Flamingo

Flamingo is a spectacular failure. I kept thinking as I read of the time I saw a Titan III rocket blow up less than a thousand feet off the launchpad. No one would call that a success–but it sure was spectacular, awesome in its size and power, hitting us with a tremendous roar and shock wave seconds after we saw the explosion. Millions of dollars and the work of thousands was scattered in bits over the southern slopes of Vandenberg Air Force Base. A considerable effort lay behind that failure.

is a spectacular failure. I kept thinking as I read of the time I saw a Titan III rocket blow up less than a thousand feet off the launchpad. No one would call that a success–but it sure was spectacular, awesome in its size and power, hitting us with a tremendous roar and shock wave seconds after we saw the explosion. Millions of dollars and the work of thousands was scattered in bits over the southern slopes of Vandenberg Air Force Base. A considerable effort lay behind that failure.

I’m not clear exactly what Mary Borden was aiming at, but it certainly was high. The two novels that come to mind when looking for something to compare Flamingo to are The Bonfire of the Vanities

to are The Bonfire of the Vanities and Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead

and Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead –and no one could argue that either one of them lacked for ambition. Flamingo

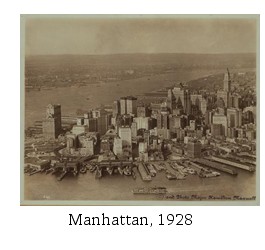

–and no one could argue that either one of them lacked for ambition. Flamingo is about the Old World colliding with the New World, about politics and money and art and power, about love, lust, jealousy, and ambition, and about Jazz Age New York City, with all its frenzy, noise, music, low lifes and skyscrapers. It has the potential to be a candidate for the Great American Novel.

is about the Old World colliding with the New World, about politics and money and art and power, about love, lust, jealousy, and ambition, and about Jazz Age New York City, with all its frenzy, noise, music, low lifes and skyscrapers. It has the potential to be a candidate for the Great American Novel.

Borden’s ambition led her to draft London and New York as characters:

London and New York had been talking all that summer. They had been trying to understand each other, but with very moderate success. They saw things differently, or perhaps New York didn’t try very hard to understand that old woman across the Atlantic, that old fogey.

Take a god-like view of things when she feels like it:

But, of course, in the star swarm that was traveling the heavens, this spinning of the earth through day and night was too rapid to be visible. An eye watching the stars splutter, fizzle, and go cold could not count the rotations of that little top. As for the building activity in New York, that would be less noticeable than the appearance of a slight feverish roughness, a tiny wart, on the side of the earth’s face.

Speak as the voice of fashion:

The Radio Building, Brown, Johnson & Campbell, Associated Architects, was the very latest thing in skyscrapers a year ago. It isn’t now. While I write, other buildings are going up that will put it in the shade, and there is a rumor that a rival firm is going to build just behind it a building that will make it look quite insignificant.

And even make her bold enough to admit her weaknesses to the reader:

From now on this story becomes very confused. It is going to be very difficult to keep track of these people once the Aquitania is tied up to the Cunard pier in the North River. It is going to be like a game of hide and seek, a sort of treasure hunt on switchbacks, in a crowd, in the dark, that jangles and jiggles, in a great confusion of noises, and it will be impossible to keep my eye on the clock and tell a straight narrative of how one thing happened after another.

To Borden’s credit, I have to say that I think Flamingo would have been far more effective if it had been 300-400 pages longer that it is. For what is great about it is Borden’s courage to do what Dickens and Zola and Tom and Thomas Wolfe did–to grab her narrative in her teeth and plunge with it into the depths of her subject, to force us to take time to really get to know someone, some place or some thing.

would have been far more effective if it had been 300-400 pages longer that it is. For what is great about it is Borden’s courage to do what Dickens and Zola and Tom and Thomas Wolfe did–to grab her narrative in her teeth and plunge with it into the depths of her subject, to force us to take time to really get to know someone, some place or some thing.

Here, for example, is the start of her sketch of a supporting player in the story. Ikey Daw is a Jewish financier, a deal-maker who would probably beat up Wolfe’s “Masters of the Universe” for their lunch money:

To Ikey Daw, who was equally at home in all the numerous Ritz Hotels of the earth, crossing the Atlantic was so much a matter of habit that he scarcely noticed whether he was stepping on or off a ship. His activities were much the same wherever he was. When the telephone was switched off, the wireless got busy, and the many threads that he spun from his fingers held taut, spreading out from him in a beautiful elastic web that covered the earth. He didn’t appear to be aware of the sea sliding and heaving beyond the rail of the Aquitania. It didn’t affect his appetite, and he didn’t look at it. Natural phenomena like storms, heat and cold, a lot of water, or dry land, and the things described in the geography books, never attracted his attention. Nor did the antics and idiosyncrasies of human beings, except for so far as they came into his scheme, and for the most part they didn’t. He could afford to despise them, and so, wherever he was, he was always in the same place, and although he traveled pretty constantly, he never seemed to himself to be moving and yet never had the feeling of being put. If he had any feeling of being somewhere, it was of being suspended in the air, like a spider at the center of his web, and the web, since he had spun it out of himself, revolved round him, contracting, twisting, and adjusting itself to cover the globe with himself continually at the middle of it.

