Excerpt

When he had come under Mr. Henry Harcourt’s personal supervision, Willis could not help see that he was regarded in a new light by everyone in the plant. The workmen he had always known were as friendly to him as ever. Labor, he was to learn later, seldom could be made to take an interest in management; but is was different in the office, where people he had known through many summers now gave him appraising, suspicious looks. Willis could sympathize, because he had been pushed forward above the heads of many who had been working there for years. He knew that Mr. Briggs in the sales department disapproved of his promotion. Mr. Briggs had told him that he had worked at Harcourt for fifteen years before he had been pulled off the road to be assistant sales manager. You worked your way up from the bottom in those days, and the way to learn business was doing business, instead of studying at some school. Mr.Hewett had a more generous attitude, perhaps because he knew that his days at the mill were almost over. Mr. Hewett often told Willis to watch this or that, because Willis might be in his shoes some day. He spoke only half seriously, and Willis was under no illusions, since it would obviously be years before he could ever manage Harcourt’s.

His father’s attitude was what disturbed Willis most.

“Son,” his father said on evening, “I had a friend once, out in San Francisco. We’d been working together building dams for Pacific Gas and Electric, and then he joined up with Standard Oil. I remember when he took the boat to China. We had quite a lot of drinks the night before, telling each other what we were going to do, because we were pretty young then, and kids all want to be American heroes. Now I suppose you want to be one, too, but I don’t any more. It’s hard enough to try to be what you are. Well, anyway, I stood on the pier seeing Bill off, and I had quite a head that morning. I was there quite a while watching the ship pull out, seeing it get smaller, and I knew Bill was going somewhere I wasn’t ever. Well, it’s the same with you. Only just remember this one thing. Every now and then take a look at yourself, and try to be sure where the hell you’re going. I can’t tell you because I wouldn’t know.

Editor’s Comments

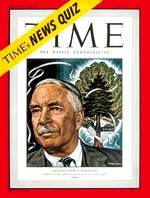

For a while in the middle of the last century, John P. Marquand was the most successful novelist in America–successful in consistently hitting the top of the best seller lists as well as in earning critical recognition, including the Pulitzer Prize for his 1937 novel, The Late George Apley. By the time he published Sincerely, Willis Wayde, however, both his sales and literary reputation were on a decline–one that’s continued till today. Aside from his early magazine fiction and his Mr. Moto series of detective novels, Marquand’s books had been subtle satires of East Coast–and particularly Boston–society. His approach and subject matter probably seemed a bit soft and a bit stale compared to that of Grace Metalious or Norman Mailer.

Ironically, as Millicent Bell writes in her authoritative biography, John P. Marquand: An American Life:

Marquand first thought of Sincerely, Willis Wayde as a novel that would firmly put behind him the lost world of early twentieth century America. He planned to depict a hero “swatting it out with life, strictly in the urban world of today–somebody on the down-wind side of the point of no return.”

C. Hugh Holman called Sincerely, Willis Wayde Marquand’s “least typical book,” and several prominent features do separate this novel from his other serious works. Many of Marquand’s narratives rely heavily on the use of flashbacks to tell the story; here, he looks relentlessly forward as we follow Willis Wayde’s rise from being the son of a factory engineer to the CEO of a major industrial conglomerate. Unlike other Marquand protagonists, Willis never puts up seriously struggle with his own doubts. He takes quick note of them and then moves on. And Sincerely, Willis Wayde is more a novel of business than society.

In this case, the business is that of industrial belting. Marquand shrewdly chose a product that had no consumers but other businesses–manufacturers, supply companies, supermarket chains. This allows his character to stay immersed in a world where rational choices based on bottom lines, rather than that of individual purchases influenced by unpredictable psychological factors. Which is fortunate for Willis, for whom psychology is never his best subject: “It was a relief to meet someone like Mrs. Jacoby, who did not have the Harcourt’s sentiments, because anyone with common sense knew that sentiment had no place in industrial transactions.”

Starting out as a protégée of Mr. Henry Harcourt, the aging head of Harcourt Mill, a family business rooted in Marquand’s favorite fictional town of Clyde, Massachusetts, Willis might have stayed with the firm, slowing working his way up the ladder like Mr. Briggs or Mr. Hewett. But he has also grown up in an ambiguous relationship with Harcourt’s son and grandchildren, sort of an unofficial foster child or poor cousin. Bess Harcourt, the , flirts with Willis at times as they become adults, but sticks with convention in the end, marrying a dull but wealthy heir.

