Ben Daniel Piazza, we learn from his bio on The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture, “was born on July 30, 1933, in Little Rock (Pulaski County) to Charles Piazza, a shoe repairman, and Elfreida Piazza, a homemaker. He was the eighth of nine children, having two sisters and six brothers.”

Ben Daniel Piazza, we learn from his bio on The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture, “was born on July 30, 1933, in Little Rock (Pulaski County) to Charles Piazza, a shoe repairman, and Elfreida Piazza, a homemaker. He was the eighth of nine children, having two sisters and six brothers.”

Alexander Gallanti, the narrator of The Very Strange and Exact Truth, is the son of Rudolfo Gallanti, a Little Rock shoe repairman, and one of eight children. “This is a work of fiction, and therefore the characters and events in this work are fictional,” states the Author’s Note at the start of the book, but it’s clear that the autobiographical elements of this, Piazza’s first and only novel, are many.

You’ve probably seen Ben Piazza. His entry on the Internet Movie Database lists over 90 television and movie productions in which he appeared between 1957 and 1991. He started acting while attending Princeton, went to Broadway and then Hollywood, was considered at first a promising lead, something like a young Brando or Newman, but became more of a character actor as time went on. In later years he often played a stereotypical upright and uptight establishment man, as in a memorable restaurant scene in “The Blues Brothers: The Movie.”

You’ve probably seen Ben Piazza. His entry on the Internet Movie Database lists over 90 television and movie productions in which he appeared between 1957 and 1991. He started acting while attending Princeton, went to Broadway and then Hollywood, was considered at first a promising lead, something like a young Brando or Newman, but became more of a character actor as time went on. In later years he often played a stereotypical upright and uptight establishment man, as in a memorable restaurant scene in “The Blues Brothers: The Movie.”

He took over from George Grizzard as Tom in the original production of Albee’s “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” and appeared in several other Albee plays. The Very Strange and Exact Truth is dedicated to Albee. He also wrote and produced a number of his own plays in New York and Los Angeles. He died at just the age of 57, of cancer, in 1991.

If Alexander Gallanti bears any resemblance to the young Ben Piazza, he had a strong theatrical streak early on. In a climactic scene in the novel, Alexander fantasizes about receiving a standing ovation for his rendition of “We Gather Together” at his junior high school Thanksgiving pageant, and when his mother is struck down with a stroke, he insists on wearing his Pilgrim costume for days afterward. And late in the book, Alexander and his younger sister and brother insist on applying great gobs of makeup to their mother’s half-paralyzed face before hauling her in a wagon to a moviehouse, despite whispers of passers-by that she looks like a clown.

The Very Strange and Exact Truth is a heart-breaker: first Alexander’s father dies, then his mother becomes a mute and limp shadow of herself, suffers for months, and dies, too. Alexander and his younger siblings are split up and he is sent in the end to a boarding school. The warm, affectionate world of his early childhood, in a house built by his father, a kitchen warmed by his mother’s cooking, and a yard full of vegetables, fruit trees, chickens, and flowers is taken apart bit by bit. Two older brothers leave to fight in World War Two. An older sister marries and moves across town. In the end, nothing is left of the world he first knew.

The Very Strange and Exact Truth is a heart-breaker: first Alexander’s father dies, then his mother becomes a mute and limp shadow of herself, suffers for months, and dies, too. Alexander and his younger siblings are split up and he is sent in the end to a boarding school. The warm, affectionate world of his early childhood, in a house built by his father, a kitchen warmed by his mother’s cooking, and a yard full of vegetables, fruit trees, chickens, and flowers is taken apart bit by bit. Two older brothers leave to fight in World War Two. An older sister marries and moves across town. In the end, nothing is left of the world he first knew.

But well before any of the tragedies, Alexander is aware that there are things going on that are not of the child’s world. Piazza’s viewpoint was undoubtedly influenced by Albee, Tennessee Williams, and other contemporary American playwrights whose works he performed, and it shows in passages like the following, in which Alexander feels a strange attraction to a man and woman he sees through their bedroom window, sleeping naked on a warm summer morning as he makes the rounds of his paper route. Eventually, he feels so drawn that he goes behind some bushes, takes off his clothes, and attempts to enter their house and climb into bed with them, only to find all the doors locked.

I went back in the bushes and put my clothes on and my paper bags and delivered the rest of the papers as best I could after all that. I felt very badly about them not wanting me after I had found my secret with them. I still watched at their window every morning until summer ended and I gave up my paper route. But it was different because I knew that they didn’t want me at all and that I would never be with them. I would always be on the outside of their house, looking in.

It’s hard to imagine that scene and that last paragraph appearing in any novel written before Salinger, Albee, and Williams. Or the story of Jesus Elizabeth Jones, the son of the family’s housekeeper, who runs away one day, leaving his mother a note saying that he has bought a pair of red high heels and is wearing them on the bus to Chicago.

