· Excerpt

· Editor’s Comments

· Locate a Copy

Excerpt

At Fairbanks he learned that he was not to be allowed to deliver at Minneapolis, as he had planned, a public address on his trip. Security reasons, said the President, who had to bottle him some way, and perhaps in this instance was not altogether wrong, but was getting tired of the way in which, no matter how we had defeated, the man came bouncing back. Report to Washington first.

There was also an offer to speak over the radio on October 26th. Well, thought Tom, that would take care of the bottling operation, if he had his way.

Unfortunately, the world, like the mouse’s tale in Alice, has a tendency to dwindle away to nothing, when you got back to America, except that in this case it was no mouse, but a lion they had by the tail. Didn’t they realize that?

He glanced at the mountains, whose snows were gold with sunset. Who was it, somewhere during his travels, a wit, so perhaps it had been in Turkey, where Noumen Bey, the Foreign Minister, had seemed, like his mind, a little sad, a little cynical, very strong, and very subtle, had referred to life in America as “Life behind the Gold Curtain”?

He could not remember, but he remembered the remark.

There were forces abroad (the war had let them out, as ghosts come out in a thunderstorm), out there, across the seas, which would have to be reckoned with, and which, if they were ignored, would distrub the whole world.

The trip had taken forty-nine days. That was almost exactly the length of that other trip he had taken, during the election campaign. That had not occurred to him before, but now he saw that they were the same trip, or at any rate, one on one side of the mirror, and the other through it; the one through a world that preferred to dream, the other through a world that was the nightmare America feared. It is true: the dream of reason produces monsters. But in this case it was an irrational dream. In this case it was the monsters who had reason on their side.

America is fenced with mirrors. They are our spiritual defence against the truth. And since we refuse to shatter them, there was nothing to be done now, but wait until they had been shattered from the other side, which would happen soon enough; though what would the world fine on the inside, then, but broken glass? The creature was shrivelling away from sheer mirror vanity. It was too late.

It had no dignity. Therefore it was a comedy, but only because one forced one’s self to smile. For it was also a tragedy, which broke for good hearts of those who still loved the place, no matter how ashamed they might be of what their government had done. There are a good many of those, and always will be, for the land means everything, even when those who rule it mean little or nothing at all. So it is sometimes nobler to be Tom Fool. Nobler, and of better use.

Editor’s Comments

David Stacton seems, from his Wikipedia biography, a fascinating case of the neglected writer. In the space of eight years, between 1957 and 1965, he published eleven historical novels, ranging in subjects from ancient Egypt (On a Balcony) and medieval Japan (Segaki) and India (Kaliyuga) to the Cannes film festival (Old Acquaintances). He also wrote a good share of pulp fiction under pseudonyms such as Bud Clifton, Carse Boyd, and David West. He died at the young age of 42, having lived a fairly itinerant life, and his work quickly vanished from public and critical sight.

Among Stacton’s works was what he referred to as his “American triptych”: A Signal Victory, a novel about the Spanish conquest of Mexico; The Judges of the Secret Court, about the assassination of Lincoln and John Wilkes Booth’s flight and death; and Tom Fool, about Wendell Wilkie, the unlikely Republican presidential nominee. Having a long-standing interest in FDR, I thought I would start my investigation of Stacton by trying out this novel about the man who gave him his toughest competition in all his four presidential campaigns.

Wilkie came into the 1940 Republican convention with virtually no organization and absolutely no delegates, but a combination of strong support from several influential newspaper publishers and a three-way gridlock among the official candidates — Robert Taft, Thomas E. Dewey, and Arthur Vandenberg — enabled him to emerge after six ballots as the nominee. The old guard Republican party, in Stacton’s words, “wanted something like the Bourbon Restoration in Naples. They wanted to be reactionary. They wanted to punish.” Instead, the convention led to, in the words of one newspaper writer, “the most revolutionary thing the Republican Party had done since the nomination of Lincoln.”

Stacton portrays Wilkie as something of a holy fool. His motive is pure and simple — protect the land and the people from the many dangers of “that man”. Unfortunately, he quickly finds that modern politics is less a crusade than a circus, and no different from the lions and elephants, he is at the mercy of his handlers:

He was beginning to learn how much the professionals hated him. That left him the people. Unfortunately, as his advisers told him, it was first necessary to get to the people. He had to turn to such of the professionals as he could gather in, after all.

And so he winds up with a bevy of professionals at a retreat in Colorado. “The term is religious,” writes Stacton, “but the event is not. The event had about as much spirituality as a locker-room conference twenty minutes before the big game. It also had the same jockstrap, hard soap, sheep dip, and sweaty-armpit smell.” From the retreat, the Wilkie circus then takes off on an epic train journey around the country. Unlike Truman’s legendary whistle-stop campaign, Wilkie’s was less a matter of plain speaking and more one of media manipulation. Professionals such as “Sideboard,” who ghost-writes articles and forces canned speeches on Wilkie, or the Pattersons, who “had traits, but no character.” “Indeed,” Stacton continues, “they were not people at all, only a bank account and that odd, vacant look in their eyes.”

