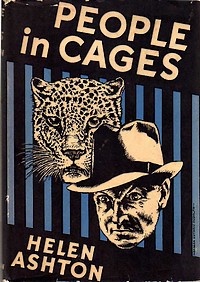

Its cover (at least of the U. S. edition) may be the best thing about Helen Ashton’s 1937 novel, People in Cages. Ashton, a fine writer who can well be included with other “middlebrows” featured on Lesley Hall’s site, must have approached People in Cages

as a set-piece, as its design is as intricate as the mechanisms of a watch.

The novel takes place within the space of a few hours on a hot July afternoon in London. Fate, family outings, and pure coincidence bring together a cast of characters within the confines of the London Zoo. Each person is linked to at least of few of the others, to the point that one almost needs a link analysis tool to keep track of them all. To give you a taste of this world where no one seems more than one degree of separation from anyone else, there are:

- • John Canning

- A former Army officer now wanted for some kind of business fraud and the brother of

- • Mary Canning

- Secretary to Dr. James Grayson, today accompanying

- • Laura Grayson

- Wife of Dr. Grayson, John Canning’s lover, and sister to

- • Bunty MacIlroy

- Socialite and gad-about engaged to

- • Dennis Elliott

- Arctic explorer and son of

- • Colonel Elliott

- John Canning’s former army commander and husband of

- • Mrs. Elliott

- who is being treated by Dr. Grayson for breast cancer.

Once Ashton herds her cast into the zoo, we trail along with one, then another, as they weave in and out of the exhibits, meeting or not meeting, sighting or being oblivious of each other. The narrative tension gradually builds as the police, unknown to Canning, gather and close upon him. And, at regular intervals, Ashton notes the parallels between the circumstances of the people at the zoo and the animals they are watching:

Through this rabble of vulgar and domestic pleasure-seekers the fugitive made his way, looking about him with his bold and shifty stare, thinking them all plain, shabby, harassed and undersized, resenting it when they pushed against him like wandering cattle, not looking where they were going; it seemed to him suddenly intolerable that he should be driven out of the comfortable world that he knew by the prejudice and stupidity of the herd about him….

“… I’ve turned her into a dried-up discontented creature, hungry and barren….”

“Laura is like a young golden lioness in a cage, vain, spoilt, nervous, afraid of her natural duties–and I’m like an old lioness, shut up behind bars, away from my kind, without a chance to breed, because the world is overstocked with us and the menagerie can’t afford another litter.”

… There was something wild and sullen about all these nocturnal creatures, thought the young policeman complacently; the cages were like a row of prison cells and the animals were like sentenced thieves and criminals….

“I don’t think we’ve any right to stand and laugh at them, just because they’re shut up and because they behave like human beings. We’re all in cages ourselves and some of our own performances must be very amusing to God.”

Unfortunately, Ashton’s theme of man as wild, trapped beast is undermined by the mechanical precision of her approach. She weaves her characters’ paths and thoughts together so intricately that the contrast between theme and structure is too stark and the reader soon starts spotting all the joints and hinges. In this zoo, no one idly glances at a stranger. If a policeman notices the “savage and startled gleam” in the eyes of a well-dressed man in front of the dingo cage, it has to be John Canning, of course. If another remarks upon a woman’s “brown and white leaf-patterned gown,” they will turn out to be former sisters-in-law. It’s all so airtight that it’s amazing any life manages to leak through.

Ashton would have been better served by chucking the choreography and letting her characters take the lead. As a creator of interior monologues, she skillfully manages to be true to class, gender, age, and circumstance, and to hop her way through nearly two dozen minds without missing a step. It may be that Ashton felt her readers needed to be guided through this web of interior monologues by a particularly obvious structure. Ashton’s novels were consistent best-sellers, and the expectations of readers for no surprises (“More, but just like the last one”) is a curse of best-selling writers.

In any case, despite my misgivings about People in Cages, I intend to give Ashton’s best-known novel, Doctor Serocold

, a try. The admirable Persephone Books has also reissued Ashton’s 1932 novel, Bricks and Mortar

.

People in Cages earned Ashton and her publisher a libel charge, by the way. E. M. Forster discussed the case on one of his BBC radio broadcasts, and it’s worth quoting here to illustrate (a) how ridiculously broad the English libel law of the time were and (b) how thin-skinned some people can be:

I’m glad to say that this year a libel action was brought that failed. It was over a novel called People in Cages

. There was a villian in the novel and he got arrested in the zoo, and the authoress, Miss Helen Ashton made great efforts not to give the villain the name of any living person. But unfortunately she did not succeed. There did happen to be a very respectable gentleman who bore the same name. This gentleman had some friends of a humorous turn and they used to ring him up at all hours of the night, and make noises of animals at him down the telephone to remind him of his arrest in the zoo–quacking and growling and so on. He got cross; and he brought an action against the publishers, Messrs. Collins, for defamation of character. Well he lost, and I hope that this will be an earnest of saner decisions to come.

Find a Copy

- Find it at Amazon.com: People in Cages

- Find it at Amazon.co.uk: People in Cages

- Find it at AddAll.com: People in Cages

Every writer who’s ever been featured on

Every writer who’s ever been featured on  It was as an illustrator that King’s career finally took off. Throughout the 1920s, he was caught up in the convention-flounting wave of Mencken,

It was as an illustrator that King’s career finally took off. Throughout the 1920s, he was caught up in the convention-flounting wave of Mencken,  My theory is that King’s was a safe form of revolt. He mocked convention, but he didn’t exactly offer an alternative–nor did he suggest that people grab torches and set fire to police stations. He was like a

My theory is that King’s was a safe form of revolt. He mocked convention, but he didn’t exactly offer an alternative–nor did he suggest that people grab torches and set fire to police stations. He was like a