had already understood that, and that was why only seven jars had been provided. It was such a poor affair that he hardly liked to have the gongs beaten to invite the household god’s presence. He hoped that by way of compensation he would be given sufficient notce of a visit next time to enable him to arrange a reception on a proper scale. He would guarantee to lay us all out for twenty-four hours.

There were seven jars attached to the framework in the centre of the room and as soon as the chief’s sons-in-law had arrived and hung up their cross-bows on the beam over the adventures of Dick Tracy, they were sent off with bamboo containers to the nearest ditch for water. In the meanwhile the seals of mud were removed from the necks of the jars and rice-straw and leaves were forced down inside them over the fermented rice-mash to prevent solid particles from rising when the water was added. The thing began to look serious and Ribo asked the chief, through his interpreter, for the very minimum ceremony to be performed as we had other villages to visit that day. The chief said that he had already understood that, and that was why only seven jars had been provided. It was such a poor affair that he hardly liked to have the gongs beaten to invite the household god’s presence. He hoped that by way of compensation he would be given sufficient notce of a visit next time to enable him to arrange a reception on a proper scale. He would guarantee to lay us all out for twenty-four hours.