Excerpt

The entire horde, we saw with relief, was at home and sitting round the fire, which was, however, spitting, sizzling and crackling in a most extraordinary manner. Every now and then an aunt arose, stuck a green stick into the embers and drew it forth again with a chunk of burning material on the end.

“Why, that’s a shoulder of horse,” gasped Oswald.

“And that’s a loin of antelope,” I replied. We took the last mile at a run, and, with our mates hotfoot behind us, burst into the family circle.

“Welcome home, my dears,” shouted Father, starting up.

“Just in time for dinner,” cried Mother, and there were tears of joy on her dear, soot-streaked face. Then there was such a shouting, hugging, sniffing, embracing and laughing. “Clementina? Oswald is a lucky man!” “And who is Miss Bright Eyes? Griselda? Just what Ernest needs, my dear!” “Petronella? but her figure is superb–who’s have thought our Alexander could get a girl like that to look at him!” “And Honoria? Well, well, how nice–and what is this you have brought us? A lovely big rock? But how thoughtful of you, dear, to bring us anything,” and so on, until I made my voice heard.

“Mother! Why on earth are you using good meat for firewood?”

“Oh, Ernest, I quite forgot my joint in all the excitement; I’m afraid it will be dreadfully overdone–” and she hastily disengaged herself from the mêlée and pulled a great, smoking hunk of antelope from the fire.

“Oh, dear,” she said, inspecting it. “This side is burnt to cinders.”

“Never mind, my love,” said Father. “You know I like a bit of crackling. I’ll take the outside with pleasure.”

“But what are you talking about?” I implored them.

“Talking about? Cooking, of course!”

“What’s cooking?” I inquired patiently.

“The dinner,” said Father. “Oh, of course, now I come to think of it, your mother hadn’t invented it before you boys went away. Cooking, my sons, is–well–is a way of preparing game before you eat it; it’s an entirely novel method of reducing–er–ligaments and muscles to a more friable form for mastication–and–er–”

He frowned, and then a happy smile broke on his face. “But after all, why am I trying to explain it? The proof of the roast is in the eating. Just try some and see.”

My brothers and our mates were crowding round the strange, aromatic piece of meat which Mother now proffered to us. The girls who had already shied at the fire, backed timidly away; but Oswald boldly seized the joint, raised it to his muzzle, sank his teeth into it and tore away a piece. Immediately his face went crimson; he spluttered, choked, gasped, swallowed violently, dropped the joint (which Mother neatly caught) and writhed in agony; water ran out of his eyes and he madly pawed his mouth and throat.

“Oh, sorry, Oswald,” said Father. “Of course, you didn’t know. I ought to have mentioned it’s hot.”

Editor’s Comments

The Evolution Man is one of my favorite things in the world: a superbly well-crafted joke. A well-crafted joke wastes not a word, yet usually manages to encompass some fundamental flip of logic, twist of phrase, or shift of perspective, such as:

Two atoms are walking along when one cries out, “I’ve lost an electron!”

The other atom asks, “Are you sure?”

“Yes, I’m positive.”

In The Evolution Man, Roy Lewis tells the story of “the greatest ape-man of the Pleistocene era”–at least, in the view of his family. Now, when most novelists approach the problem of writing a modern novel set in prehistory, they quickly have to confront a rather ugly practical fact: how do you write about something that took place before there was such a thing as writing? And how on Earth do you write dialogue when, as far as we know, it was all a matter of grunts and shrieks?

The default answer seems to be to create some crude subset of modern English loosely related to what the Indians speak in Hollywood westerns: “Antelope run from great noise. White man carry big fire stick.”

Lewis dispensed with such artificial devices. To him, the tale of prehistoric man could only be told in his own tongue. The fact that it turned out to be purest Oxbridge English was simply a lucky accident:

We were often hard put to it to keep up the supply of fuel for a big fire, even though a good edge on quartzite will cut through a four-inch bough of cedar in ten minutes; it was the elephants and mammoths who kept us warm with their thoughtful habit of tearing up trees to test the strength of their tusks and trunks. Elephas antiquus was even more given to this than is the modern type, for he was still hard at it evolving, and there is nothing that an evolving animal worries about more than how his teeth are getting along.

That prehistoric man also grasped concepts such as the measurement of time and distance, the classification of species, and evolution also goes a long way towards eliminating many of the discomfiting aspects of having to understand the situation of beings related to us through only genetics and deeply-buried instinctive psychology.

Thus, instead of fumbling around at several removes from the characters, we are blessed with an eloquent and perceptive narrator–Ernest. A likable chap just on the cusp of manhood, Ernest is one of a band of ape-men and -women struggling to survive near the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro in the days when “the great ice-cap was still advancing.”

Ernest’s father, Edward, is the head of the band, and it is Edward’s ambitions that fuel the central conflict of the novel. Edward and his brother, Vanya, carry on a running argument: “Each went his own way, firmly convinced that the other was tragically mistaken about the direction in which the anthropoid species was evolving….”

The argument escalates suddenly when Vanya drops out of the trees to confront Edward’s latest discovery: fire.

“You’ve done it now, Edward,” he rumbled. “I might have gueesed this would happen sooner or later, but I suppose I thought there was a limit even to your folly. But of course I was wrong! I’ve only got to turn my back on you for an hour and I find you up to some freshy idiocy. And now this! Edward, if ever I warned you before, if ever I begged you, as your elder brother, to think again before you continued on your catastrophic course, to amend your life before it involved you and yours in irretrievable disaster, let me say now, with tenfold emphasis: Stop!”

Edward himself is skeptical of Vanya’s premonitions: “I mean, is this really the turning point? I thought it might be, but it’s hard to be quite sure. Certainly a turning point in the ascent of man, but is it the?”

For Vanya, however, fire is the first step down a slippery slope that can only lead to mass destruction: “This could end anywhere. It affects everybody. Even me. You might burn down the forest with it.”

Control of technology, it turns out, has been an issue for quite some time. Fire proves a lovely innovation, enabling the family to wrest a cozy cave from a band of bears, but it takes quite some effort at first. Each time the fire goes out, Edward has to hike up to the top of the nearest volcano to light a new torch and convey the flame, stage by stage, back to the cave.

The family is happy to enjoy the comfort and safety of the cave and fire, but Edward is ever restless. He sees only one direction in which to move: forward. He is ever mindful of the evolutionary imperative:

“The secret of modern industry lies in the intelligent utilization of by-products,” he would remark frowning, and then in a bound he would seize some infant crawling on all fours, smack it savagely, stand it upright, and upbraid my sisters: “When will you realize that at two they should be toddlers? I tell you we must train out this instinctual tendency to revert to quadrupedal locomotion. Unless that is lost all is lost! Our hands, our brains, everything! We started walking upright back in the Miocene, and if you think I am going to tolerate the destruction of millions of years of progress by a parcel of idle wenches, you are mistaken. Keep that child on his hind legs, miss, or I’ll take a stick to your behind, see if I don’t.”

This zeal for progress eventually leads Edward to gather his older sons, including Oswald, and lead them away from the cave. After a trek of many days, he brings them to a halt, announcing to the boys, “It is time you found mates and started families of your own for the sake of the species; and that is why I have brought you here. Not twenty miles to the south there is another horde…”

The boys protest: “People always mate with their sisters,” one cries. “It’s the done thing.”

“Not any more,” responds Edward. “Exogamy begins right here.”

Edward sets his sons in search of mates, at the threat of a run-through with his trusty spear. Off they head, each chasing an ape-girl over hill and dale, until they encounter “one of the very greatest discoveries of the Middle Pleistocene”: love.

Cheerfully mated, the brothers head back to the camp with their women, and in the scene excerpted above, find the family yet further evolved through the invention of cooking. Eating cooked meat brings unexpected benefits, including healthier teeth, better digestion–and leisure.

The family masters group hunting, and celebrates its new members with a great feast of elephant, antelope, and bison, sauced with berries, blood, and aepyornis eggs. Edward rises to offer an after-dinner speech brimming with hubris: “To every other species we cry: Beware! Either you shall be our slaves or you shall disappear from the surface of the earth. We will be master here; we will outfight, outthink, outmanoeuvre, outpropagate and outevolve you! That is our policy and there is no other.”