A different man–a traditional Marquand hero, perhaps–would have shrugged and soldiered on, sadder but wiser. Willis’ father, a better judge of human nature, counsels him to be realistic:

“You’re trying to be something you aren’t,” he said. “You watch it, Willis. You keep on trying to be something you aren’t, and you’ll end up a son of a bitch. You can’t help it, if you live off other people.”

“I don’t get your point. I honestly don’t,” Willis said.

And he truly doesn’t. Instead, he lands a job with a high-priced New York consulting firm. And from that point on, Willis never looks back. He comes across a struggling belting factory and insinuates his way into a position with the firm. Through hard work and dedicated boosterism, he not only saves the company but takes it to a position from which he orchestrates a merger with Harcourt Mills.

Willis strives to be the very model of a modern major businessman of the late Industrial Age. He rises early every morning, does twenty push-ups, and reads fifteen minutes from Dr. Eliot’s Five-Foot Shelf. He joins the Rotary, fancies himself a fine speaker, and moves through a series of bigger and better houses and cars. And he comes to hold model opinions of where American culture was going:

They did not like their country in spite of all the fine things America had done for them, such as the education it had given them and the chance to sell their books and motion-picture rights for enormous prices. They did not like America in spite of the opportunity America gave them to acquire lovely homes and have their pictures in Life and Time. These people were constantly sneering at solid institutions, snapping at the very hand that fed them. When they wrote about business, they looked upon people who earned an honest dollar by selling products, running banks or production lines as crass materialists, devoid of ideals and social conscience. Businessmen in all these novels were ruthless and very dumb. Willis often wished that he might have a talk with some of these writers. He wished that he could show them that men who ran factories and sold the products and dickered with bankers, tax examiners and labor union organizers were not as dumb as a lot of novelists who always seemed to be at Palm Beach with some blonde.

Eventually, Willis’ earnest pursuit of profit and efficiency lead him to sacrifice Harcourt Mill itself. Its aging plant and workforce can’t compete with newer, larger factories, despite his promise to the Harcourts–and himself–that “He certainly would do everything he could–within reason–to keep it open.”

That “within reason” is a wonderful and telling touch by Marquand. One reason his reputation with critics and readers has suffered in the last half century is that, despite a sometimes wooden prose style, he is often too subtle and wise for his own good. Time’s reviewer compared Willis to George Babbitt, but Marquand was never one for stereotypes. No one really goes through life without self-reflection. Even with his strong drive for success, Marquand shows Willis constantly checking himself–checking if he’s wearing the right clothes, saying the right things, making the right choices.

The problem is that these are all glances. Genuine doubts penetrate to one’s core, and these would just slow Willis down. So when he stops to search his soul, it’s more in the way you pat your pockets to reassure yourself that the car keys are still there. Marquand deftly conveys this conscientious moral blindness in the following passage as Willis prepares to tell the Harcourts that he’s going to close their family business:

The art of persuasion, Willis believed, was the very keystone of American business and the basis of American industrial prestige, and he was never more convinced of its importance than during his talk with Bill and Bess. Without exaggeration, never in his life had he so keenly wanted two people to understand and sympathize with his point of view and to agree with his conclusions. It would have been unthinkable to have quarreled after so many years. It was a time for a sincere interchange of reaction, a time when every question must be answered.

The strength of his approach, as he talked to Bill and Bess, lay in his sincere sympathy.

Capitalism, as Marquand portrays it, is not evil. Rather, it is more like a parallel universe, one with laws that are simply incompatible with the world of emotions, art, and traditions. When Willis finds himself in the latter world, as in the novel’s final scenes, where he struggles to enjoy (as a model successful tourist) a long-awaited vacation in Paris with his wife, Marquand shows what a sad and dull refugee he is. Away from the office and boardroom, Willis is like an actor without a part. He just moves around the stage getting in everyone’s way. You could say that the novelist of society ultimately wins out over the novelist of business in Sincerely, Willis Wayde. No one gets to stay in the office forever.

