Charlotte Herz is not a model human being. She has no patience for people she disagrees with and no qualms about telling them so. She has an affair with the husband of a kindly Englishwoman who hires her to care for her children. She chooses not to have an abortion when one is offered and then abandons the child on a train and flees.

And yet, through the almost 400 pages of Makeshift she is a riveting narrator. We meet her in a nursing home in New Zealand, recovering from … well, as we only learn many chapters later, the measles. She is anxious to leave. For one thing, she hasn’t much money. She suspects her genial doctor of padding her bill: “To Miss Charlotte Herz for Professional Services, 20 guineas: for Professional Smile, 10 guineas.”

She is bored and irritated with the bland pleasantness of New Zealanders, their country, and their ceilings. For weeks, she lay flat on her back, staring up:

This nursing home is far too efficient to have ceilings with any incident in them: there are no interesting cracks that could be imagined into men’s faces, no damp marks the mind could conjure into little cats. Simply a high remote acre or so of impeccable whitewash, faintly changing with the faintly changeful sky.

Improved, she can now sit outside in the sunshine, “eyes goggling downwards” at the perfect green lawn, “a happy picture of convalescence.” And so, she decides, she must write. She has a great deal of anger and hatred to get out of her system: “I cannot forever struggle with myself, forever gnaw serpent-like at my own tail, nor swallow my own venom.”

How she came to be in New Zealand and how she came to harbor such venomous thoughts and emotions is the story she tells. It starts in Berlin, just after the end of the First World War, “in that brief Indian summer after the war; that little time, between the occupation and the inflation, when we in Germany had hope.” A very little time.

Within months, Charlotte and her sister are huddled under their father’s old ulster coat in an unheated room they rent from a bitter anti-Semitic landlady. Having grown up in a prosperous bourgeois family, Charlotte and Mitzi are now near the bottom of Germany’s new postwar food chain: orphans, near-penniless, lacking any employable skills — and Jewish. Before the Kaiser’s empire collapsed, they would have considered themselves assimilated: secular, never setting foot in a synagogue, unfamiliar with Jewish rites and rituals aside from an occasional funeral.

But even before Hitler is a name seen in the Berlin papers, being Jewish is enough reason to be kicked a rung or two down the social ladder. “Whether we like it or not,” in this Germany, “we are nothing less than Jew.” The only way for the sisters to climb back up is simple: marry into wealth. Mitzi meets a dull but adoring American, son of an industrialist, marries, and is soon off to the safety of Pennsylvania.

Charlotte, however, is a creature of her own mind and heart. Her Tante Clara, one of the few relatives still with a little money, offers her a room. But it’s strictly a business proposition: “I was to marry something rich as soon as possible.”

Instead, she falls in love with her charming cousin, Kurt, and one hot afternoon in the tall grass of the Grunewald, gives herself to him. Unfortunately, where Charlotte is a romantic, Kurt is a realist. She heads to the Alps for a holiday, courtesy of American dollars from Mitzi; he marries an heiress.

One thing I found fascinating about Makeshift was how effectively Sarah Campion depicts a world in which women almost — but not quite — had an independent life within their grasp:

Even now, as I waddled swollen between the parting Grübl grasses, I was blazing a new brave trail for womanhood, for single women: establishing the right of even’ woman to motherhood without any of the boredoms of marriage. After all, why not? If men were sexual free-lances, why not women? It all seemed so simple, so gloriously obvious.

Once she gives birth, however, Charlotte makes a much grimmer estimate of her future. “Life in Germany for a battling spinster was even then hard enough: what should I do with a child?” Her only hope would be to find a man dumb or conniving enough to accept a single woman with an illegitimate child:

After that, a married life begun on shame, continued in boredom and stuffy closeness, made up of lustful unloving nights, nagging days, brats begotten in pure animal fury coming year after year to be suckled, clothed, washed, endured—all on a foundation of my shame and my rescuer’s brief nobility simmering down to a reminder of my shame. He would unendingly want gratitude. I hated gratitude then, I hate it still.

If she rejects this choice, she knows she will soon run out of what little money she has and have nothing: “Nothing is a ghastly word, even more devastating in German than in English.” So, she takes the one other choice open to her, the one terrible choice always open to desperate people. She runs away. She steps off the train taking her back to Berlin and leaves her baby daughter behind.

Makeshift is a remarkable account of the choices one Jewish woman makes to survive in a hostile world. After a favorite uncle is fatally injured by a group of SS thugs, she flees Germany for England. There, she is taken in by the Flowers, distant relatives living in a comically comfortable cocoon:

After four square meals, and any number of such unconsidered trifles as elevenses with cream cakes, cocktails before dinner and Horlicks at 11 p.m. to fend off the alleged horrors of night starvation, any Flower could go to its bed, bury its nose in the pillow as soft as a swan’s breast, and sleep like a log. In case by any dirty chance sleep were for a while denied, each Flower had by its bed a little table bearing reading-lamp, the latest worthless fiction, and a chintz-covered box brimming with digestive biscuits.

(Ah, to be a Flower!) But at heart, the Flowers are as mercantile in their thinking as Tante Clara. It’s lovely having Charlotte for a visit, but she needs to sort this business of getting a husband, and quickly.

Charlotte ultimately arrives in New Zealand via South Africa and Australia, but it’s a route we can recognize from Goldilocks and the Three Bears. At each stop, Charlotte tries out a new bed and then rejects it. Should she marry a stolid Cape Town farmer and resign herself to “a little folding of the hands to sleep, to the good, earthy sleep of the intellect women enjoy in that fruitful land?” Should she marry Harry, the congenial, adoring older man she meets on the boat to Sydney? Not after he has a near-fatal hemorrhage and becomes an invalid.

Having bounced from uncomfortable bed to uncomfortable bed, Charlotte comes to a conclusion both utterly selfish and utterly pragmatic: that she is a woman “who now was no longer in love with anything but her own comfort, her own assured future.” Years after she rejected the advice of Tante Clara and the Flowers, she recognizes the ugly, essential necessity of choosing survival over self-actualization.

Though the only scene of overt brutality against Jews is Onkel Hans’s beating by a few young SS men, still a year or two before Hitler comes to power, though the war is still a year or two from breaking out as Charlotte sits in the peaceful garden of her nursing home, Makeshift is a Holocaust novel. One of the more unusual Holocaust novels, perhaps, written before Auschwitz had been built, before scenes of Buchenwald had been displayed in newsreels around the world, but still a story about how one survives when homeless, unwanted — and fully conscious of the threat hovering just over the horizon:

While the spectators sit around in a sodden mass, no more than mildly uneasy, the bull is slaughtered in the ring, the blood flows, the torn flank gapes, the entrails drop sluggishly. In Wolfenbiittel the maddened Jew rushes upon barbed wire, away, away, anything to get away, and hangs there, a screaming bloody mass, till there is no more noise. In Berlin there is a pogrom to avenge the death of one man killed by a youth as mad as Hitler but more obscure. So once more, in Berlin, blood flows from the Jews. The smell of blood—oh, my God, the smell of blood!—once more fills the air.

“Comfy?” the man Charlotte has decided she will marry asks her immediately after this passage.

No, Charlotte knows she will never really be comfy.

Makeshift is a work that synthesizes experience and imagination. Born Mary Coulton, the daughter of Cambridge historian G. G. Coulton, Sarah Campion (her pen name) attended a teacher training college, and after graduating with honors, spent years traveling around Europe until she landed in Berlin in 1933. There she taught English and came to know families like the Herzes. In fact, she left Germany 1937 when she was being pressured to identify her Jewish students to the Nazi authorities.

Like Charlotte, she spent time in South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand, but in her case, she was vocal and overt in her political and social views, establishing a lifelong commitment to activism, and returned to England around the start of the war. She married New Zealand writer Antony Alpers and the couple eventually settled in Auckland. Though they divorced, she remained in New Zealand, where she continued to organize in support of liberal causes. Alpers/Campion must have been a woman with superpowers of empathy, a capacity for getting inside another human’s skin: the source, perhaps, of the imaginative energy that radiates throughout this book.

Incredibly, most of her fiction was written during the years in which she was traveling and working abroad. Makeshift was her sixth novel; she wrote six more between 1940 and 1951. Even more amazingly, she managed to write three novels set in rural Australia, including Mo Burdekin, her only book to have been reissued to date, despite spending less than a year in the country. In fact, she is still occasionally referred to as an Australian writer.

Much of Campion’s work has become extremely hard to find. Worldwide, there are just 19 copies of Makeshift available in libraries worldwide, according to WorldCat.org. Fortunately, the book is available electronically on Internet Archive. I highly recommend it. In Charlotte Herz, Sarah Campion creates a narrator whose intelligence, humor, and ruthless honesty — about herself more than anyone — makes for a thoroughly rewarding reading experience. Definitely my favorite book of the year so far.

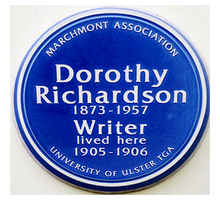

Almost two years ago, I embarked upon my most ambitious and, it turned out, most rewarding reading task, working through the thirteen books of Dorothy Richardson’s

Almost two years ago, I embarked upon my most ambitious and, it turned out, most rewarding reading task, working through the thirteen books of Dorothy Richardson’s