Excerpt

Clallum Jake was a Columbia River Indian by residence, though he was heavier-built and more dignified than river Indians generally were. He lived most of the year on an Indian allotment sand spit that stuck out into the Columbia a few miles above the mouth of the Camas River, where he operated a seining ground during the salmon run, with the help of four or five squaws of varying ages and uniform homeliness. He was a hard-working old buck, and usually hung up from ten to a dozen tons of salmon in a season. He was also a sharp trader. Instead of selling his salmon to the cannery at some starveout price, he preferred to home-dry and peddle it to the upper-country Indians for such raw material as deer hides and the pelts of winter-killed sheep, which his squaws tanned and converted into genuine Indian-beaded buckskin gloves, moccasins, belts and handbags. Knickknacks of that kind found a ready and profitable sale at tourist stores and curio shops around the country, besides supplying the squaws with something to do so they wouldn’t be tempted to start fighting among themselves.

Nobody knew anything precise about the relationship subsisting between Clallum Jake and his squaws. Some public-spirited people in town had tried to find out about it from the squaws a few times, but the squaws knew only a few words of English, all brief and forceful, so the investigation had never got far. Clallum Jake had escaped it himself, being too dignified in appearance to be questioned about his domestic eccentricities by a set of town busybodies who might not have stood up very well under any searching inquiry into theirs. He could understand English moderately well when there was anything in it for him, though he usually professed ignorance of it to be on the safe side. He had no language of his own, or none that anybody could pin him down to, having wandered into the plateau country in the early days from somewhere down on the Coast, where all the native languages were different. In his trading with other Indians, he relied partly on his squaws and partly on a scattering of English mixed with Chinook jargon, the simplified mixture of mispronounced French, Indian, Russian and Eskimo that had once been the universal trade lingo among the western tribes all the way from the Bering Straits to the California line.

One Coast Indian trait that had stayed with him was clumsiness with horses. In spite of the fifty-odd years he had been riding, he still rode like a shirttail full of rocks, but with an air of weighty deliberation that made it look as if he was doing it in fulfillment of some plan too deep and far-ranging to let the general public in on.

Editor’s Comments

Thirty years ago, the University of Chicago Press quietly released a collection of three pieces of short fiction by a retired professor of English, Norman MacLean. Purely through word-of-mouth, A River Runs Through It became a best-seller and nearly won the Pulitzer Prize. More than anything, it was MacLean’s remarkable voice — spare, ironic, experienced but never claiming to be wise, with a soft-spoken good humor — that distinguished the book from anything else published in a good number of years before it. You had the sense that there was nothing the least bit fake in this book — as well as the sense that in waiting so long to tell his stories, MacLean was able (to turn Pascal’s quote around) to make them as short as possible.

I was often reminded of A River Runs Through It while reading Winds of Morning. The two books are set in roughly the same time and place — the Northwestern U.S. in the 1920s. Aside from that, they don’t share much else in common, at least on the surface. The stories are quite different. Winds is a little bit about unraveling the truth behind a murder, more about a young man and an old man herding some horses to a new pasture, and mostly about people and a place in the midst of changing from one era to another. What really reminded me of A River was the voice of Amos Clarke, H.L. Davis’ narrator.

The book is Amos’s recollection, told from a distance of thirty years or so, of one particular experience from his time as a sheriff’s deputy, back when he was barely twenty. Out delivering a summons, he stumbles onto a shooting that looks to be accidental. A ranch hand, Busick, has killed an old Indian, and Amos dutifully takes him into custody. Although it’s an open-and-shut case of manslaughter, Busick gets off — mostly through the collusion of a jury of local businessmen who’d rather have him working and paying off loans that stewing away in prison. Busick gives up his rights to a small patch of grazing land, however, and this sets off the main story in the book.

The sheriff instructs Amos to round up Busick’s horses and lead them up to public pasture with the help on an old man, Hendricks, left to look after them. Hendricks was an early homesteader in the area who built up a healthy estate, but who left under a cloud of rumors after one of his daughters accused him of molesting her. The big story percolating in the background as Amos and Hendricks head north with the horses is the hunt for a murderer. A wealthy rancher married to one of Hendricks’ daughters has been shot dead as he stood in the doorway of his house. In the sheriff’s mind, though, Amos’ job has nothing to do with that.

As it turns out, however, Amos and Hendricks find themselves getting closer, rather than further, from this murder. They stumble across a few threads that Amos’ curiosity and Hendricks’ knowledge of the area and the people in its enable them to follow and, ultimately, solve the case. But this is not the real story in Winds of Morning.