I consider Marquand one of the very few 20th century American novelists who writes like a grown-up, and I don’t want to close this review without noting that Sincerely, Willis Wayde also features one of the better portraits of a marriage since that other classic novel of business colliding with society, William Dean Howells’ The Rise of Silas Lapham. Willis’ wife, Sylvia, sees him more clearly and realistically than he ever does himself. Yet she also understands that she wants the comforts and luxuries that his ambition brings to their marriage and respects his talents too much to skewer him. In that way, she exemplifies maturity in Marquand’s eyes. “Mature people,” he once said, “are happier. At least they can rationalize the world in such a way that they are not going to beat their heads against a wall.”

The critic Maxwell Geismar wrote that, “Mr. Marquand knows all the little answers. He avoids the larger questions.” I think this insults Marquand’s intelligence–and Marquand’s respect for ours. Large questions about how one can reconcile business demands with human needs can be seen throughout Sincerely, Willis Wayde. It’s to Marquand’s credit that he knows most readers are smart enough to know there no simple answers.

Other Comments

- · Harlan Ellison, who wrote on his website:

- That Marquand continues to be overlooked is nothing less than criminal. He’s one of the few authors I’ve read that’s skewered institutions without mocking the troubled plights of his protagonists. Truly the harder road to travel. His characters are all too human in the foolish decisions they make. His married couples are astutely observed, steeped in the worst of compromises. Remarkably, Marquand was criticized for chronicling flatline heroes, but I can’t think of another author that’s dared to display the harsh undertow of comfy middle class life quite like him. Too many people trundle through life without even the inkling of an inner revelation. And the delicate decision of whether to watch haplessly as someone destroys herself or to intervene and scare them straight becomes a tricky ethical tightrope.

- · Terry Teachout, on his About Last Night blog:

- Babbitt with a backstory. This undeservedly forgotten 1955 blockbuster follows a New England businessman along the twisty road that leads from youthful idealism to mature vengefulness. Less subtle than Point of No Return, Marquand’s masterpiece, it offers a harsher, explicitly satirical view of life among the capitalists, and though Marquand’s Lewis-like portrayal of his anti-hero’s philistinism is a bit heavy-handed, I can’t think of a more convincing fictional description of the high price of getting what you think you want.

- · John Kenneth Galbraith, in the New York Times, from 1984:

- Neglected also is the modern corporate executive, the university-trained managerial type, wherever he lives. Thirty years ago – in 1955 – John Marquand made a brilliant beginning on this task with Sincerely, Willis Wayde, a novel that did not receive the attention it deserved from being, I think, too fully abreast of its time. Willis is a highly competent, soundly schooled, relentlessly ambitious, deeply offensive graduate of the Harvard Business School; he brings the best in modern management techniques to bear on the Harcourt Mill in Clyde, Mass., an old and distinguished manufacturer of industrial belting. He also brings off a greatly advantageous merger, moves the headquarters to the Middle West and, eventually, as part of a very intelligent strategy – strategic planning even then – abandons the original New England operation.

- · Time, 28 February 1955

- …. Marquand manages a highly skillful double-switch with the reader’s emotions. Early in the book, he smoothly turns the nice youngster into a glossy horror; later on he turns the horror into a rather sad character who compels sympathy. Novelist Marquand’s plot may sag at points, but the caricature of his hero is fascinating, down to the last page, when wise and forbearing Sylvia tucks in her husband with a kiss and a Nembutal. Perhaps the most pathetic thing about Willis Wayde is that, in his own peculiar way, he believes in what he is doing, is sincere even in the dreadful, calculating little social-business notes he always signs: Sincerely, Willis Wayde.

- · F. H. Guidry, Christian Science Monitor, 24 February 1955

- Mr Marquand’s masterful ability to delineate mood-creating detail in both setting and character is widely acknowledged. One can “walk in imagination” with his people, not only with a pleasing sense of compassion but with an agreeable awareness of irony as well.

Find Out More

Locate a Copy

Sincerely, Willis Wayde, by John P. Marquand

Boston: Little, Brown, 1955

Hermes Nye was born in Chicago, but became a legendary East Texas character: a lawyer, folksinger, folklorist, novelist, humorist, and local liberal activist. Nye clearly never took anything, including himself, too seriously. When, in the midst of the 1960s folk boom, he published a guide to folk songs, he gave it a triply-redundant title that included its own punchline:

Hermes Nye was born in Chicago, but became a legendary East Texas character: a lawyer, folksinger, folklorist, novelist, humorist, and local liberal activist. Nye clearly never took anything, including himself, too seriously. When, in the midst of the 1960s folk boom, he published a guide to folk songs, he gave it a triply-redundant title that included its own punchline: