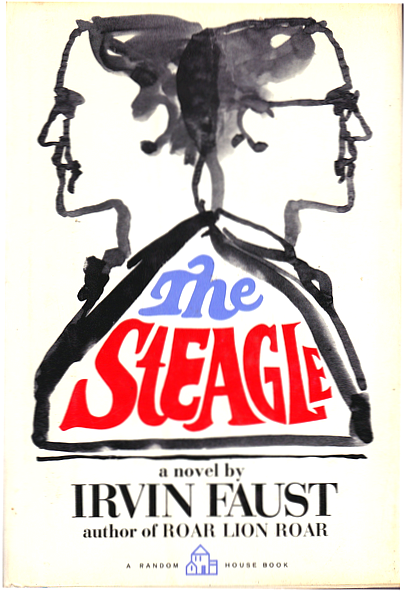

My feelings for The Steagle are a combination of awe and disappointment, sort of like what many felt about Evel Knievel’s attempt to jump the Snake River Canyon in 1974. I admire Irvin Faust’s courage and audacity in trying to write about madness in a way that no one ever had — yet acknowledge that his results failed to hit the target. Somewhere short of the far side of sanity, The Steagle’s drag chute ejects and the book crashes in a messy jumble of words.

If some sharp publisher were to reissue The Steagle today, the book’s cover grab line could be, “A MAD MAN GOES MAD.” For both Faust and his hero, Harold “Hesh” Weissburg, are button-down, sport coat and tie wearing, salarymen of the early 1960s. Five days a week, Faust goes to work as a New York City public school guidance counselor and Weissburg teaches 17th Century English literature to bright-faced undergraduates. They have wives, mortgages, insurance policies, and daily commutes.

Like Don Draper of Mad Men, they’ve been drafted, uniformed, shot at. They’ve also been indoctrinated in American mid-century culture: comic strips and comic books, radio shows and movies, 78 RPM discs and sock hops, sports pages and the streets of Brooklyn. As Jack Ludwig put it in his New York Times review, “Everything is here, as current as Mad Magazine: Billboard America, brand-name America, America the blur seen from the window of a speeding train or car, the plotted-and-pieced America airplane passengers know best.” It’s the same combustible mixture that fueled all of Faust’s work, and all it takes is a spark to set it off.

For Hesh Weissburg, the spark is the news that Russian nuclear missiles have been spotted in Cuba. It triggers a psychotic break that leads him to interrupt his lecture on the mystique of the hero in Elizabethan literature and begin raving about Willie Mays and baseball, descending rapidly from rant to bizarre Brooklyn kid code:

“YOBBOU OBBAND MOBBEE HOBBAVE BOBBEEN COBBONNED, BOBBILKED, SCROBBEWED BOBBYE THOBBEE GROBBEAT SPOBBORTSMOBBEN THOBBAT TOBBOOK OBBOUR CLOBBOSEOBBEST FROBBIENDS FROBBOM OBBUS, OBBAND THOBBEN ROBBEACHED THOBBEE SOBBINOBBISTOBBER FOBBINOBBALOBBITOBBY WOBBITH THOBBEE KOBBIDNOBBAPPOBBING OBBOF THOBBEE GROBBEATOBBEST OBBOF THOBBEM OBBALL HOBBOO OBBOF COBBOURSE OBBIS WOBBILLOBBIE MOBBAYS….”

(which condenses in the more comprehensible “YOU AND ME HAVE BEEN CONNED, BILKED, SCREWED BYE THE GREAT SPORTSMEN THAT TOOK OUR CLOSEST FRIENDS FROM US, AND THEN REACHED THE SINISTER FINALITY WITH THE KIDNAPPING OF THE GREATEST OF THEM ALL WHO OF COURSE IS WILLIE MAYS….”). Leaving his students gaping in bewilderment, he walks out of his class and heads to the airport, grabbing a flight to Chicago (“FLY NOW, PAY LATER!”) that starts a week-long dash about the country in search of….