Though horses and wagons are still the main ways of getting around for most people, railroads, cars, and trucks are also regular fixtures. The first wave of homesteaders has receded, leaving a few successful big ranchers and businessmen, more struggling farmers and hired hands, and a lot of abandoned places. Power has shifted, subtly and permanently, from the hands of the rugged individualists like Hendricks to those with money and influence. Although still a wild and beautiful but potentially dangerous land, this West is full of signs that life is changing. Literally, in this passage:

There were some printed signs, mostly faded and weatherbeaten, scattered among the stumps. An old one proclaimed the area to be a part of the Prickettsville municipal water district, and carried a caution against trespassing that didn’t appear to have had much effect, since it was shot full of holes. A newer one from the government printing office stated that the territory thereto adjacent had been stocked with poisoned bait against predatory animals, and advised against permitting sheep does to run loose on it, which, since the buzzards always ate all government poisoned bait and scattered it over half the sheep ranches in the country before the predatory animals got near it, was a way of insuring that there would be enough to go around among the sheep dogs, and they could all poison themselves right at home instead of having to walk miles out into the timber to do it There were smaller signs of varying ages forbidding hunting, fishing, camping, or building fires without a suitable permit, cutting trees or pulling wild flowers, or picking huckleberries except in duly posted and assigned areas and under properly authorized supervision. None of them were supposed to mean anything till summer. They were put up to draw city vacationists, to whom such things gave a pleasantly excited feeling of being the objects of somebody’s attention.

Clarke suspects the change he sees going on aren’t for the better. At one point, he muses:

In old Hendricks’ younger days, there had been more value set on people. Nature had been the enemy then, and people had to stand together against it. Now all its wickedness and menace had been taken away; the thing to be feared now was people, and nature figured mostly as a safe and reassuring refuge against their underhandedness and skullduggery.

But Davis refuses to settle for a simple polemic against progress. This is not the Wild West of good guys versus bad guys, white hats versus black. From the very first scene, it’s clear that Amos is more inclined to try to understand than to judge the people he encounters, and he finds Hendricks shares much the same disposition. “A man can’t tell what’s layin’ around inside of him. There’s too many corners, and things reach out from ’em sometimes that you’d thought was all dead and buried.”

In part, this is because Hendricks is struggling with his own demons. Though innocent of his daughter’s charge of rape, he still took off and lost himself somewhere for a few years before returning to the Columbia River valley. He had his own sin he was trying to escape. One hard winter when most homesteaders were losing whole herds, he had taken up with an Indian squaw for the sole purpose of getting the use of some sheltered pasture, and he kept up the arrangement until he no longer needed the help.

“I couldn’t see how it hurt anybody much,” he tells Amos.

“You can’t tell what will hurt people sometimes,” Amos responds.

“I was out to pile up money in them days,” Hendricks reflects. “Gittin’ ahead in the world was what we called it. nobody ever figured out what they was gittin’ ahead of, I guess. There’s more things than that for a man to git ahead in, anyway. It’s took me a hell of a long time to fin it out….”

Though the pair spend much of the book piecing together the truth about the murder, this is never viewed as a matter of justice or punishment. The culprit, it turns out, is a young Mexican boy traveling with them. His motivation proves to have been his own misguided sense of justice, and they agree to let things rest at that.

“You can’t make up for what you’ve done,” Hendricks tells Amos. “When you do it, it stands against you. You pay for it, no matter what you do afterwards. Good and bad don’t cancel each other out. It don’t lighten a twenty-pound load on one end of a pole to hang twenty-one pounds on the other end. The pole’s got to carry ’em both.”

I hesitate to call this a Western for grown-ups, because that usually just means the sexual element isn’t completely repressed. But Winds of Morning is certainly written from a more mature and morally, economically, even ecologically realistic perspective than just about anything I’ve ever come across that had the label “Western” applied to it. Several dozen characters pass across the stage in the course of the book, and not one gets less than a fully-rounded treatment.

Even the landscape gets a fully-rounded treatment — and what book could qualify as a Western without plenty of landscape:

The river had changed color a little; it was not blackish, as it had been when we looked at it from the hillside, and not roily, as lowland rivers always were after a hard rain, but milky green, like snow water that has thawed too fast for the air to separate from it. The current was swift, but it held to its ordinary level as if the torrents of rain flooding into it had all been beneath its notice.

And, of course, there have to be horses. Amos and Hendricks have both spent their lives caring for, and relying on, their horses. The horses have come to command a certain amount of respect:

It was useless trying to ride the horses down such a place; they had enough work merely to keep their feet under them and keep going, so we dismounted and followed along behind. Halfway down, the slope steepened so we could hardly stand up on it, but the horses by then had discovered how to manage it without wearing themselves out. Instead of trying to walk with the rocks moving and shifting underfoot, they merely started a patch sliding, set back, and coasted on it till it stopped, and then moved on and started another one to coast on. Not many animals are smarter than a range horses, when he is left free to figure things out for himself.

There’s a limit to this respect, though. In fact, we find that horses may have formed a bit too much of Amos’ perspective:

There’s a limit to this respect, though. In fact, we find that horses may have formed a bit too much of Amos’ perspective:

Horses and women. Leave either of them alone with only a man to depend on for company, and they could develop an intelligence so quick and sensitive that it was uncanny to be around. Herd them back with others of their species, and they dropped instantly to a depth of dull pettiness and mental squalor that made a man wonder how he could ever have credited them with intelligence at all….

Personally, I haven’t met many women who’d say that being left alone with a man raises the net IQ. And though Davis tosses a romance in to top Winds of Morning off, it’s the weakness element in the novel, and the most expendable. Men, horses, landscapes, and weather are already enough to make this a rich, intelligent, and thorough enjoyable piece of writing.

A Book-of-the-Month Club selection at the time it was first published, Winds of Morning sold well, but vanished after one paperback run. The Greenwood Press reissued it for academic libraries in 1972 and a small Western press, Comstock Book Distributors, reissued it in hardback in 1996, but these editions are harder to find that the original Morrow release. Fortunately, there are plenty of used copies to be found on Amazon for as little as 99 cents, so there is no excuse for letting this terrific book gather dust. Heck, I’ll even offer to buy your copy if you’re not satisfied after reading it.

Reviews

- • Manas Journal, 13 February 1952:

- Once in a while — once in a very great while we find the temerity to comment upon what is commonly called the “artistic value” of a novel or drama. Having so long championed the view that ideas and ideals are always the Real, and that even the most impassioned recounting of experiences is valueless unless it points a way toward realization of an ideal, a reviewer cannot help but feel a bit of a turncoat if he first stakes out claims for a piece of writing chiefly because he warms to the way it is written. Yet H. L. Davis’ Winds of Morning tempts such extravagance, despite the fact that it is a Book of the Month selection and that BoM reviewers have praised it for much the same reasons.

Davis does have a marked sort of idealism, however, even though it is not addressed to any particular social or psychological problem. It is felt, for instance, in attitudes toward the creatures of nature and the beautiful land which supports them. It is present in the form of compassion and understanding when the subject is crime and criminals, and it emerges most of all in the respect shown for those who are courageously independent. Perhaps good writing always does something of this nature, if it is really good writing, at all.

Winds of Morning is not, in the usual meaning of the word, an “exciting” book. Being so well done it needs none of those emotional injections which often are made to reinforce the efforts of even skillful writers to convey a point of view or an interpretation of experience. Instead, without in the least giving the impression of trying, Mr. Davis helps the reader to feel that each moment of common, everyday life may hold a further awakening of the mind.

- • Time magazine, 7 January 1952

- The story begins with a young deputy sheriff who is sent out to herd an old hoss-wrangler and his strays through the wheat country and into open territory. On the trip, by a series of stumbling inadvertencies, he runs down a murder story and falls in love. He chews over old times and old ways in dozens of small passages of talk with the oldtimer, and with himself. He also takes a deep breath of the wilderness around him, and the reader breathes it with him.

“The noise of a late-lingering flock of wild geese going out to its day’s feeding in the wheat fields woke me the next morning,” Davis may write, with a mildness that is really intensely restrained affection. “The sky was already beginning to fill with light, and there were a few cold yellow sun streaks on the high ridges…”

Such passages give Davis’ prose, and his story too, a quality of imminence—as though at any moment they might break out in crashing event. They never do. The action of the book, though now and again it holds some excitement, has no importance; it rises quietly out of the big land, and sinks quietly back into it. The natural world, in fact, is the only real character in Winds of Morning; the people in the book appear chiefly as traits of that character. Ordinarily, this would be a fatal flaw. The measure of Novelist Davis’ success is that he will almost certainly make a great many readers decide that his favorite country deserves the affectionate priority he gives it.

Find Out More

Locate a Copy

Winds of Morning, by H. L. Davis

New York: William Morrow & Company, 1952

There were seven jars attached to the framework in the centre of the room and as soon as the chief’s sons-in-law had arrived and hung up their cross-bows on the beam over the adventures of Dick Tracy, they were sent off with bamboo containers to the nearest ditch for water. In the meanwhile the seals of mud were removed from the necks of the jars and rice-straw and leaves were forced down inside them over the fermented rice-mash to prevent solid particles from rising when the water was added. The thing began to look serious and Ribo asked the chief, through his interpreter, for the very minimum ceremony to be performed as we had other villages to visit that day. The chief said that he had already understood that, and that was why only seven jars had been provided. It was such a poor affair that he hardly liked to have the gongs beaten to invite the household god’s presence. He hoped that by way of compensation he would be given sufficient notce of a visit next time to enable him to arrange a reception on a proper scale. He would guarantee to lay us all out for twenty-four hours.

There were seven jars attached to the framework in the centre of the room and as soon as the chief’s sons-in-law had arrived and hung up their cross-bows on the beam over the adventures of Dick Tracy, they were sent off with bamboo containers to the nearest ditch for water. In the meanwhile the seals of mud were removed from the necks of the jars and rice-straw and leaves were forced down inside them over the fermented rice-mash to prevent solid particles from rising when the water was added. The thing began to look serious and Ribo asked the chief, through his interpreter, for the very minimum ceremony to be performed as we had other villages to visit that day. The chief said that he had already understood that, and that was why only seven jars had been provided. It was such a poor affair that he hardly liked to have the gongs beaten to invite the household god’s presence. He hoped that by way of compensation he would be given sufficient notce of a visit next time to enable him to arrange a reception on a proper scale. He would guarantee to lay us all out for twenty-four hours.

In

In

There’s a limit to this respect, though. In fact, we find that horses may have formed a bit too much of Amos’ perspective:

There’s a limit to this respect, though. In fact, we find that horses may have formed a bit too much of Amos’ perspective: In his article, “Judging a Book By Its Cover: 12 Book Designers Who Changed the Publishing Industry Forever,” in the May/June 2006 issue of

In his article, “Judging a Book By Its Cover: 12 Book Designers Who Changed the Publishing Industry Forever,” in the May/June 2006 issue of

It was a severe task that lay ahead of me–it was as though I had to perform a grave and spiritual saraband. There were words to be spoken, comprehensible human words, but clearly there was more than just this. Klaus, my frater catholicus, could give absolution, the host and the chrism; he had for his people a language of signs which at one and the same time may not be understood and yet which must be and is understood. But I, here, today? Up there, in my own district, I knew the men condemned to die in the prisons as well as, and frequently much better than, the other men condemned to another sort of death in the hospitals. We had a broad basis on which to build our last hour together, and there was never need to try to start at the last moment. Here I must begin from almost nothing. For, strictly speaking, I should not admit that I knew what I had read in the documents. Otherwise he might well say to himself that the pastor had been spying on him, and had come here with the intention of putting something across. I could imagine him saying: “No thanks. No rubbish for me from your piety junk shop.”

It was a severe task that lay ahead of me–it was as though I had to perform a grave and spiritual saraband. There were words to be spoken, comprehensible human words, but clearly there was more than just this. Klaus, my frater catholicus, could give absolution, the host and the chrism; he had for his people a language of signs which at one and the same time may not be understood and yet which must be and is understood. But I, here, today? Up there, in my own district, I knew the men condemned to die in the prisons as well as, and frequently much better than, the other men condemned to another sort of death in the hospitals. We had a broad basis on which to build our last hour together, and there was never need to try to start at the last moment. Here I must begin from almost nothing. For, strictly speaking, I should not admit that I knew what I had read in the documents. Otherwise he might well say to himself that the pastor had been spying on him, and had come here with the intention of putting something across. I could imagine him saying: “No thanks. No rubbish for me from your piety junk shop.”

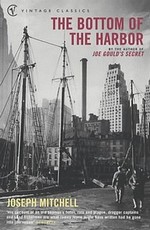

“Mitchell [was] a North Carolinian who became a New Yorker. He went straight from the University of North Carolina to a New York newspaper [The New York Herald Tribune–ed.]. First a reporter, he quickly turned into a feature writer, and then he became an essayist, the best in the city. [He joined the staff of

“Mitchell [was] a North Carolinian who became a New Yorker. He went straight from the University of North Carolina to a New York newspaper [The New York Herald Tribune–ed.]. First a reporter, he quickly turned into a feature writer, and then he became an essayist, the best in the city. [He joined the staff of  The other five are a kind of writing for which there is no name. Each tells a story, and is dramatic; each is both wildly funny and so sad you can hardly bear it; each tells its story so much in the words of its characters that it feels like a kind of apotheosis of oral history. Finally, like the Icelandic sagas, each combines a fierce joy in the physicality of living with a stoical awareness that all things physical end in death, usually preceded by years of diminishment. One winds up admiring Mitchell’s characters (all real people), loving them, all but weeping for them, maybe hoping to live as gallantly.

The other five are a kind of writing for which there is no name. Each tells a story, and is dramatic; each is both wildly funny and so sad you can hardly bear it; each tells its story so much in the words of its characters that it feels like a kind of apotheosis of oral history. Finally, like the Icelandic sagas, each combines a fierce joy in the physicality of living with a stoical awareness that all things physical end in death, usually preceded by years of diminishment. One winds up admiring Mitchell’s characters (all real people), loving them, all but weeping for them, maybe hoping to live as gallantly.