Borden spends over dozen pages introducing us to Daw, telling about his rise to wealth and power, revealing his passions and foibles, taking us along as he walks along the deck of the ship, smugly dismissing the importance and concerns of the other passengers, hoping to corner Sir Victor in a conversation. It’s wonderfully descriptive and detailed stuff, and as a reader I was happy to plunge in along with Borden and swim through it regardless of where we might eventually surface.

Not there isn’t any action in Flamingo

Not there isn’t any action in Flamingo . There’s a storm at sea, an attempt to manipulate the stock market, an unsuccessful coup on a board of directors, parties, a fox-hunt, even a shooting in a nightclub. Most of the time things move along at a reasonable clip, aside from the dreadful passages about Peter Campbell’s saintly mother and holy fool brother upstate in simple, wholesome Campbelltown.

. There’s a storm at sea, an attempt to manipulate the stock market, an unsuccessful coup on a board of directors, parties, a fox-hunt, even a shooting in a nightclub. Most of the time things move along at a reasonable clip, aside from the dreadful passages about Peter Campbell’s saintly mother and holy fool brother upstate in simple, wholesome Campbelltown.

Unfortunately, Borden’s grand design is undermined by the weakness of its basic story. Peter Campbell, the boy genius of American architecture, has been in love with an Englishwoman he first met when they played together as children on a beach in Cornwall. He’s only seen her three times since, and even then, just in glances–across an opera house in Vienna, entering a car outside the Ritz in Paris. As Peter is about to launch his boldest project ever–a multi-block complex combining train station, corporate headquarters, stores, radio transmitters, and even a church–the woman arrives in New York.

She is Lady Frederika Joyce, wife to Sir Victor Joyce, who is coming to America to tell the President that Great Britain will not repay its war debts. As the Joyces step off the gangplank of the Acquitania (243 pages into a 418-page book), Peter hops on a train to Chicago to pitch a skyscraper for that city. Numerous things happen to both parties, but the net result is that Peter and Frederika do not meet face to face until page 379. Thirty-nine pages later, the book’s over. And no, they don’t run off together to live happily ever after. There are several sub-plots and a cast of dozens, but that’s it as far as the core story goes. And as a protagonist, Peter Campbell leaves a lot to be desired. Even Frederika muses at the end of the book, “He was a great artist but a weak little man ….”

To use an architectural analogy–since Borden devotes a lot of the reader’s time to Peter Campbell’s unique, inspiring designs and constructions–the flaw that topples Borden’s own grand design is the weakness of her foundation. It’s as if she slaps down a layer of tarmac and then proceeds to build the Empire State Building on top of it. For Flamingo to work, it either needed to be equipped with a rock-solid substantial foundation or to have everything that wasn’t essential slashed away in a ruthless fit of editing.

to work, it either needed to be equipped with a rock-solid substantial foundation or to have everything that wasn’t essential slashed away in a ruthless fit of editing.

Still, as failures go, this one is awe-inspiring and very much worthy of revival and reconsideration. Among her contemporaries, only John Dos Passos, in U. S. A. carried out a grander design. In neither case does the final product quite fulfill the promise of its initial chapters, but that in no way should suggest that either book is not interesting, as fascinating at times as a kaleidoscope.

carried out a grander design. In neither case does the final product quite fulfill the promise of its initial chapters, but that in no way should suggest that either book is not interesting, as fascinating at times as a kaleidoscope.

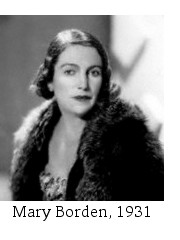

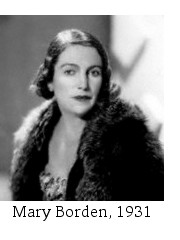

It’s particularly noteworthy when one realizes who Mary Borden was and what she was up to at the time she wrote Flamingo

It’s particularly noteworthy when one realizes who Mary Borden was and what she was up to at the time she wrote Flamingo . Borden was the daughter of a Chicago industrialist, who was married with two daughters and a third on the way and living in England when the First World War broke out. She used her money and influence to establish a field hospital and deployed with it to the Western Front, where she worked as a nurse throughout most of the war.

. Borden was the daughter of a Chicago industrialist, who was married with two daughters and a third on the way and living in England when the First World War broke out. She used her money and influence to establish a field hospital and deployed with it to the Western Front, where she worked as a nurse throughout most of the war.

During the war, she fell in love with Edward Spears, who played a key, if sometimes controversial, role as a liaison officer between the British and French armies. She divorced her first husband and married Spears just before the end of the war. After the war, they set up house in London. Spears went into business and Parliament. They both wrote memoirs of their experiences in the war: Borden’s The Forbidden Zone in 1929; Spears’ Liaison 1914

in 1929; Spears’ Liaison 1914 in 1930.

in 1930.

Somewhere between the war, divorce, marriage, and keeping up an active social life, Borden also found time to write novels, publishing her first book, The Romantic Woman , in 1920. Flamingo

, in 1920. Flamingo , 1927, was her fifth novel and sixth book. Before the end of the decade, her critical reputation had earned her a place alongside Edith Wharton and Ellen Glasgow in at least one survey of American women writers.

, 1927, was her fifth novel and sixth book. Before the end of the decade, her critical reputation had earned her a place alongside Edith Wharton and Ellen Glasgow in at least one survey of American women writers.

Though most of her family fortune was lost in the 1929 stock market crash, Borden continued her hectic pace, publishing seven more books before the Second World War broke out. Once again, she and Spears went to the front. Spears, now a general, served as Churchill’s military liaison with the French government during the desperate weeks in June 1940 when the Germans invaded. Borden, with the help of Lady Frances Hadfield, formed the British-French ambulance unit and went with it to support the French troops in the Alsace. She arranged the evacuation of the unit from France and then led it to Syria and Egypt, where they provided aid to Free French forces. Borden and the ambulance unit returned to France after DDay and took part in the grand liberation parade in Paris. However, Charles DeGaulle soon after disbanded it, reportedly in a pique, having issued a ban on British units participating in the parade.

Woe on he who takes on an industrious woman with a gift for the pen. Less than a year after the war, Borden published Journey Down a Blind Alley , which recounted the many ways in which DeGaulle and others in the Anglophobic Free French leadership went out of their ways to make things difficult, even as French soldiers were lying in the unit’s beds. (I picked up a copy of Journey

, which recounted the many ways in which DeGaulle and others in the Anglophobic Free French leadership went out of their ways to make things difficult, even as French soldiers were lying in the unit’s beds. (I picked up a copy of Journey some months ago in hopes of writing about it, but I found it no better than the average war memoir aside from the uniqueness of Borden and the unit’s circumstances.)

some months ago in hopes of writing about it, but I found it no better than the average war memoir aside from the uniqueness of Borden and the unit’s circumstances.)

Borden’s pace slowed only a bit after that. Her last book, The Hungry Leopard , was published in 1956 when she was 70. She died in 1968 and Spears passed six years later.

, was published in 1956 when she was 70. She died in 1968 and Spears passed six years later.

Locate a Copy

Flamingo, by Mary Borden

Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1927

I picked up Perdita, Get Lost

I picked up Perdita, Get Lost in the basement of the Montana Valley Book Store in little Alberton, Montana–one of the dwindling number of bookstores where you can plunge into stacks of books from more than a decade or two ago. I probably bought it as much for the fact that it’s a small gold-backed Pocket Book Cardinal Edition, which is up there with the little squarish Dell paperbacks from the early 1960s and the Yale Chronicles of Americas series among my favorite book formats.

is no timeless classic. The only thing going for it–which is about all any light comedy with legs can claim–is the writer’s style. In Alan R. Jackson’s case, he comes off quite the clever fellow, far more in the know about his characters than they could ever hope to be about themselves. But at least he manages a light touch through most of the book. Here, for example, he dissects a conversational misstep:

, a year or so before Perdita. From the title alone, I suspect it’s also a light comedy of life in early sixties Manhattan. I’ve no idea what became of him after publishing Perdita. While he’s no Wodehouse, he’s certainly of that ilk, if of a different continent and different decade, and I’ll probably give East 57th Street

a try one of these days. Marshmallows do have an occasional place in a well-rounded diet.

tells the story of a confrontation between whites and Native Americans to which neither journalism nor scholarship could possibly do justice. The novel takes place in South Dakota in the 1970s, when local developers start the short-lived Bones War while building a golf course on an ancient burial ground. The American Indian Movement is at its height, government authorities feel under constant siege, the U.S. appears on the verge of living up to its ideals or of falling flat on its face; Michael Doane uses this real-life civil strife to illuminate the individual troubles, and principles, such rebelliousness brings to the fore….

tells the story of a confrontation between whites and Native Americans to which neither journalism nor scholarship could possibly do justice. The novel takes place in South Dakota in the 1970s, when local developers start the short-lived Bones War while building a golf course on an ancient burial ground. The American Indian Movement is at its height, government authorities feel under constant siege, the U.S. appears on the verge of living up to its ideals or of falling flat on its face; Michael Doane uses this real-life civil strife to illuminate the individual troubles, and principles, such rebelliousness brings to the fore….  Thumbing through issues of

Thumbing through issues of  Possibly so; and it may be my fault that they don’t seem to notice there was no way for him to behave well. He had only a choice of behaving badly in different ways. What I mean is that like is like that. Many of the most admired moral examples really will not stand close and logical examination. It is so in the nature of things. Human beings are inevitably in an appalling predicament between their emotions and their obligations; the two elements are not even conveniently distinct, but inextricably snarled in a cat’s-cradle. And the more you try to untable it the worse it becomes.

Possibly so; and it may be my fault that they don’t seem to notice there was no way for him to behave well. He had only a choice of behaving badly in different ways. What I mean is that like is like that. Many of the most admired moral examples really will not stand close and logical examination. It is so in the nature of things. Human beings are inevitably in an appalling predicament between their emotions and their obligations; the two elements are not even conveniently distinct, but inextricably snarled in a cat’s-cradle. And the more you try to untable it the worse it becomes. He married twice. The first time, he was undecided between two sisters. His personal preference was for the younger and prettier of the two; one may assume he was in love with her. But out of sheer altruism, he felt it would be invidious to leave the elder and plainer sister slighted. So he married the elder. It is not known whether the younger was in love with him. She might have been. He was a man of charm, wit, and general attractiveness. And if the younger girl was in love with him, I can’t make up my mind–I am very fond of him–which of the two girls had the best right to murder him on the spot. Both of them, in my opinion, had every right to do so. He had injured the girl he loved and insulted the one he married.

He married twice. The first time, he was undecided between two sisters. His personal preference was for the younger and prettier of the two; one may assume he was in love with her. But out of sheer altruism, he felt it would be invidious to leave the elder and plainer sister slighted. So he married the elder. It is not known whether the younger was in love with him. She might have been. He was a man of charm, wit, and general attractiveness. And if the younger girl was in love with him, I can’t make up my mind–I am very fond of him–which of the two girls had the best right to murder him on the spot. Both of them, in my opinion, had every right to do so. He had injured the girl he loved and insulted the one he married.  Bruce Allen wrote recently to recommend the novels of François Mauriac:

Bruce Allen wrote recently to recommend the novels of François Mauriac: Fortunately for would-be readers, a good deal of Mauriac’s work is in print and easily available for purchase online. All of the above books are in print, as are several less-known works:

Fortunately for would-be readers, a good deal of Mauriac’s work is in print and easily available for purchase online. All of the above books are in print, as are several less-known works:

Not there isn’t any action in

Not there isn’t any action in  It’s particularly noteworthy when one realizes who

It’s particularly noteworthy when one realizes who  The story of Hungry Mind/Ruminator Books is a parable of how far a passion for books can take you … until simple economics kick in. David Unowsky, who founded his independent bookstore, Hungry Mind Books, near the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1970, and it acquired a reputation as one of a handful of truly great American bookstores. In the mid-1990s, he and his wife, Pearl Kilbride, along with other partners, started up an independent press, also known as Hungry Minds Books. Over the course of its nearly ten years’ existence, the press published 50 titles, with an emphasis on literary fiction, nonfiction and poetry, including a series of reissues of quality non-fiction under the rubrics of Hungry Mind Finds and Ruminator Finds.

The story of Hungry Mind/Ruminator Books is a parable of how far a passion for books can take you … until simple economics kick in. David Unowsky, who founded his independent bookstore, Hungry Mind Books, near the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1970, and it acquired a reputation as one of a handful of truly great American bookstores. In the mid-1990s, he and his wife, Pearl Kilbride, along with other partners, started up an independent press, also known as Hungry Minds Books. Over the course of its nearly ten years’ existence, the press published 50 titles, with an emphasis on literary fiction, nonfiction and poetry, including a series of reissues of quality non-fiction under the rubrics of Hungry Mind Finds and Ruminator Finds.

The writing is what makes

The writing is what makes  “In the summer of 1963 I bought a 1941 Lincoln limousine in New York, so that I might be chauffeur in California to the few remaining dignitaries in my family,” William Saroyan explains at the start of

“In the summer of 1963 I bought a 1941 Lincoln limousine in New York, so that I might be chauffeur in California to the few remaining dignitaries in my family,” William Saroyan explains at the start of