Well, just what Weissburg is looking for is clear to neither himself nor us. It could be security in a moment of existential anxiety, but it could just as well be something as simple as the certainty of his 14-year-old comics/sports/radio/movie-obsessed self.

Chatting to his seatmate on board the flight to Chicago, Weissburg pretends to be Hal Winter, successful Broadway producer, and in this guise he checks into the Blackhawk Hotel, orders the best steak dinner and French wine in the place, and seduces a beautiful woman before heading off to his next stop. He visits Notre Dame to indulge a fantasy of being the Fifth Horseman in the football team’s legendary 1924 backfield lineup, Milwaukee to relive a romance from his G.I. days.

As he hops from place to place, Weissburg shifts from one fantasy character to another: Bob Hardy, brother to Andy of the movie family; Rocco Salvato, former high-school bully and present gangster; George Guynemer, son of the French flying ace of World War I; Cave Carson, son of doomed spelunker Floyd Collins; and, finally, Humphrey Bogart.

Weissburg heads for ever more artificial versions of the American dream in his manic race to stay one step ahead of the news of possible global annihilation. To Vegas:

Ocean’s Eleven. Sinatra. Judy. Thirty thousand a week. Sun. Desert. Red neon. One-armed bandits. Action. Faites vos jeux. Les jeux sont faits. Nothing Monaco. Nothing Miami. Nothing Reno. Pools. Tanfastic. Bikinis. Action. Vegas.

Finally, when he reaches Hollywood, his mind jumbles together fragments from his cultural and personal memories into a climactic sequence in which he refights World War Two, single-handedly triumphing over all of America’s enemies. I can only convey the verbal cacophony that Faust creates by reproducing two sample pages below.

Like Weissburg’s “OBB” Latin, one can, with patience, decypher this linguistic jumble. Perhaps, in future, scholars will painstakingly extract and identify each of the shards of cultural reference scattered around this ruin. On the other hand, this may be a case where it’s better to take in the effect at a glance and move on.

For the trick in successfully portraying madness in fiction is that the novelist can never fully surrender control to the madmen. Otherwise, language risks becoming word soup. And there’s a lot of word soup in the last pages of The Steagle.

The book had its share of admirers back in the Sixties. Richard Kostelanetz called The Steagle “the most perceptive breakdown in all novelistic literature.” “Of the many new novels I have read in the past three years,” he wrote in TriQuarterly several years after the book’s first publication, it was “the only one that struck me as fusing the three virtues of originality, significance and realization at the highest levels of consistency.”

Jack Ludwig, the Times’s reviewer, felt that it was a mistake to characterize the book as comedy or satire: “It is funny and great in its take-offs. But it is at bottom compassionate, comic and sadly accepting. As long as reality is what it is, fantasy must serve man as refuge.” Time magazine, on the other hand, lost patience with Faust’s verbal fireworks: “This pop novel pops so violently that it cannot safely be perused without welding goggles.”

Faust’s failure didn’t dissuade Paul Sylbert from staging another attempt, however. Five years later, screenwriter and director Paul Sylbert adapted the book for AVCO Embassy Films. Richard Benjamin did his best to capture the mad panache and manic energy of Hesh Weissburg, but there was no way that Sylbert could have caged Faust’s beast into an 87-minute package. It didn’t help that the first-time director was working for legendary director-breaking producer Joseph E. Levine. Working at a time before director’s cuts were invented, Sylbert had to take his frustrations out on the printed page, publishing his account of the disaster, Final Cut: The Making and Breaking of a Film in 1974.

The Steagle, by the way, took its title from an amalgamation that echoes Faust’s zest for cultural integration. The Steagles were a short-lived creation that the National Football League devised during the manpower shortages of World War Two, combining the Philadelphia Eagles and the Pittsburgh Steelers into a single team.