“Yes there is,” Vanya retorts. “Back to the trees.”

As ever, pride goeth before the fall. A few days later, Edward and one of his sons discover the magical combination of flint and lodestone. They make their own fire, and run back to the family bursting with pride: “We’ve done it! Hurrah! Hurrah! We’ve done it!”

Unfortunately, Edward lacks the foresight to envision the cautions of Smokey the Bear. Vanya’s direst predictions come true, and the family finds itself on a forced migration in search of new hunting grounds. Perfectly wonderful new grounds it does eventually find, but these, inconveniently, already have occupants. This leads to the dilemma: to share the secret of fire or not?

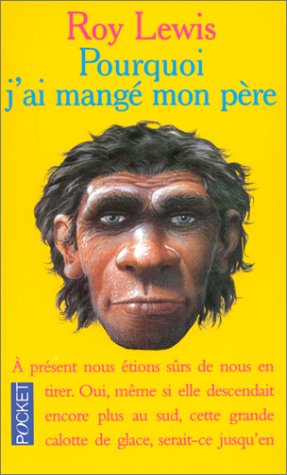

Edward the booster’s reaction can be expected, but how the family resolves the dilemma is not. And therein lies the great twist in this joke. Progress, it turns out, is not inevitable. (I would leave it at that, but the title of the French translation of The Evolution Man telegraphs the punchline: Pourquoi j’ai mangé mon père).

Despite his hand in Edward’s demise, Ernest does note, with respect, “that in his passing he helped to shape the basic social institutions of parricide and patriphagy which give continuity both to the community and to the individual.”

Plato’s parable of the cave may predate The Evolution Man by a few thousand years–but Roy Lewis’ version is inifinitely funnier.

Note: The Evolution Man was recommended on Crooked Timber’s “A different book list.”

Other Comments

- · Review of The Evolution Man by novelist David Louis Edelman:

- While Roy Lewis’s The Evolution Man is filled with Cro-Magnon humor, the book has much more simmering in its prehistoric pot than gags about stone tablet typewriters. Beneath its mammoth-skin covering, the book wrestles with the very idea of technology and how far humanity should take it, from the point of view of a culture where turning back to all fours was a tangible possibility.

- · Terry Pratchett on The Evolution Man, from “Close Encounters: Eminent writers, editors and critics choose some favorite works of fantasy and science fiction”, The Washington Post, Sunday, 7 April 2002:

- I first read The Evolution Man by Roy Lewis (in and out of print all the time — a Web search is advised!) in 1960. It contains no starships, no robots, no computers, none of the things that some mainstream critics think sf is about — but it is the hardest of hard-core science fiction, the very essence. It’s also the funniest book I have ever read, and it showed me what could be done. It concerns a few hectic years in the life of a family of Pleistocene humanoids. They’ve learned to walk upright and now they’re ready for the big stuff — fire, cookery, music, arts and the remarkable discovery that you shouldn’t mate with your sister. Because it’s too easy, says Father, the visionary horde leader. You can’t get a head of water without damming the stream. In order to progress humanity must create inhibitions, frustrations and complexes, and drive itself out of an animal Eden. To rise, we must screw ourselves up. Nonsense, says his apelike brother Uncle Vanya. Get back to the trees, it’ll all end in tears! And so the debate rages under the prehistoric sky until, one day, someone invents the bow and arrow. . . . And we know what happened next. The debate continues. But never has it been put so well as in this insightful book.

Find Out More

Locate a Copy

The Evolution Man, by Roy Lewis

London: Penguin Books, 1963

First published as What We Did to Father

London: Hutchinson, 1960

Also published as Once Upon an Ice Age

London: Terra Nova Books, 1979

There’s a limit to this respect, though. In fact, we find that horses may have formed a bit too much of Amos’ perspective:

There’s a limit to this respect, though. In fact, we find that horses may have formed a bit too much of Amos’ perspective: