I have to admit that I rarely pick up a book without at least Googling its title, confirming that it’s out of print, and checking if it has at some time had something favorable written about it. Finding Carl Marzani’s The Survivor in a $1 book box outside a bookstore while getting my son settled at Drexel University last month, however, I bought it and then stuck it in my backpack for the flight back to Brussels without the usual due diligence.

One could argue that it’s best to approach a book with as little prior knowledge as possible, to prevent one’s perceptions from being contaminated by others’. After almost 50 years of reading, however, that’s almost impossible for me. Turning the first pages of The Survivor while sitting in the passenger lounge of the Philadelphia airport–and then through much of the seven hour flight home–was the closest I’ve come to an unadulterated encounter with a book in many years.

The Survivor starts strongly and I read the first hundred pages almost without a break. Marc Ferranti, a senior State Department official, has been asked to appear before a departmental hearing on his fitness for maintaining his security clearance. Although a veteran of the Official of Special Services (OSS)–the wartime pre-cursor to the Central Intelligence Agency–Ferranti had been an activist as a student in the 1930s. He left a Rhodes scholarship at Oxford to join the Abraham Lincoln Brigade fighting against Franco in the Spanish Civil War, and after his return to the U.S., he dabbled with membership in the Communist Party. Having sniffed out his radical connections, the department’s security officers want to make a showcase of Ferranti, anticipating President Truman’s decision to require Federal government employees to sign a loyalty oath.

The hearing is chaired by former Senator Richard Aldrich Bassett, a liberal Virginia Republican in his eighties. Much of the novel focuses on the meeting of minds between Bassett and Ferranti. Although a symbol of the American Establishment, Bassett had been strongly influenced by the Populist views of Tom Watson, a Populist politician from Georgia he ranks with Jefferson and Eugene V. Debs as the most important radicals in American history. An ally of FDR and recently-appointed Secretary of State George C. Marshall, Bassett is repulsed by the tactics of the Red-baiters now rising within the Truman administration and Congress. Through the efforts of his superior, an assistant secretary, Ferranti has learned that Bassett is, at least in principle, sympathetic to his case.

By far the strongest elements of The Survivor are the conversations and reflections of Bassett and Ferranti on the realities of politics and power in Washington:

“… You do not know much about the art of compromise, perhaps, but I do. Indeed I do. The Senate is the finest training ground for the art. You thunder no, and you murmur yes. Everyone saves face, always, everyone obtains a little of what he wants, alway. Compromise is the very soul of statemanship. The one time it failed in America we had a civil war, and the fault, in my judgment, lay squarely in the lack of a compromiser in the South, for the North had one of the greatest compromisers in our history: Mr. Lincoln.”

The Survivor takes place over the course of the three days of Ferranti’s hearing. The novel was Marzani’s first and only attempt at fiction, and one of the many ways in which this shows is the amount of activity he manages to shoe-horn into less than seventy-two hours.

Another is the awkward use of an manuscript Ferranti has written–a novel about his early years in America as an immigrant child. Ferranti believes he’s been singled out for persecution in an attempt by the Catholic Church to ally itself with reactionary forces within the Federal government, aided by his brother, a conservative Congressman. Ferranti manages to pass along the manuscript to Bassett, who then reads it in what appears to be one marathon evening. The passion and truth of Ferranti’s novel tugs at long-dormant radical allegiances within Bassett, and also evokes an empathy for the plight of foreigners learning to survive in America.

By this point, two hundred or so pages into The Survivor, my initial interest began to shift toward irritation. Through much of the middle of the book, Marzani tries to weave the narrative of Ferranti’s encounters between sessions of the hearing, the text of the manuscript, and Bassett’s reflections on Ferranti’s novel and life. It all becomes a rat’s nest I doubt anyone should ever bother to unravel.

In the end, Ferranti passes muster, keeping his job and opening up his chance to move on up the State Department ladder. Bassett is driven home to his Virginia estate, wondering if he hasn’t failed to live up to the radical ideals of his early mentor, Tom Watson: “The men and women his era has shunned and ridiculed might well turn out to be the precursors of a new life, a new country, perhaps a new civilization.” And this last line should give you a strong hint that The Survivor has a lot more in common with the works of Tom Clancy than those of Camus or even Koestler. It’s certainly not well-written or constructed, although I would say that it’s full of fine observations of bureaucratic manners.

Only after finishing The Survivor did I have a chance to research the book, and that’s when things became really interesting.

Carl Marzani, it turns out, bore more than a little resemble to his fictional counterpart, Marc Ferranti. Like Ferranti, he was born in Italy and emigrated with his family to the U.S. in his early teens. He excelled academically, earned a scholarship to Oxford, and left to fight in the Spanish Civil War with the Lincoln Brigade. He did not just dabble with Communism: he joined it outright and worked as an organizer in the late 1930s. After the U.S. entered the Second World War, he was recruited into the OSS and then moved over to the State Department.

As early as 1942, he was questioned by the FBI about his Communist Party membership. Feeling secure in the support of his OSS superiors and reluctant to give up his position, he lied. There were no immediate consequences.