There are numerous scenes like this in The Very Strange and Exact Truth, scenes that are certainly too symbolic to have been autobiographical. After their mother’s stroke, for some unexplained reason Alexander and the younger children are left for a few days on their own, and they make up their own country as they play each day in the back yard:

They made up rules about the new country. In this new country nothing bad could ever happen to anyone because there were lots of angels looking out for everyone. And in the new country nobody got sick or died and everyone loved everyone else. In the new country you could holler and scream and say whatever you wanted to and all anybody ever ate was candy or ice cream and cake.

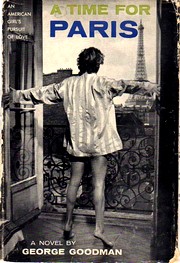

Although The Very Strange and Exact Truth earned good reviews when it was first published in 1964 and was aided by enthusiastic blurbs from Steinbeck (“A darn good book”), Williams (“A truly brilliant novel”), and Albee (“The sort of novel that will leave you a changed person for having read it”), it sold only moderately well in hardback, received one paperback release (with a completely misleading cover), then vanished. AddAll.com lists 66 copies for sale online, with most of those starting at $25 and up–even for the paperback version that originally retailed for 60 cents.

I was alerted to the book by the enthusiastic reviews on Amazon, but I was a little reluctant to commit to it after a quick scan told me that it was about childhood and death. But I quickly grew engrossed by the power of Piazza’s imagination and prose and polished off most of the book in the course of a trans-Atlantic flight. It’s a remarkable work and makes me regret that Piazza never found time to come back to fiction after his first attempt. The Very Strange and Exact Truth is a fine, beautiful, memorable novel.

Donald Schon’s

Donald Schon’s

Reading Isa Glenn’s novel,

Reading Isa Glenn’s novel,  Glenn published a total of eight novels in the space of nine years. Two–

Glenn published a total of eight novels in the space of nine years. Two–

the book itself or the fact that it was published by the Princeton University Press. Purportedly the “twenty-five year record of ‘the finest aggregation of men that ever spent four years together at Old Nostalgia'” as penned by the class secretary, “Tubby” Rankin,

the book itself or the fact that it was published by the Princeton University Press. Purportedly the “twenty-five year record of ‘the finest aggregation of men that ever spent four years together at Old Nostalgia'” as penned by the class secretary, “Tubby” Rankin,  I picked up

I picked up  “In the summer of 1963 I bought a 1941 Lincoln limousine in New York, so that I might be chauffeur in California to the few remaining dignitaries in my family,” William Saroyan explains at the start of

“In the summer of 1963 I bought a 1941 Lincoln limousine in New York, so that I might be chauffeur in California to the few remaining dignitaries in my family,” William Saroyan explains at the start of  In

In  Riffling realizes he is an Out-of-Sync, as is Miss Dunnette, the gorgeous red-headed librarian with whom he heads of on his journey. They soon locate Hafter’s former lover, Emma, a 70-year-old toker who still lives on the old farm where Hafter established Gallitzin College in the barn and pulled together a Utopian community of fellow Out-of-Syncs back in the 1920s. Fifty years ahead of its time, Hafter’s commune was awash in organic veggies, free love, and home-grown hemp, and everyone worshipped an enormous painting of a nude black woman with a sunflower bursting from her crotch.

Riffling realizes he is an Out-of-Sync, as is Miss Dunnette, the gorgeous red-headed librarian with whom he heads of on his journey. They soon locate Hafter’s former lover, Emma, a 70-year-old toker who still lives on the old farm where Hafter established Gallitzin College in the barn and pulled together a Utopian community of fellow Out-of-Syncs back in the 1920s. Fifty years ahead of its time, Hafter’s commune was awash in organic veggies, free love, and home-grown hemp, and everyone worshipped an enormous painting of a nude black woman with a sunflower bursting from her crotch. Ah, there’s nothing like a dose of Georges Simenon to remind us of the worms lurking just beneath the surface of normality. He really was a master of finding that loose thread that can unravel the whole fabric of one’s existence with a simple tug.

Ah, there’s nothing like a dose of Georges Simenon to remind us of the worms lurking just beneath the surface of normality. He really was a master of finding that loose thread that can unravel the whole fabric of one’s existence with a simple tug. I probably would have filed

I probably would have filed

Marshmallows have more substance than this book. Stalwart Yale-grad and Korean War vet Fred Holland sails off to serve in the American Embassy in London. He and his chum spot pretty Sally White, also of good WASP stock, boarding their ocean liner. Fred chats up Sally, who turns out to be an old but distant acquaintance from summers on the island in Maine.

Marshmallows have more substance than this book. Stalwart Yale-grad and Korean War vet Fred Holland sails off to serve in the American Embassy in London. He and his chum spot pretty Sally White, also of good WASP stock, boarding their ocean liner. Fred chats up Sally, who turns out to be an old but distant acquaintance from summers on the island in Maine.