David Forrest was the pen-name of Australian writer, academic and historian David Denholm (1924-1997). Among his numerous works of non-fiction, including an acclaimed history, The Colonial Australians about the early white settlement of the country, were a few novels. The Last Blue Sea, published in 1959, was his first. The book drew considerably praise and attention when released in Australia and the US. However, the novel went out of print by the early 1970s and was then largely forgotten. Penguin Books Australia published a reprint in

David Forrest was the pen-name of Australian writer, academic and historian David Denholm (1924-1997). Among his numerous works of non-fiction, including an acclaimed history, The Colonial Australians about the early white settlement of the country, were a few novels. The Last Blue Sea, published in 1959, was his first. The book drew considerably praise and attention when released in Australia and the US. However, the novel went out of print by the early 1970s and was then largely forgotten. Penguin Books Australia published a reprint in

1985 but the book has remained off the shelves since.

Forrest, a veteran himself of WW2, fought with the 59th Battalion of the Australian Army in New Guinea in 1943. That unit, although it had fought as a regular formation in the First World War, had been down-graded to a part-time reservist (militia) unit during the inter-war years. When the Second World War began, the 59th was re-assembled as a militia force. During the war, such militia units, comprised of conscripts and a smaller number of part-time reservists, formed a large part of the Australian army after 1942.

During the war, there was considerable animosity between the militia units and the men of the AIF (Australian Imperial Force), the latter comprising the volunteers who enlisted in the early part of the war. With some justification, the AIF units regarded themselves as better-trained, more professional and more motivated than the Militia men, whom the former nick-named “Chockos” i.e., chocolate soldiers who always melted under fire. There was no doubt that some militia formations deserved their poor reputations, especially those that remained garrisoned in Australia and were rife with in-discipline, desertions and poor morale. Yet some militia units performed remarkably well in the New Guinea Campaign, most famously at Kokoda in 1942. One can say “remarkably” considering the often poor training, lack of equipment and indifferent leadership many militia units were burdened with (some men arrived in New Guinea literally never having fired a rifle before).

With this background in mind, Forrest’s novel depicts a Militia unit—the 83rd battalion—in the campaign in eastern New Guinea in 1943 as US and Australian forces advance northwards, slowly pushing back the Japanese. The story is told from the viewpoints of a number of characters, including the battalion’s senior officers. But the primary focus is on one platoon and, in particular, on one of its’ sections comprising a Corporal and eight privates.

If the novel has any main characters, they would be two privates, 19-year-old Ron Fisher, a Bren-gunner and 26-year-old Robert “the Admiral” Nelson, a former schoolteacher and now an Owen (Australian-made sub-machine-gun) gunner. Nelson, the oldest of the section, has the fatherly role of the group. Yet even he, with his worldly wisdom, appears in awe of Fisher, an enigmatic figure, mature far beyond his years and whose background is only hinted at but indicates that he survived a tough childhood and is now a man that understands life more than many men twice his age.

The platoon engages the Japanese in the steaming, thickly forested steep slopes of New Guinea. The enemy, under-supplied and starving, fight desperately and with suicidal courage. In this struggle, there is no quarter, the enemy is never examined close-up, he remains a distant, hated figure. The militia men have to endure the taunts and insults from their AIF cousins. As the platoon advances through a ruined town, watching them are some AIF commandoes who snort with contempt “any battle they start, we have to finish.” The army is on a race against time, not just against the enemy but against the jungle and its climate. The campaign must be won before too many men succumb to malaria and before their rotting uniforms literally fall from their bodies.

The potential weaknesses of the militia is personified in one soldier of the section, private “Nervous” Lincoln who deserts early in the campaign but is caught and returned to his unit. He nearly makes it through to the very end of the advance before succumbing to his fear. To modern eyes, this might redeem him but as far as his comrades are concerned, “they would remember all their lives that Lincoln was not with them.” A major theme of the novel is the meaning to human existence that can be discovered by the endurance of hardship and danger. The Pacific Ocean (the “last blue sea” of the title) becomes a symbol as it slowly, tantalisingly becomes nearer as the exhausted soldiers advance through the jungle against the surviving enemy. A symbol of promise, of peace, of a just reward for hardship, sacrifice and duty. As the novel progresses, it becomes apparent that faint-hearted types like Lincoln were the exception, not the rule. “Their uniforms were rotting and falling apart, but their weapons were spotlessly clean.”

The novel explores the inner musings of the characters. In this, it anticipates such a device employed in the 1998 war movie The Thin Red Line although Forrest’s novel is not as dreamily lyrical as that film. Like all war novels published prior to the 1970s, there is a curious lack of coarse language, a reflection of the need to satisfy censors of the day. One critic did suggest that the novel’s depiction of Australian soldiers lacked the cheeky humour that they were known for, saying the Aussies in this novel are “way too serious and philosophical” in their manner. That might be unfair, given that these half-trained soldiers had been sent to one of the harshest terrains of the war against one of the most fanatical enemies, so a sombre mood might be understandable. In one later scene, Nelson, now a walking wounded case, is sent back to the rear accompanied by a younger injured soldier. The two crippled men have to climb a forested mountain, through clinging mud and steaming rain, their wounds crawling with infection. Seeing that the younger man’s will and strength is failing, Nelson saves him by goading him, “Didn’t you have to fight for anything, Jonesy? Was life just dished out to you on a silver plate?”

In another scene during the long trek back, Nelson says to Jones, “You can make this mountain mean something. I climbed a mountain once. When I was your age. And then I wasted the next seven years. You see, I should have gone on and climbed the next mountain. Only when I was over the first one, I sat down. I had to come to New Guinea to wake up to myself ….”

The Last Blue Sea remains curiously little-known in Australia, despite the lavish attention bestowed on this nation’s military history. It is one Australian novel that deserves a fresh audience.

Wilson, an English academic who had already worked with refugees from the First World War, Russia, and the Spanish Civil War, joined the

Wilson, an English academic who had already worked with refugees from the First World War, Russia, and the Spanish Civil War, joined the  In 1945,

In 1945,

Of course, the Germans didn’t attack the French and British in April 1940, but two months later, in June, and when they did, they wisely bypassed the Maginot Line in favor of a blitzkrieg through the Ardennes and the Lowlands. This is a major reason why

Of course, the Germans didn’t attack the French and British in April 1940, but two months later, in June, and when they did, they wisely bypassed the Maginot Line in favor of a blitzkrieg through the Ardennes and the Lowlands. This is a major reason why

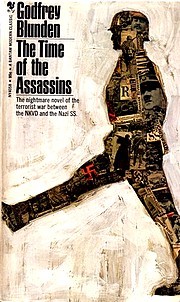

I first read Godfrey Blunden’s

I first read Godfrey Blunden’s

If history is a broom, sweeping back and forth through time, then

If history is a broom, sweeping back and forth through time, then