In 1946, however, he was questioned again and determined to have perjured himself. In instructing Marzani’s jury, his judge said: “This court is not concerned with Communist vices. The issue is whether the defendant knowingly, willfully and feloniously made false statements to Government loyalty examiners.” Although he appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, his conviction was upheld and he served three years in prison. While in Federal prison, he wrote We Can Be Friends, a call to reserve the policies of the Truman Administration–influenced by George Kennan and others–to contain the Soviet Union’s expansions and maintain a relatively hostile diplomatic stance.

After being released from jail, Marzani worked as a professor of economics, a film producer, and co-owner of an independent publishing house, Marzani and Munsell. According to KGB archives, as detailed in The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB, Marzani was also a Soviet agent, operating under the code name of NORD. His firm owed at least some of its financial backing to the KGB, in return for publishing such sympathetic titles as Cuba vs. the C.I.A.

, which Marzani co-authored with Robert Light.

Marzani published The Survivor–before he began taking money from the KGB, it appears, but not long enough after the McCarthy era to have much chance of getting any recognition in the mainstream press. About the only magazine in the U.S. to take note of its publication was New World Review, the journal of the Friends of the Soviet Union. Although David Caute calls The Survivor

“the best and one of the most important novels” of the Cold War in his recent book, Politics and the Novel during the Cold War

, there appear to be few considerations of the book not colored by sympathy or distaste for Marzani’s own history.

Which leads one to wonder what Marzani intended to accomplish in writing it. Marzani may have been a victim of Red-baiting, but he doesn’t appear to have been an entirely innocent one, and The Survivor isn’t really an attempt to exonerate or justify himself. Although Marc Ferranti is portrayed as an exceptionally bright and shrewd operative, his actions are often more self-serving than heroic. If the book has any heroic figure, it’s Marc’s sister, Tessie, who shows herself ready to fight for both Party and family.

It could be that the novel was an experimental foray into autobiography. In the late 1980s, Marzani began writing a memoir titled The Education of a Reluctant Radical. It eventually spanned five volumes: Book 1: Roman Childhood; Book 2: Growing Up American

; Book 3: Spain, Munich and Dying Empires

; Book 4: From Pentagon to Penitentiary

; Book 5: Reconstruction

. The first volume, with an introduction by Italo Calvino, was published by the Topical Press in 1993, shortly before Marzani’s death in 1994. The last volume was not published until 2001, but is still available from Amazon.

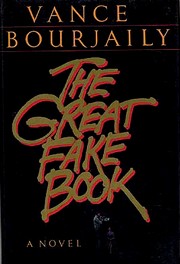

It pains me to start 2010 with two pans in a row, but few books have disappointed me as much as Vance Bourjaily’s little-known 1986 novel,

It pains me to start 2010 with two pans in a row, but few books have disappointed me as much as Vance Bourjaily’s little-known 1986 novel,

Although he began by calling the book “one of his [Bromfield’s] most remarkable achievements,” after devoting about four times as much text to a recap of the novel’s plot with only an occasional dig, Wilson then dismissed it as, “a small masterpiece of pointlessness and banality.”

Although he began by calling the book “one of his [Bromfield’s] most remarkable achievements,” after devoting about four times as much text to a recap of the novel’s plot with only an occasional dig, Wilson then dismissed it as, “a small masterpiece of pointlessness and banality.”

Fiction was not, I should note, Malcolm Ross’ forte. He spent most of his working life as a journalist and labor relations expert, serving as chairman of the Fair Employment Practice Committee through most of World War Two. His first book,

Fiction was not, I should note, Malcolm Ross’ forte. He spent most of his working life as a journalist and labor relations expert, serving as chairman of the Fair Employment Practice Committee through most of World War Two. His first book,  I was intrigued when I can across

I was intrigued when I can across  Every writer who’s ever been featured on

Every writer who’s ever been featured on  It was as an illustrator that King’s career finally took off. Throughout the 1920s, he was caught up in the convention-flounting wave of Mencken,

It was as an illustrator that King’s career finally took off. Throughout the 1920s, he was caught up in the convention-flounting wave of Mencken,  My theory is that King’s was a safe form of revolt. He mocked convention, but he didn’t exactly offer an alternative–nor did he suggest that people grab torches and set fire to police stations. He was like a

My theory is that King’s was a safe form of revolt. He mocked convention, but he didn’t exactly offer an alternative–nor did he suggest that people grab torches and set fire to police stations. He was like a  G. Wilson Knight subtitled this 1936 book “An Autobiographical Design,” and had he stuck to the autobiography and left the design out, I might have been less resentful about the several hours I devoted to assaulting its slopes. Perhaps I lack the mountaineering skills to attempt such a tower of intellect. But

G. Wilson Knight subtitled this 1936 book “An Autobiographical Design,” and had he stuck to the autobiography and left the design out, I might have been less resentful about the several hours I devoted to assaulting its slopes. Perhaps I lack the mountaineering skills to attempt such a tower of intellect. But

George Weller’s

George Weller’s