Wilkie’s crusade is not just a simple “back to roots” plea for folk democracy. He might argue against Roosevelt’s third term, but he shares FDR’s abhorrence of isolationism:

He could only tell such people that theirs was not the only country in the world, and that it behoved them to act accordingly. But that is never a popular message. Xenophobia saw to that, xenophobia is an act of ignorant pride, and pride, after all, goeth before a whole man.”

Still, Wilkie manages to misread the people’s will almost as consistently as the professionals do. He finds himself booed in Michigan: “… the workers, though better paid than the office staffs above them, were sullen with class hatred. He had never seen class hatred before.” He tells his listeners, “… if we do not prevail this fall, this way of life will pass.” But “Half the people … didn’t care. All they wanted was their salaries and hand-outs.” This half was already lost, at least in Stacton’s eyes, and with Wilkie’s loss, the other half — the good people of the land — lose their last chance:

The great ranches are going. The farms are gone. The highways lead nowhere; and the suburbs are worse and worse built; they cost more and more; and everybody drives.

The second half of Tom Fool seems a bit deflated. Despite his defeat, Wilkie carries on. Roosevelt sends him around the world as a personal investigator, a series of journeys Wilkie described in his 1943 best-seller, One World. But as Stacton characterizes the trip, which in the novel mirrors Wilkie’s campaign tour as precisely as described in the excerpt above, it is a journey through lands as spiritually defeated as America. The Soviets are neither the great red enemy nor the great hope for mankind. The Chinese masses are pulled between two leaders — Chiang Kai-Shek and Mao — more concerned with ambition and ideology than their peoples’ needs. Fascism comes to seem only slightly the greater of two evils. Wilkie’s vision has no outlet, even if Stacton considers it “Nobler, and of better use.”

The problem with Tom Fool, though, is that it claims to be a novel and yet comes across as a tract. Stacton may write that the Pattersons have no character, but Wilkie himself is more spirit than substance. The figures in this book have attitudes and positions, not features and habits.

In a review of another Stacton novel, Naomi Bliven wrote in the New Yorker, “Although Mr. Stacton is a good writer, his work is extremely disheartening, because he will indulge his talent for twisting perspectives so as to make human life appear to be nothing more than a grotesque and malignant practical joke.” This tone certainly pervades Tom Fool, and by the end of Wilkie’s journeys, the reader grows weary of Stacton’s relentlessly acerbic commentary. One biographer noted that Stacton’s characters

… are often two-dimensional figures, selected to illustrate a thesis, and drawn without much sympathy or understanding. By way of compensation there is his baroque and waspish style, studded with epigram, apothegm, and aphorism, ‘one of the most massively complex and convoluted styles of our time.’

In Tom Fool, however, this style bludgeons narrative, protagonist, and reader, leaving all with various scratches and bruises. Imagine one of Gore Vidal’s wonderful historical fictions, such as Lincoln, with all the intelligence and insight but almost none of the grace and wit. Or a cocktail party hosted by a brilliant but overbearing host — who drives his guests to the bar for another martini to tune out their host’s insufferable banter.

I plan to give Stacton a try again sometime. But if you care to give Tom Fool a try … well, then, you’re no wiser than Wilkie was.

Locate a copy

Tom Fool is fairly rare. Neither Amazon.com nor Amazon.co.uk lists any copies for sale, so if you’re desparate to read this book, you’ll need to search for it at a major university library or consider plunking down $75 for one of the few copies listed on AddAll.com.

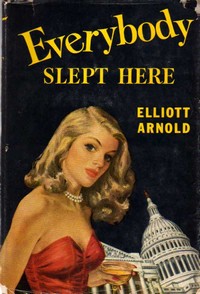

Moskowitz mentions that the club has William Wilson’s

Moskowitz mentions that the club has William Wilson’s  Elliott Arnold’s

Elliott Arnold’s  Many of the characters Arnold sketches are one-dimensional and forgettable, but he does a marvelous job with Willy and his wife. Willy wears a girdle to rein in his gut and relaxes by sewing women’s’ dresses, and serves his time in uniform finding the best Scotch, the finest steaks, and whatever other amenities the Congressmen and generals need. It would be easy to make him preposterous and contemptible. Instead, Arnold is able take us past first impressions and show that he is also an honorable man in his own way, and a tender husband to his fragile wife.

Many of the characters Arnold sketches are one-dimensional and forgettable, but he does a marvelous job with Willy and his wife. Willy wears a girdle to rein in his gut and relaxes by sewing women’s’ dresses, and serves his time in uniform finding the best Scotch, the finest steaks, and whatever other amenities the Congressmen and generals need. It would be easy to make him preposterous and contemptible. Instead, Arnold is able take us past first impressions and show that he is also an honorable man in his own way, and a tender husband to his fragile wife.