Excerpt

David watched the door close: gently, smoothly, as though drawn by a magnet, the steel door drew closer to its steel frame. Finally they became one.

High up, behind a rectangular metal grating in the wall, David saw something stir. It looked like a grey rat, but he realized it was a fan beginning to turn. He sensed a faint, rather sweet smell.

The shuffling quietened down; all you could hear were occasional screams, groans and barely audible words. Speech was no longer of any use to people, nor was action; action is directed towards the future and there no longer was any future. When David moved his head and neck, it didn’t make Sofya Levinson want to turn and see what he was looking at.

Her eyes–which had read Homer, Izvestia, Huckleberry Finn and Mayne Reid, that had looked at good people and bad people, that had seen the geese in the green meadows of Kursk, the stars above the observatory at Pulkovo, the glitter of surgical steel, the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, tomatoes and turnips in the bins at market, the blue water of Issyk-Kul–her eyes were no longer of any use to her. If someone had blinded her, she would have felt no sense of loss.

She was still breathing, but breathing was hard work and she was running out of strength. The bells ringing in her head became deafening; she wanted to concentrate on one last thought, but was unable to articulate this thought. She stood there–mute, blind, her eyes still open.

The boy’s movements filled her with pity. Her feelings towards him were so simple that she no longer needed words and eyes. The half-dead boy was still breathing, but the air he took in only drove life away. He could see people settling onto the ground; he could see mouths that were toothless and mouths with white teeth and gold teeth; he could see a thing stream of blood flowing from a nostril. He could see eyes peering through the glass; Roze’s inquisitive eyes had momentarily met David’s. He still needed his voice–he would have asked Aunt Sonya about those wolf-like eyes. He still even needed thought. He had taken only a few steps in the world. He had seen the prints of children’s bare heels on hot, dusty earth, his mother lived in Moscow, the moon looked down and people’s eyes looked up at it from below, a teapot without its head, where there was milk in the morning and frogs he could get to dance by holding their front feet–this world still preoccupied him.

All this time David was being clasped by strong warm hands. He didn’t feel his eyes go dark, his heart become empty, his mind grow dull and blind. He had been killed; he longer existed.

Sofya Levinton felt the boy’s body subside in her hands. Once again she had falled behind him. In mine-shafts where the air becomes poisoned, it is always the little creatures, the bird and mice, that die first. This boy, with his slight, bird-like body, had left before her.

“I’ve become a mother,” she thought.

That was her last thought.

Her heart, though, still had life in it; it still beat, still ached, still felt pity for the dead and the living. Sofya Levinton felt a wave of nausea. She was hugging David to her life a doll. Now she too was dead, she too was a doll.

Comments

If War and Peace had never been written, it might have been easier for Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate to win an audience. To compare Life with War is so obvious and instinctive it’s almost an autonomic reflex. They’re both big, thick novels about Russia at war with enormous casts of characters, real and fictional.

The comparison does Life and Fate a disservice on two counts. First, any reader put off by the bulk or subject of War and Peace would hardly think twice of giving Life and Fate a try. And second, although Life is a superb novel, it is not quite on the level of what is arguably one of the pinnacles of the novel as an art form.

Still, the comparison is inescapable. Like War and Peace, Life and Fate is a tapestry, with numerous narrative threads, many of them dealing with members of an extended family: Alexandra Shaposhnikova, her three daughters–Lyudmila, Yevgenia, and Marusya–and her son Dmitry. There is Viktor Shtrum, Lyudmila’s second husband, is an ambitious physicist who encounters an early version the post-war campaign against Jewish intellecturals but is saved by Stalin’s deus ex machina intervention. Yevgenia struggles with the deprivations of home front life, falls in love with a maverick Army officer who leads a crucial tank assault at Stalingrad, and puts herself at risk by sending a parcel to her ex-husband, a commissar fallen from favor, in Lyubyanka Prison. Dmitry’s son Seryozha fights in the ruins of Stalingrad, part of a small group of soldiers isolated and holding out in house 6/1.

But the cast ranges far wider than just the Shaposhnikovs. Stalin, General Paulus, the German commander at Stalingrad, and Adolf Eichmann all make appearances. Robert Chandler’s excellent English translation provides a seven-page list of characters at the end of the book. The categories alone give an indication of the scope and diversity of Life and Fate:

- The Shaposhnikov Family and Their Circle

- Viktor’s colleagues

- Viktor’s circle in Kazan

- In the German concentration camp

- In the Russian labour camp

- On the journey to the gas chamber

- In the Lubyanka prison

- In Kuibyshev

- At Stalingrad power station

- Getmanov’s circle in Ufa

- Members of a Fighter Squadron of the Russian Air Force

- Novikov’s Tank corps

- Officers of the Soviet Army in Stalingrad

- Soldiers in House 6/1

- In the Kalmyk Steppe

- Officers of the German Army in Stalingrad

Despite this scale, the action in this novel is on a small, intimate level. A young girl fantasizes about her lover. The tank commander, Novikov, removed from his post for diverting ever so slightly from the official plan, waits in a room to be questioned and probably beaten. Viktor Shtrum bickers with his wife and agonises over minor incidents of office politics. Lyudmila fights to make her way by tram to see her wounded son. Krymov, the commissar, listens to his interrogator chat on the phone about cottage cheese and a dinner invitation “as though the creature sitting next to the investigator were not a man, but some quadruped.”

Grossman’s capacity for getting inside the minds of his characters is not limited to the Russians:

… The brain of the forty-year-old accountant, Naum Rozenberg, was still engaged in its usual work. He was walking down the road and counting: 110 the day before yesterday, 61 today, 612 during the five days before–altogether that made 783 … A pity he hadn’t kept separate totals for men, women and children … Women burn more easily. An experienced brenner arranges the bodies so that the bony old men who make a lot of ash are lying next to the women. Any minute now they’d be ordered to turn off the road; these people–the people they’d been digging up from pits and dragging out with great hooks on the end of ropes–had received the same order only a year ago. An experienced brenner could look at a mound and immediately estimate how many bodies there were inside–50, 100, 200, 600, 1000 … Scharfuhrer Elf insisted that the bodies should be referred to as items–100 items, 200 items–but Rozenberg called them people: a man who had been killed, a child who had been put to death, an old man who had been put to death. He used these words only to himself–otherwise the Scharfuhrer would have emptied nine grams of metal into him….

One of the most moving of these small stories is that of Anna Semyonova, Viktor’s mother, who, like Grossman’s own mother, is trapped in the town of Berdichev with thousands of other Jews when the Germans sweep through the Ukraine. Grossman’s mother was shot and buried in a mass grave outside the town. After months of captivity in a ghetto, Anna is packed onto a cattle car and transported to Auschwitz. Along the way, she befriends an orphaned boy, David, and, in the excerpt above, they are herded into the chambers and gassed.

Before leaving the ghetto, however, she composes a letter to Viktor, knowing she will never see him again:

They say that children are our own future, but how can one say that of these children? They aren’t going to become musicians, cobblers or tailors. Last night I saw very clearly how this whole noisy world of bearded, anxious fathers and querulous grandmothers who bak honey-cakes and goose-necks–this whole world of marriage customs, proverbial sayings and Sabbaths will disappear forever under the earth. After the war life will begin to stir once again, but we won’t be here, we will have vanished–just as the Aztecs once vanished.

This letter is easily one of the finest works in the literature of the Holocaust. The filmmaker Frederic Wiseman was so affected by this chapter that he adapted it into a play, “Last Letter,” which he filmed in 2003.

Life and Fate also reflects Grossman’s own development, his disillusionment with the Soviet state and his acceptance of his Jewish roots. Born in Berdichev in 1905, Grossman was raised as a secular Russian. Educated as a chemist, he started writing while still attending Moscow State University. After working for a few years in the Donbass mining region, he switched professions.

By the time Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Grossman was a member of the Writer’s Union and a popular journalist. He spent much of the war as a frontline reporter for the Red Army newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda, including during the battle for Stalingrad, which forms the centerpiece of Life and Fate. He also witnessed the liberation of Treblinka and other concentration camps, and wrote some of the earliest coverage of the extermination of the Jews to be published anywhere.

The strength of Life and Fate’s depiction of combat, destruction, and its effects on soldiers and civilians stems directly from his wartime reporting, which has been collected and published in A Writer at War. The collection was edited by Luba Vinogradova and Anthony Beevor, who openly acknowledges his debt to Grossman for much of the descriptive power of his own account of the battle, Stalingrad.

During the war, Grossman wrote a great deal of propagandist material proclaiming the victory of the liberating Soviet state over the fascist Germans. In the novel The People Immortal, a realistic account of the demoralisation and panic of Soviet troops before the onslaught of the Wermacht in 1941 turns into a socialist fantasy in which a heroic commissar organises a successful counter-attack that routs the enemy. The Germans, “accustomed to victory for seven hundred days, could not and would not understand that on this seven hundred and first day defeat had come to them.” The soldiers celebrate not only their victory, but also the courage and leadership of their commissar: “The Commissar was in front, the Commissar was with us!”

In fact, Grossman’s loss of idealism began before that, starting with the mistaken arrest of his wife, Olga Guber, during the purges of 1937-1938. In Life and Fate, the war is portrayed as a contest between two equally ruthless states, two forms of totalitarianism differing only in ideology and technique. What heroism there was to be found was only as isolated, individual acts.

In the latter stages of the war, Grossman, Ilya Ehrenburg, and others compiled documentation of the Nazi persecution of the Jews–and instances of Jewish resistance–in The Black Book. The Soviet authorities refused to publish it, however, and Grossman watched Stalin turn to persecuting Jews himself in the late 1940s.

Grossman condensed many of these experiences into Life and Fate, which he worked on through much of the 1950s. The purges, the persecution of Jewish scientists and engineers, the Holocaust, the battles, Stalin’s manipulation of all aspects of Soviet life all come to play in the novel. It developed into a very unfavorable and unapologetic account of the state’s power and corruption. It was all too realistic to pass as socialist realism. When Grossman submitted the novel for publication, a Politburo member told him it was unpublishable and would remain so for the next 200 years. As Vladimir Voinovich later pointed out, the most telling part of that remark was the certainty that the book’s merit would easily survive that long.

Grossman died without seeing Life and Fate in print–believing, in fact, that every copy in existence had been confiscated. Fortunately, his friend, the poet Semyon Lipkin, was able to photograph the manuscript, and passed a copy to Andrei Sakharov, who in turn provided it to Voinovich, who smuggled it to Switzerland in 1980.

Although the book was highly praised when first released, its bulk and grim subject put most potential readers off, and it soon passed out of print. Harvill Press reissued it in 1985 and 2003, and New York Review Books announced it would be released as part of its Classics series in May 2006.

Find Out More

Locate a Copy

Life and Fate, by Vasily Grossman, translated by Robert Chandler

New York: Harper and Row, 1980

The barber at Stadelheim prison is called Adam, and most people don’t know if it his given name or his surname. He is not an independent businessman, but a state employee with the title of Surgical Assistant and a certificate attesting to his competence. He lives in the prison. Until 1935 he lived in the same capacity in the surgical clinic, and shaved the hairy parts of bodies before they were submitted to the surgeon’s knife. He is a master of his trade, but his trade has nothing in common with the gay, loquacious beautification work of a Figaro. For he does not shave faces. Adam is grave and taciturn and emaciated like a fakir. His office, his appearance and the late hour of the night at which he usually goes into action, spread terror, deadly terror. He is used to it and pays no attention to it. Sometimes it happens that his clients must be tied to their cots face down and cut hair in any position and has never yet nicked anyone. That is his pride.

The barber at Stadelheim prison is called Adam, and most people don’t know if it his given name or his surname. He is not an independent businessman, but a state employee with the title of Surgical Assistant and a certificate attesting to his competence. He lives in the prison. Until 1935 he lived in the same capacity in the surgical clinic, and shaved the hairy parts of bodies before they were submitted to the surgeon’s knife. He is a master of his trade, but his trade has nothing in common with the gay, loquacious beautification work of a Figaro. For he does not shave faces. Adam is grave and taciturn and emaciated like a fakir. His office, his appearance and the late hour of the night at which he usually goes into action, spread terror, deadly terror. He is used to it and pays no attention to it. Sometimes it happens that his clients must be tied to their cots face down and cut hair in any position and has never yet nicked anyone. That is his pride.

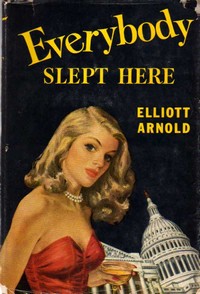

Elliott Arnold’s

Elliott Arnold’s  Many of the characters Arnold sketches are one-dimensional and forgettable, but he does a marvelous job with Willy and his wife. Willy wears a girdle to rein in his gut and relaxes by sewing women’s’ dresses, and serves his time in uniform finding the best Scotch, the finest steaks, and whatever other amenities the Congressmen and generals need. It would be easy to make him preposterous and contemptible. Instead, Arnold is able take us past first impressions and show that he is also an honorable man in his own way, and a tender husband to his fragile wife.

Many of the characters Arnold sketches are one-dimensional and forgettable, but he does a marvelous job with Willy and his wife. Willy wears a girdle to rein in his gut and relaxes by sewing women’s’ dresses, and serves his time in uniform finding the best Scotch, the finest steaks, and whatever other amenities the Congressmen and generals need. It would be easy to make him preposterous and contemptible. Instead, Arnold is able take us past first impressions and show that he is also an honorable man in his own way, and a tender husband to his fragile wife.